The Path in Heaven

It was nearly 90 years ago that a certain Fritz Bonsens (alias Alfred Hillebrandt), in a pamphlet entitled, Die Götter des Ṛgveda: Eine euhemeristische Skizze,1 attacked the method of explaining the mythology of the Veda by "nature mythology," a method advocated by Müller, Roth, Kuhn, Bergaigne, Bloomfield and Hillebrandt. Bonsens begins by saying:

Once Indra was a great king, just as there still are kings today in India…

and he ends with:

…The Ṛgveda knows nothing of natural phenomena that have become gods, it knows only of human beings.2

Since the time of Bonsens, scholars have developed other methods for interpreting Vedic mythology,3 most notably the structural method. Yet, I think that the importance of night sky phenomena in Vedic mythology has not been sufficiently appreciated—although F. B. J. Kuiper is a notable exception here.4 In the following pages I will try to describe some aspects of Vedic mythology, and I hope that this will result neither in a "euhemeristic sketch," nor in a new "nature mythology."5

I

We know that the sky is the domain of the Vedic gods and that men hope to go to heaven (for a well-defined period).6 Heaven is called dyáuḥ. The day-time sky is illuminated by the sun (sū́rya-), which is also called svàr "light, sun" or svargá- loká- "the shining world," as it is usually translated. It is well known that the Ṛgvedic Indians attached great importance to certain major phenomena of the sky:7 the rising of the sun, preceded by the dawn (uṣás), the progress of the moon through the constellations (nákṣatra-), and also to the progress of the months and the seasons (ṛtú-) of the year. The importance of the first appearance of the dawn of the New Year has also been studied,8 but it is less well known that the Indo-Iranians and the (Ṛg)vedic Aryans observed many other phenomena of the day-time sky and the night sky, for example the daily rising (and setting) of the sun during the year.9

It is impossible to speak here of all the problems posed by the movements of the sun and the moon, of the solstices (the viṣūvat), and of the observations that one made regarding the sun during the noon hour, at sunrise and at sunset.10 I would like to focus here on another aspect of the night sky: that of the movement of the stars in general (well described by the hymn RV 1.105)11 and, in particular, that of the Milky Way.12

While dyáuḥ represents the bright day-time sky and also that of the night sky (according to RV 1.105.10, cf. n. 9 and Kirfel, Kosmographie, p. 34), the sense of svár is ambiguous. This word can mean "sun," and "illuminated sky" as well as "the brilliant paradise (of the gods)" at the firmament (nā́ka) of the sky. In the same way, svargá- (loká) means the paradise (of light).13 The connotation of light/brilliance of these words is contained in their roots *dieu-, *sh2uel(g)-, but the expression svargá- loká- which literally means "shining world, shining space," in fact means—when one reviews the Vedic passages—the Milky Way.14

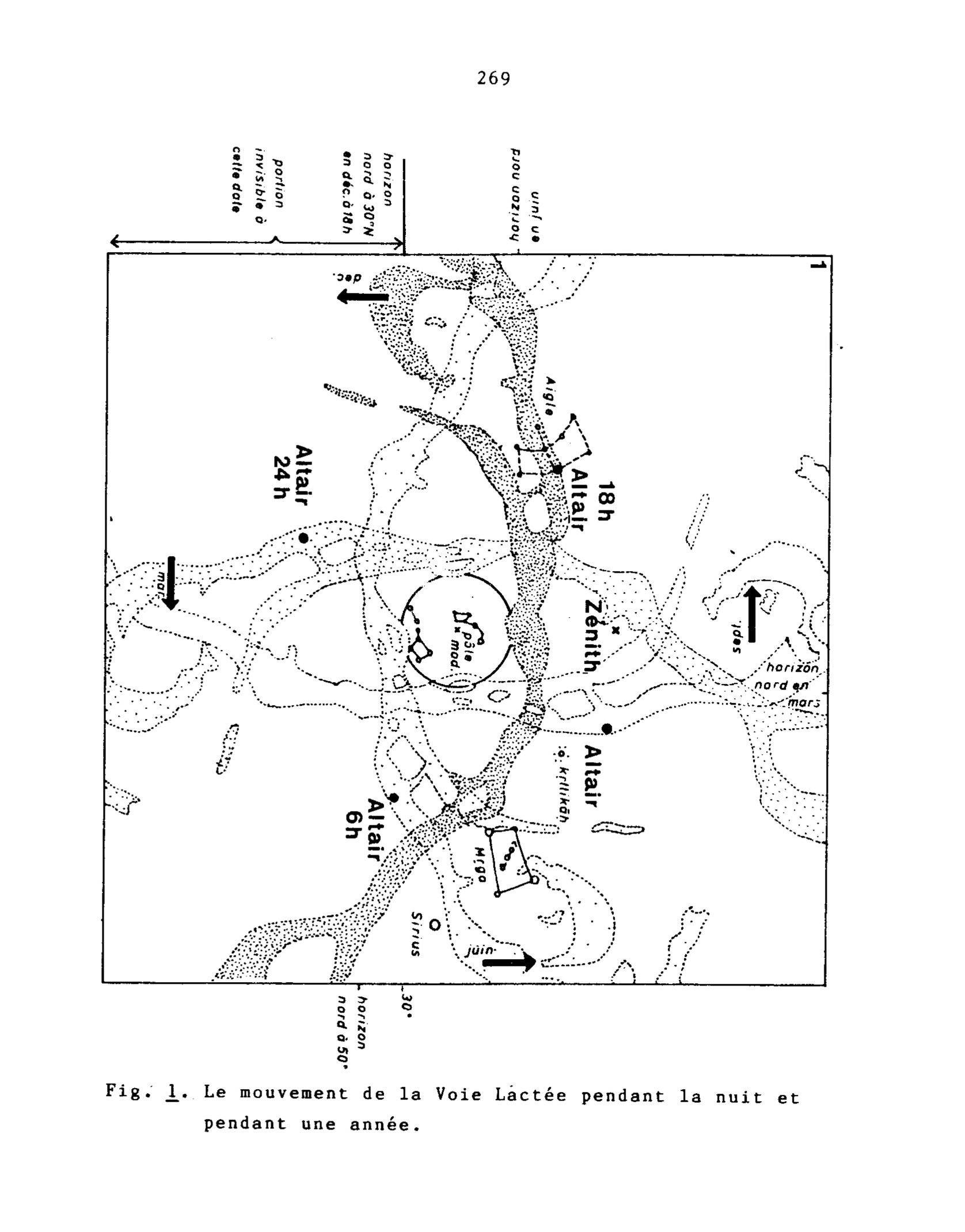

The Milky Way "moves towards the east"15 or "a little bit towards the east and towards the north."16 That means, unlike the sun and the moon, it moves apasalaví (in the counter-clockwise direction), as one can observe for one of its stars during the course of the year.

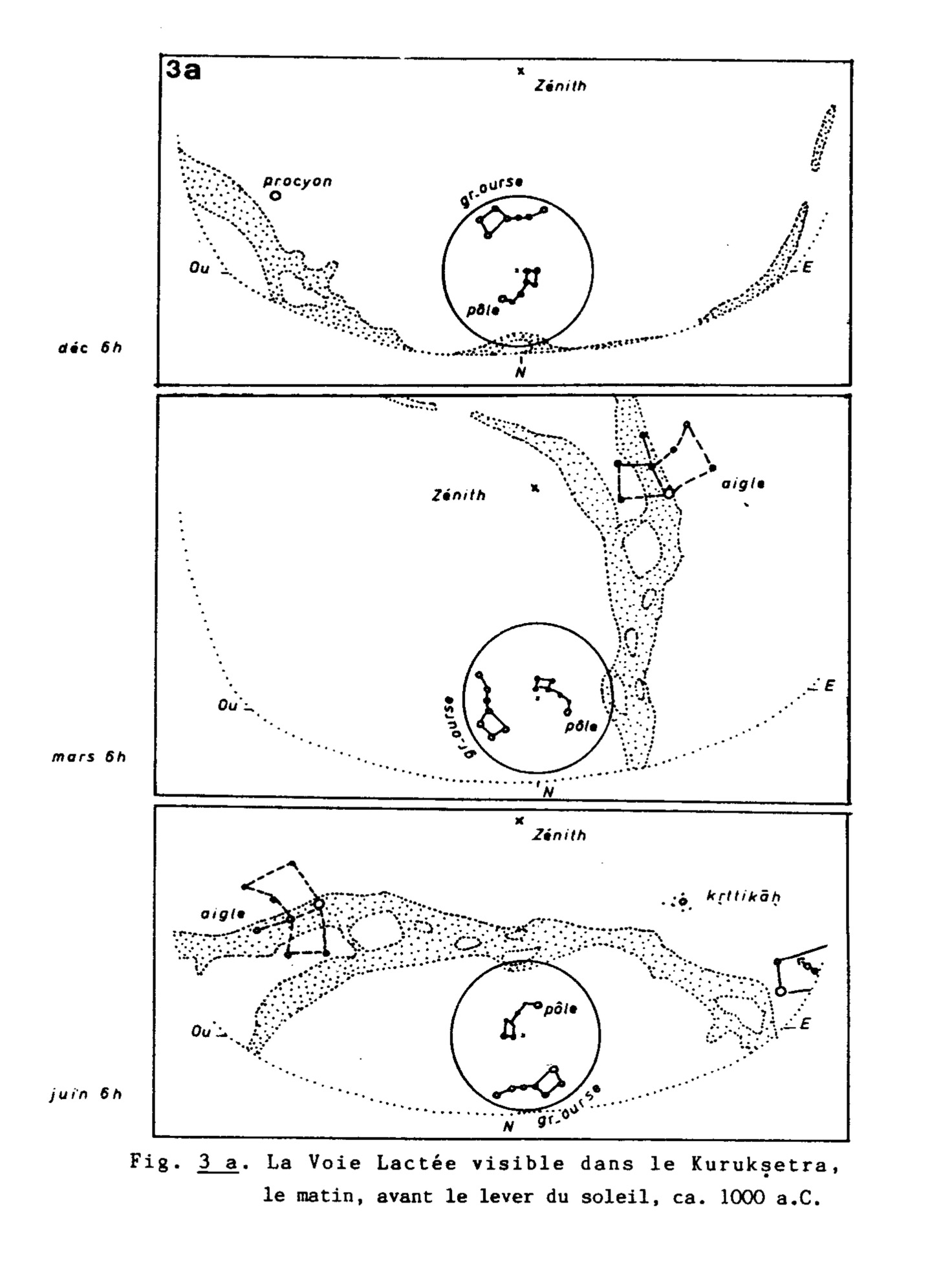

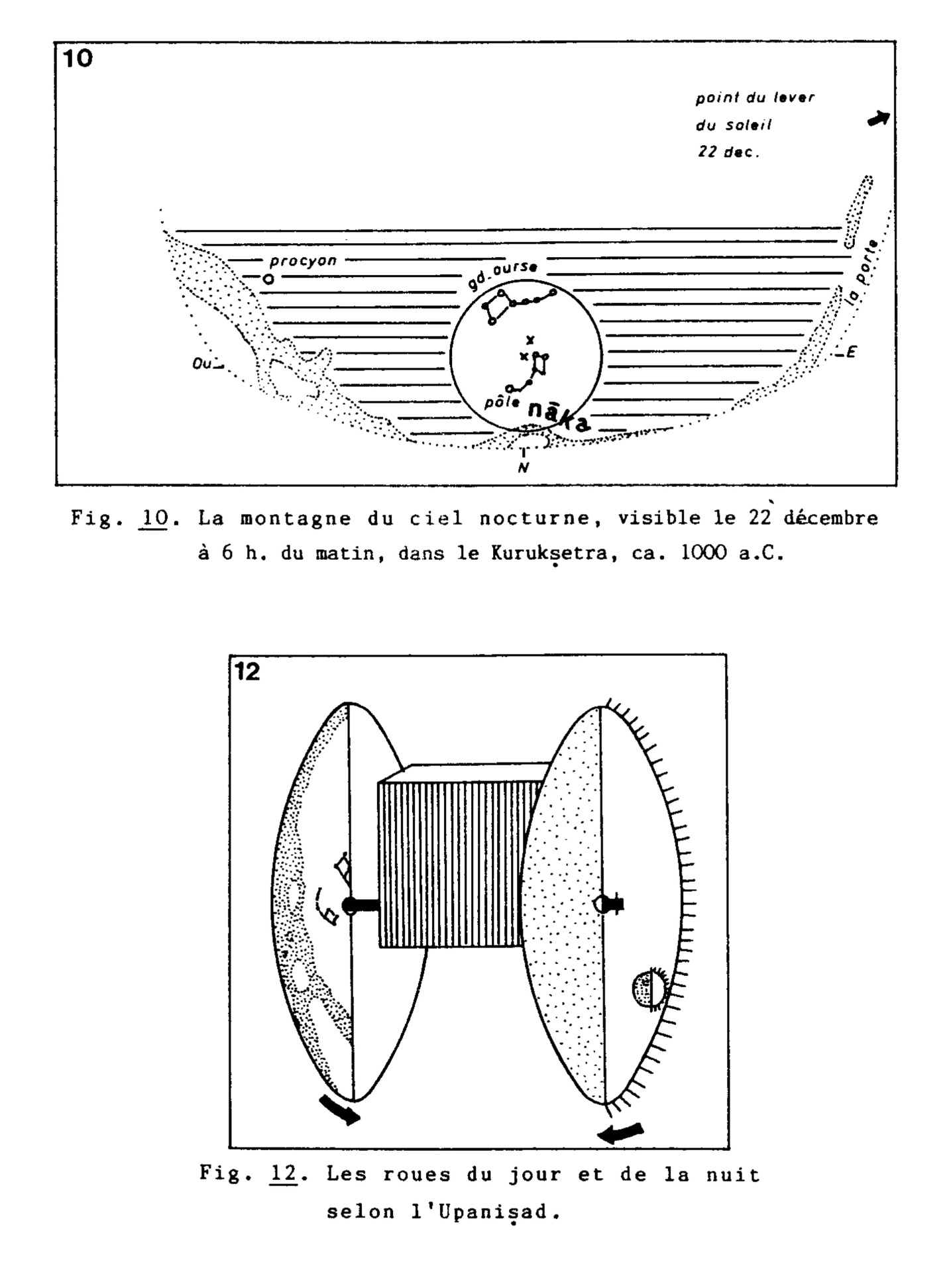

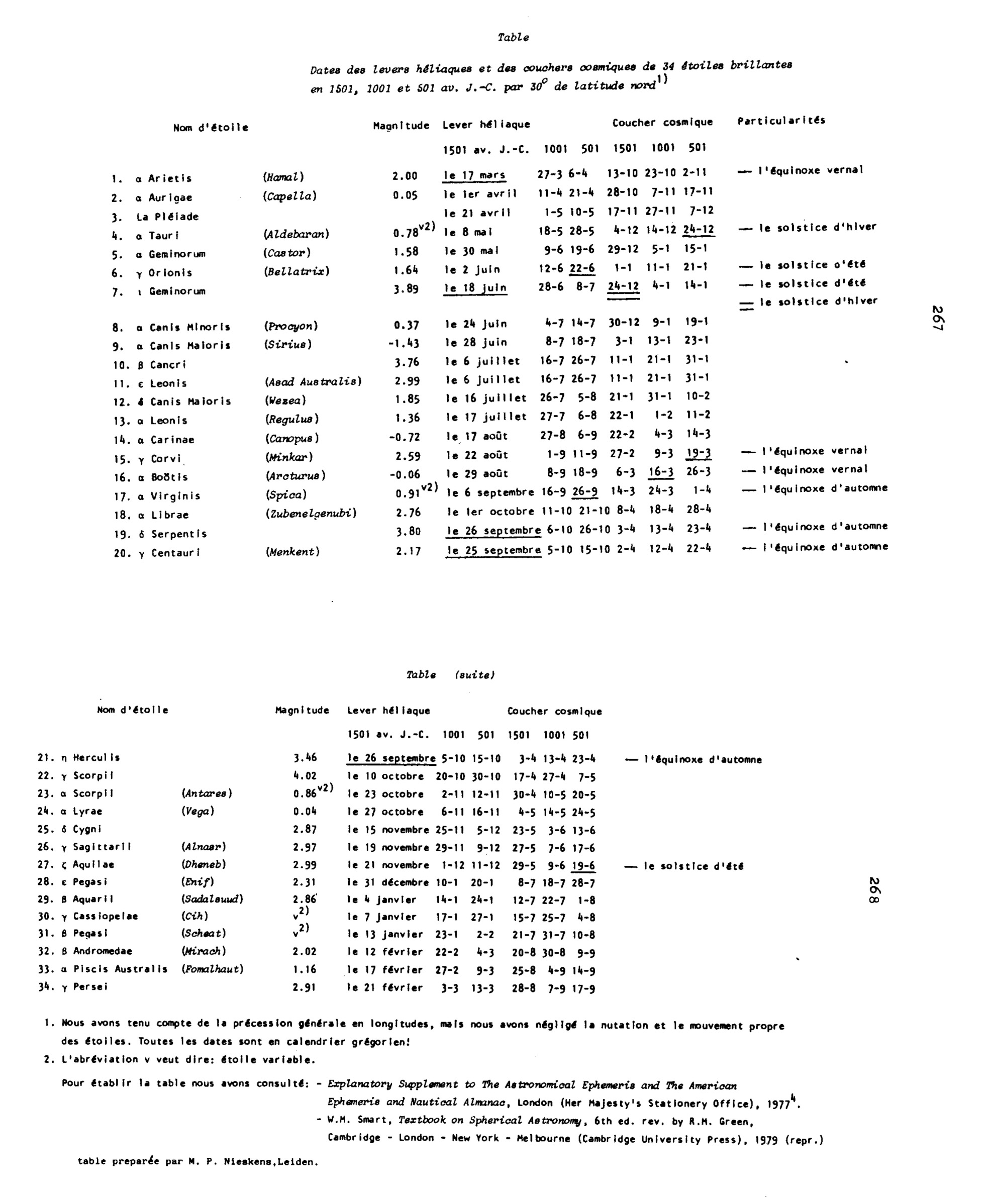

It is generally said that the svar-, the heavens, is "situated above" (the earth and the intermediate space); one thinks obviously of the sky during the day (RV 7.60.3, etc.) and of the nocturnal heaven (the dyáuḥ) when one observes the stars and the moon.17 This heaven as a "height," its position at the very top of the sky, is furthermore attested above the Pole of the sky, an axis around which the Big Dipper turns, which is visible in the latitude of India during only a part of the year.18 The data that I present here are calculated for the Vedic period (ca. 1500–1000 BCE).19

The svargá- loká-, the Milky Way, moves in this "up above" position. One can read in the Jaiminīya Brāhmaṇa (JB 2.298 paragraph 156): pratīpam iva vai svargo lokaḥ "partially against the flow, the luminous world (moves)." Even more clear are the parallel texts: TS 7.5.7.4, JB 1.85, PB 6.7.10, KS 33.7 pratikūlám iva hītás svargó lokáḥ "in fact, from this point, the luminous world (becomes moves) partially against the flow," i.e. from the initial moment of gavām ayana, of the winter solstice.20 The counter-current movement is opposite to that of the sun. Similarly, a given star "sinks" below the pole, and then goes up, against the flow, towards the pole.21

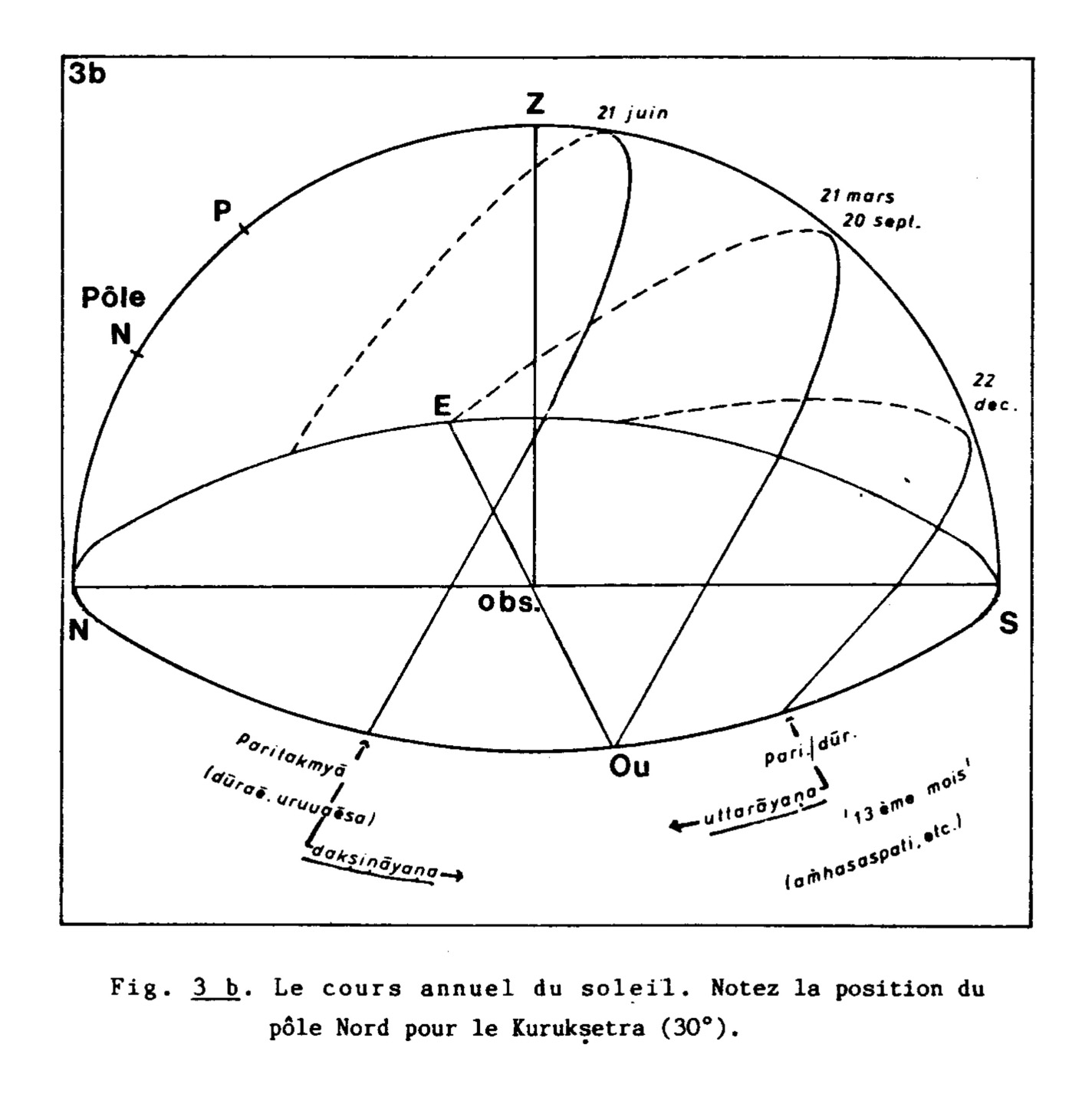

The sun must receive the aid of ritual during the period when it marches northwards (uttarāyaṇa, see Figure 3b.) Just as the agnihotra daily ensures the sunrise, the gavām ayana ensures the passage of two critical moments: the winter and summer solstices, on mahāvrata and viṣūvat days.22 The Milky Way is continuous (saṃtata-): JB 1.85 saṃtata iva vai svargo lokaḥ "In truth the shining world is almost continuous." It forms a cord (tantu-).23 The relationship of the tantu cord with the sacrificial ground is evident, already in AV 12.2.38 = PS 17.31.8

úpāstarīr ákaro lokám etám

urúḥ prathatām ásamaḥ svargáḥ

tásmiṃ chrayātai mahiṣáḥ suparṇó

devā́ enam devátābhyaḥ práyacchān

"You have strewn (the ceremonial straw: barhis), you have created this world; may the shining (world), without equal, stretch widely! On this (world) will alight the majestic eagle. May the gods offer it to the deities."24

The Milky Way is identified here with the straw, which stretches between the terrestrial world (the gārhapatya fire), the celestial world (āhavanīya) and the lunar world (dakṣināgni).25 These examples26 suffice to demonstrate that there is a Vedic notion of the Milky Way, a notion that has up to now been almost ignored.27

II

The svargá- loká- "shining world, Milky Way" is practically absent in the Ṛgveda: the first occurrences appear in the Atharvaveda, Śaunaka and Paippalāda. In the RV, svargá- is attested only once, in an addition to the hymn of Purūravas and Urvaśī: 10.95.18 svargá u tvám api mādayase "You also, you will rejoice in the shining (world)."28 What, then, does the RV call the Milky Way?

It is remarkable that mythologists have not recognized29 this phenomenon, which is very much visible in the Indian sky in autumn, winter and springtime (but sometimes also during the monsoon). I think that the Ṛgvedic name for the Milky Way is Sarasvatī, etymologically "the possessor of many ponds." It is a suitable designation.30 Like many other peoples the Indian see a river in this celestial phenomenon; such is also the case in post-Vedic literature, where svar-nadī and svargaṅgā "celestial Ganga" are two common names for it.31

If we consider the Vedic passages where Sarasvatī is mentioned, we will quickly see that she is a terrestrial river,32 a goddess governing the fecundity of women,33 but also that she is the object of descriptions which are considerably less banal. She descends from the mountains (from the Himālayas) but equally from the "high heavens:" RV 5.43.11 á no divó bṛhatáḥ parvatā́d ā́, sárasvatī yajatā́ gantu yajñám "May, from the high heavens, from the mountain, Sarasvatī, worthy of sacrifice, come to our sacrifice!" One may recall here that, according to F. B. J. Kuiper, the rock, the mountain is the primordial mount which, turned round and inverted during the night, is situated in the nocturnal sky.34

The proximity of the goddess Rā́kā, who helps in the formation of the embryo and in childbirth, indicates that Sarasvatī cannot be merely a river: RV 5.42.12 vŕṣṇaḥ pátnīr nadyàḥ … | sárasvatī bṛhaddivótá rākā́, daśasyántīr varivasyatu śubhrā́ḥ "May the rivers, the wives of the bull... Sarasvatī of the high heavens and Rākā, splendid ones, be agreeable and cause us to succeed!" RV hymn 6.61 is clearer (cf. verses 1, 3, 5, 6, 14); one can see that the idea of a goddess is crossed with that of a river "with wheels of gold" (híraṇyavartani, verse 7): "She has filled the terrestrial (spaces) and the broad intermediate space" (āpaprúṣī pā́rthivány urú rájo antárikṣam, verse 11). In verse 12 we have, more clearly: triṣadhásthā saptádhātuḥ, pañca jātā́ vardháyantī "She has three stays, she is made up of seven elements (tributaries? -- RV 10.75), she increases the five peoples." Coming from the sky, she thus crosses the aerial space and runs over the earth with her seven sisters (the rivers of the Panjab).

One can see clearly from all of this that Sarasvatī is more than a simple terrestrial river. This is also the place to cite a famous passage from the AV 6.89.3, which should be compared with RV 7.36.6. One will read there:

aháṃ mitráṃ varuṇáṃ

aháṃ ha devī́ sárasvatī

máhyaṃ tvā mádhyaṃ bhū́myā, ubhā́v ántau sám asyatām

"Towards you, for me Mitra and Varuṇa, for me the goddess Sarasvatī, for me the center of the earth—may they throw together the two confines (of the earth / of the Sarasvatī)."

We shall see that Sarasvatī, the Milky Way, appears one time at the center, another time at the confines of the earth (at the horizon): at these points, the Milky Way seems to touch the earth during the night (for several hours, if need be), see Figures 1 and 4.

III

Let us put aside for a moment the Milky Way, and consider several aspects of the Vedic concept of paradise—in the heavens or in the land of the god Yama.

It is well known35 that the life of those who have attained the heavens is very agreeable (RV 9.113): with a perfect body, to which even limbs lost in battle have been restored, the pitṛ are seated beneath a tree (aśvattha, supalāśa) with shadowing leaves and drink madhu (AV 5.4.3, 18.4.3) or play at dice (VādhB.).36 This paradise is situated in the sky, which has three37 levels: ŚB 9.2.3.26 "From the earth, I shall rise to the aerial space, from the aerial space to the sky (dívam), from the sky, from the back of the firmament (divó, nā́kasya pṛṣṭhā́t) to the light (svàr, jóytir agām)." It is situated above the Big Dipper (RV 10.82.2. Paradise is identical with the palace of the king Yama, but it can be distinct from that of the gods.38

IV

How is it possible to ascend to paradise? Even the gods were not there at the beginning of the world. They attained the heavens by ascending to them through ritual;39 the Asuras and the Sādhyas wanted to do likewise, but they failed (see TS 7.2.1.3). The Brahmans and the Kṣatriyas are expected to do the same. However, the means of reaching the heavens are numerous: sacrifice, ascetic austerities (tapas) in all their forms, the ritual at full moon and new moon, knowledge, mystical formulas (brahman-), the knowledge of the saṃvatsara (the year). More important are the special sacrifice offered in the spring and at the two solstices, and the long-term sacrifices, the sattra.40 The Brāhmaṇa texts provide very diverse lists of these means of accession to the heavens.41

Among these rituals one can rise to "the shining world," "paradise" by means of the following activities:42 one climbs the axis that leads to the gods;43 one employs the symbols of the rotating (heavens) for example in a ritual which employs a "swing;"44 the rituals called sattra (long-term ritual) and the yātsattra (ritual "pilgrimage") are particularly important.45

Through these "sessions" one hopes to obtain livestock, wealth, children: the common desires of the Veda; however, the sattras have the peculiar feature of not ceasing until their objective (utthāna, udṛc, tīrtha) has been achieved. For example, the objective will not be achieved unless 100 cows become a thousand, "because that world there (the heavens, asau lokaḥ) is worth a thousand" (TS 7.2.4; or equally: "is located at a height of a thousand cows").46 Even if one achieves this goal, one does not stay away, especially if it is a matter of the celestial world: TS 7.3.10.3-4 yád imáṃ lokáṃ ná pratyavaróheyur úd vā mā́dyeyur yájamānaḥ prá vā mīyeran "If they did not came back down into our world, the sacrificers would go mad or would perish."47 Among the sattras certain are characterised as "pilgrimages along the Sarasvatī;" these are the yātsattra.48

V

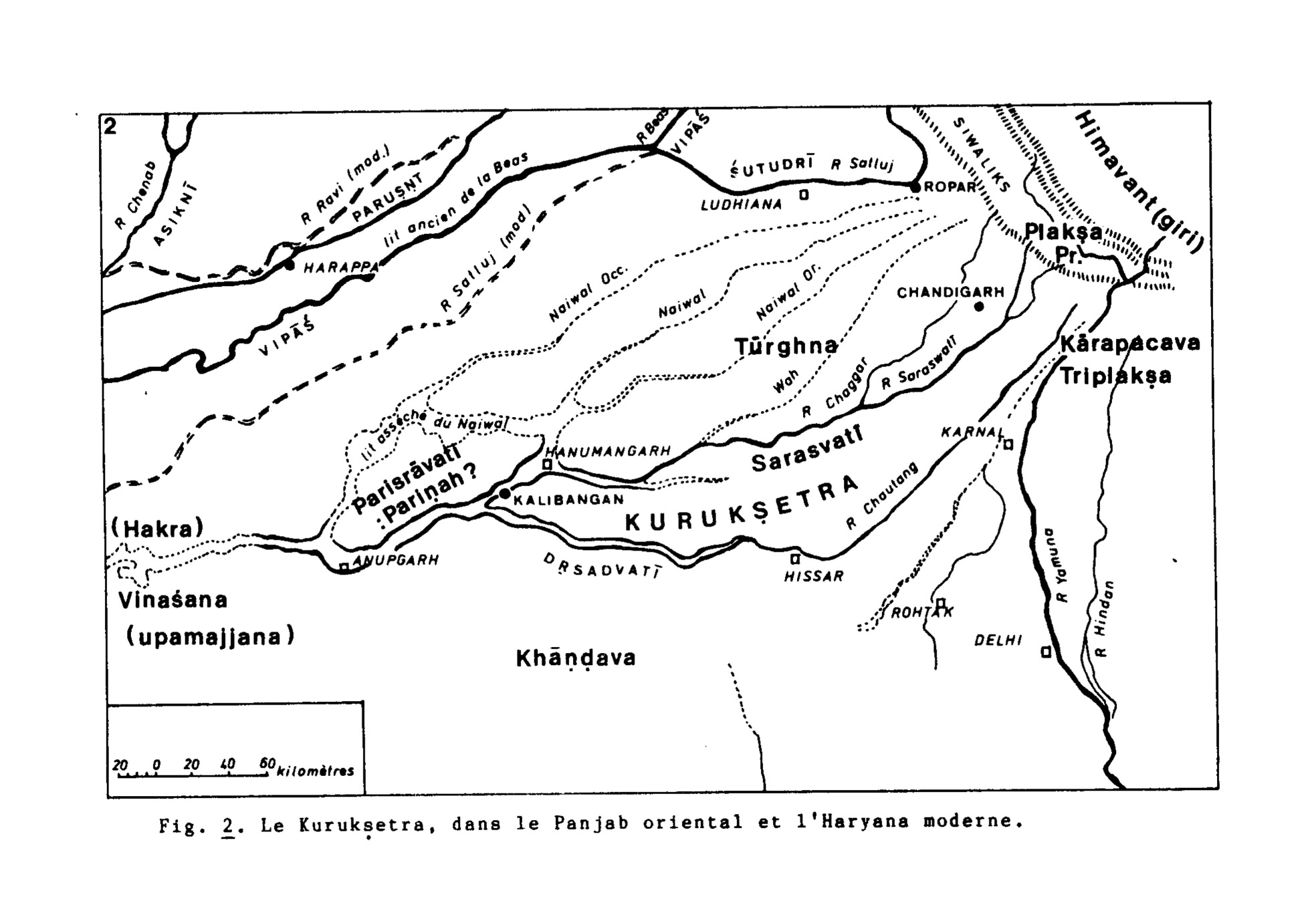

Today, the Sarsuti is a river to the east of the Panjab, situated to the northwest of Delhi and often called Ghaggar in our atlases. In the Vedic period it must have been a considerably more important river, as we are led to assume by the arid bed that skirts the Indus as far as the Rann of Kacch: the Nārā and the Hakra.49 The modern Sarsuti and Chautang—the Vedic Sarasvatī and Dṛṣadvatī—form the borders of the Kurukṣetra, a toponomy that one encounters neither in the Ṛgveda nor the AV. But in the time of the YV (MS, KS and TS) Saṃhitās, Kurukṣetra (see Figure 2) is the sacred territory: devayajanam—the sacrificial ground of the gods.50 It is also the battlefield of the Mahābhārata.

Let us read one of the texts that describe the sattra on the banks of the Sarasvatī (and of the Dṛṣadvatī, cf. paragraph VIII below): JB II 297 (paragraph 156) sqq:51

The consecration [dīkṣā] is performed at the place where the Sarasvatī disappears [into the desert sands]. They proceed with the consecration on the southern shore [of the Sarasvatī]... Each day they go as far as they have been able to throw the śamyā [the yoke-pin]. These throws of the śamyā constitute genuine strides towards the shining world.52

In JB 2.298 one can read that every day, during these rituals, they make progress from the southwest to the northeast, then to the north, in the direction of the current of the Sarasvatī, arriving finally at the "source" (or at the "escape," at the "Plakṣa Prāsravaṇa"), passing from the southern shore to the northern shore of the river. In total they cover the distance that the arrow of a Niṣāda can cover (= approximately 150 metres). Following the sacrifice one performs the avabhṛtha, a final bath, with the waters which flow from the source of the river (in the Himālayas). Very often the yātsattra leads to death: the Keśin Darbhya "disappeared" at the Plakṣa Prāsravaṇa (JB 2.299 paragraph 157). One should in fact "achieve" one's goal—the reward of the ritual, whether it is paradise or a thousand cows,53 or in order to be cured of an illness54—because that is where one becomes invisible (adṛśya PB 12.9.4) and it is from there that no one returns, as the many examples contained in the Jaiminīya Brāhmaṇa show, where the texts speak of a ritual "without return" (anavasarga-).55 This is not surprising, because this is the "stairway" that goes towards the shining world (PB 12.9.2 eṣo va etad dveḥ sopānam yad dīkṣā "This, in truth, the entrance [dīkṣā] is the stairway of the sky").

This "stairway to the heavens" that leads to paradise, the svargá-loká-, seems in fact to be more than a pious wish of the sacrificers. It is based in reality. The spatial situation of this pilgrimage is, I believe, very significant: one begins the ritual when the Sarasvatī disappears into the desert, at a distance of approximately 200 kilometres to the west of Delhi, and one goes in the direction of the source—located far away in the Himālayas—there where the Yamunā also escapes from the mountains. The Brahmaṇa texts often indicate that one must perform the sacrifice at Sarasvatī, if that is not possible, at Dṛṣadvatī, if not there, at the confluence of the two, if not there, at the Sindhu (the Indus, in the Panjab), if not there, at the Gaṅgā and finally, at Yamunā.56 There is a gradual slide from the northwest of India to the east. That is why, at the end of the pilgrimage, one carries out a bath in the pure water which springs from the Himālayas in the northeast.57 This bath is also one of the elements necessary to reach the heavens (see JB 2.302 paragraph 158, RV 10.136.5 = PS 5.38 áśvāsaḥ pavitré abhí ṣūdátaḥ ... apó diviyā́ḥ "the (horses) who are washed at the point of purification... divine waters" = "the waters from the heavens," of Yamunā and Sarasvatī).58 One can see that the pilgrimage is not only a ritual act: the particular space covered on the earth is at the same time a reflection, a symbol of the heavenly journey, of the cosmic journey of the soul of the dead. Here is a remarkable parallel to what one can observe in Nubian texts where the dead follow the path from the south to the north along the heavenly Nile.59

Thus, these pilgrimages consist of an earthly action (vyūha-) which has a reflection, a counterpart in the sky (pratimā).60 The sattras61 and ritual in general allow for the creation of a different cosmos, a "second world," a "world created by action" (kṛtaloka- see AB 4.6) in heaven.62

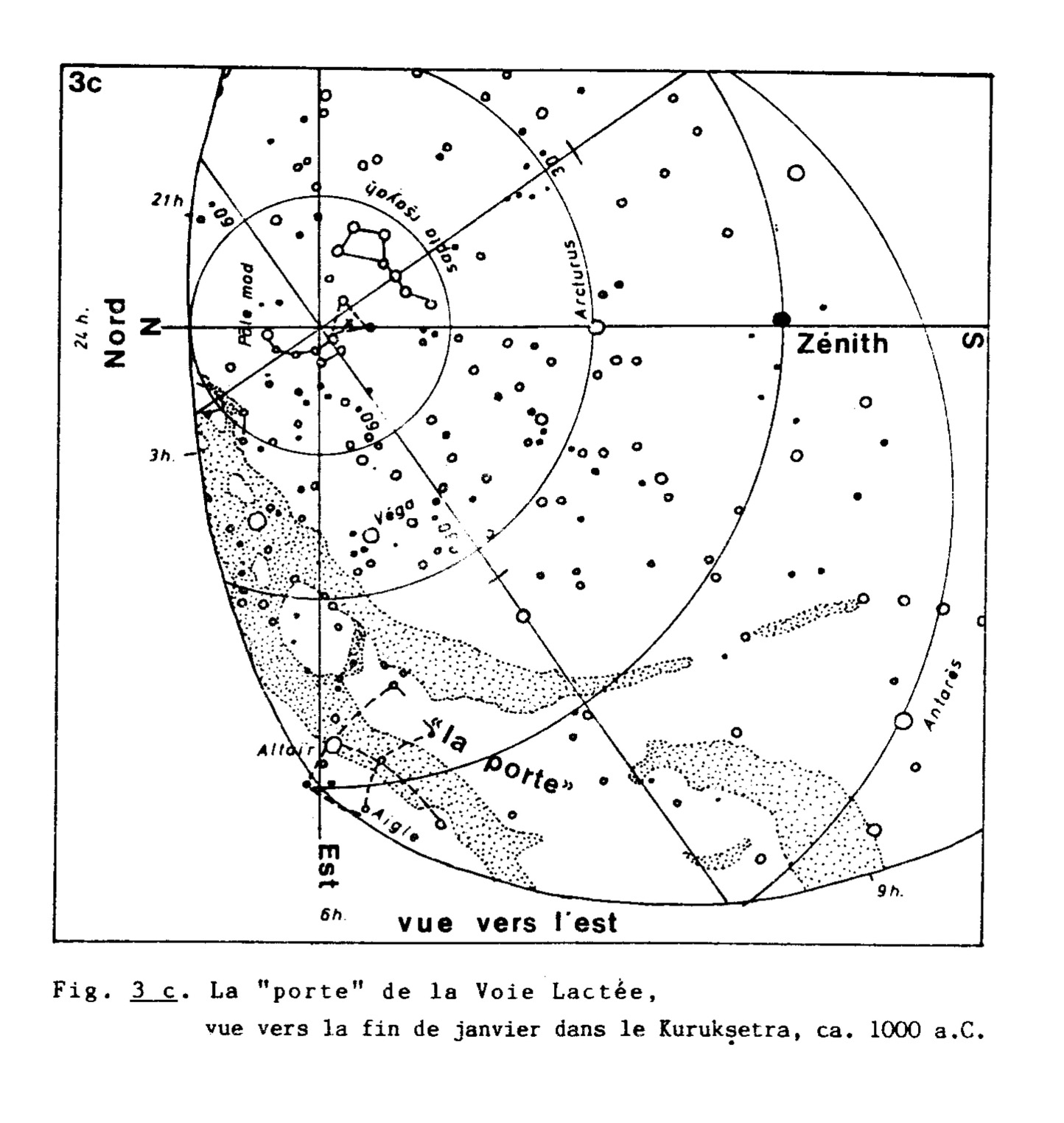

This reflection of the earthly situation in the cosmos becomes clear, if we consider the Yamunā and the Sarasvatī as terrestrial reflections of the two arms of the Milky Way—an interpretation that I shall attempt to prove.63 Since the ritual begins in the place where the Sarasvatī disappears into the sands of the Rājasthan desert, and since it ends in a "final bath" at the origin of the Sarasvatī, at the source itself, the Plakṣa Prāsravaṇa—in such a way that the sacrI sacrificers climb "from one step of the staircase to the other"—one will see easily that the Sarasvatī and Yamunā rivers become the Milky Way, the "shining world," the "heavens."64 In this ritual one goes therefore to the final point (where Sarasvatī vanishes into the sands) along the southern shore of the river, progressing each day a few dozen metres to the east,65 and then to the north (towards the Himālayas and the source of the Sarasvatī).66 Since the ritual begins in winter,67 the progression corresponds to the movement of the western tip of the Milky Way (near to the Aquila constellation), which shifts daily, a bit above the pole, rising slowly from the east towards the south, then from there descending to disappear finally in the west in the month of July. This tip of the Milky Way will not reappear in the morning until December, before sunrise; at the winter solstice, one of the two branches of this eastern part of the Milky Way is distinctly visible (see Figure 3a).

In the morning—an important moment to begin the sacrifice—when the stars are still visible, one turns to the east, for example to perform the agnihotra sacrifice which is intended to cause the sun to rise. In winter68 one can observe at this moment a characteristic phenomenon: in the east, near the constellation that in our astronomy is called Aquila, the Milky Way divides into two branches (two streams) which form the "doorway to the heavens"69 as described in the ŚB. In the ritual, one turns towards the northeast, because "in this direction one finds the doorway to the heavens" (ŚB 6.6.2.4), (see Figure 3c). This doorway appears before sunrise during the several weeks that precede the winter solstice.70 In passing by this "doorway" and rising towards the east and the north along the length of the Sarasvatī—the terrestrial reflection of the Milky Way—one rises also along the Milky Way, a new portion of which becomes visible in the east and northeast each morning. One goes against the current of the Sarasvatī—and also "against the current" of the Milky Way—since the latter is in the morning at its highest point, almost the zenith, in May and June, before falling again towards the southeast, the south and the southwest in autumn (when the "doorway" is no longer visible in the morning).

The ascent is therefore the path of the gods, and the descent that of the manes, the "fathers," the devayāna and the pitṛyāna.71 During its ascension the Milky Way requires the gavām ayana ritual,72 in the course of which the sacrificers use this movement to "go to the heavens." The ending point of this sacrificial pilgrimage is the Plakṣa Prāsravaṇa tree, the source of the Sarasvatī as the name itself implies. This tree is at the same time the center of the world73 and of the heavens, the axis mundi, in the JUB (4.26.12: plakṣasya prāsravaṇasya pradeśamātrād udak tat pṛthivyai madhyam) and the VādhPiS (divo madhyam).74

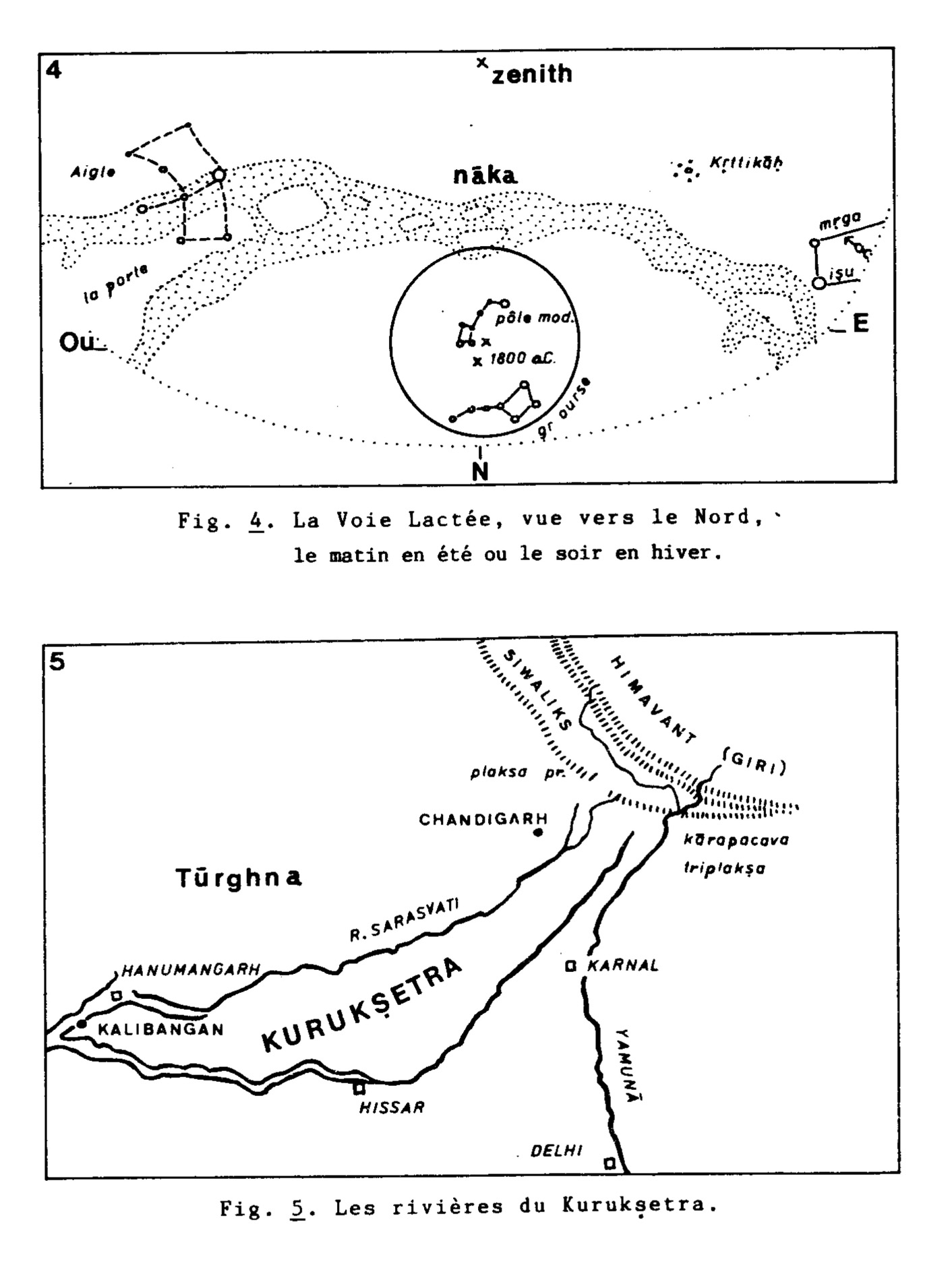

In fact, the final bath—the end of the sacrifice—takes place in the Yamunā, which lies to the east of the Plakṣa Prāsravaṇa. It is at this point, in summer, that one sees to the north in the morning, the Milky Way, which crowns the eastern edge of the sky (see Figure 4).

Another terrestrial reflection of this celestial situation: the Sarasvatī75 and the Yamunā76 come "from on high," from the Himālayas, and flow to the west and to the east respectively (see Figure 5). Through the Yamunā, which corresponds to the "eastern branch" of the Milky Way, one returns to the earth.77 It is necessary to travel by this river if one does not wish to remain in the heavens, at the zenith, or to disappear with the movement of the Milky Way below the horizon, to the southwest, then to the southeast, into the region of the pitṛs.78

VI

If these observations are correct there are several conclusions to be drawn from them, with ramifications of varying importance to Indian and Indo-Iranian cosmology.

a) Pilgrimage and suicide

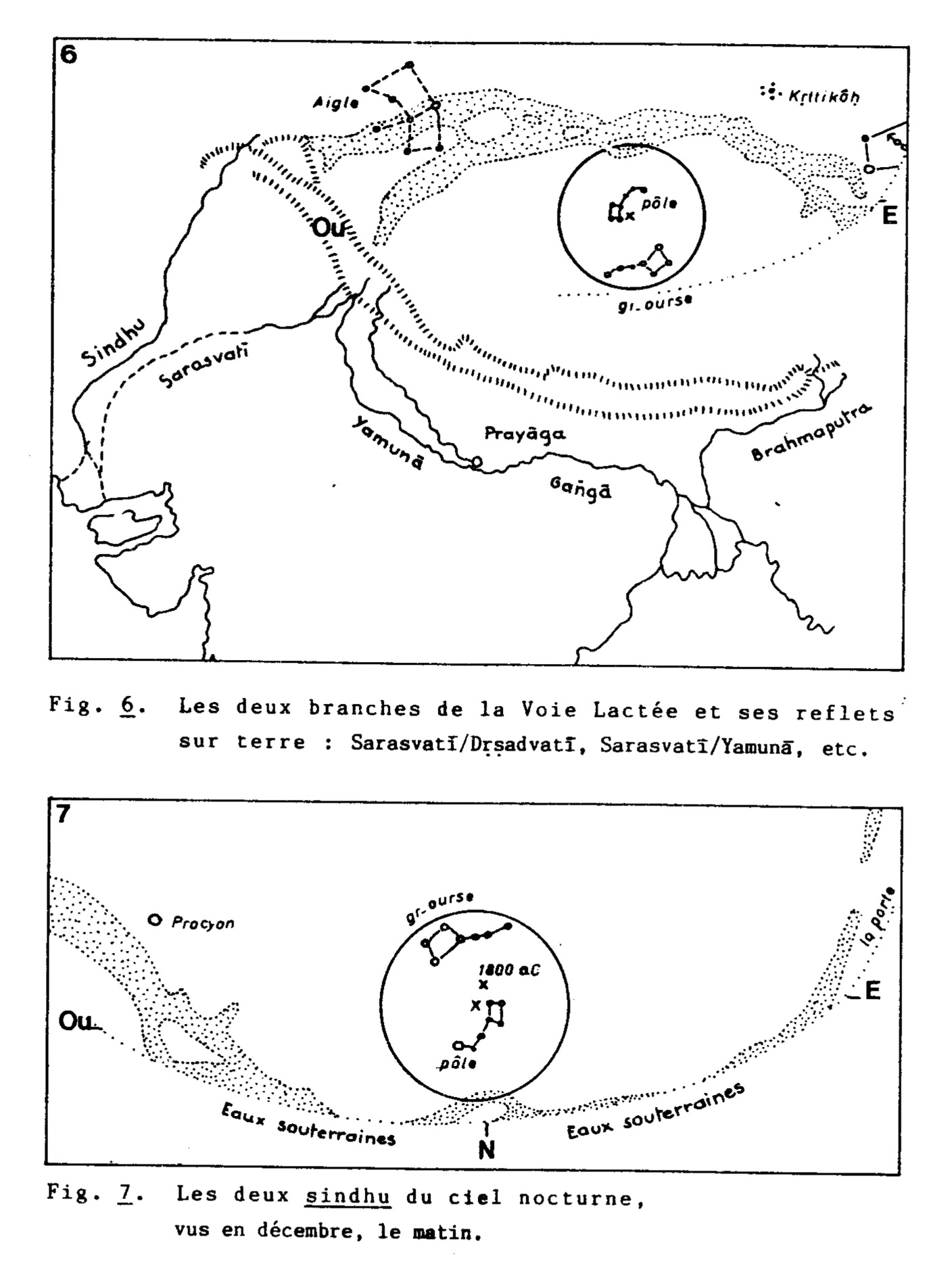

We have uncovered the first pilgrimage along a sacred river, in this case, it is the most holy of rivers. Later, in the Mahābhārata, there will be many sacred tīrthas on the shores of the Sarasvatī and other rivers.79 One spot sacred to all is that of the triveṇī at Prayāga/ Allahabad, where the Yamunā, the Ganges, and the celestial river merge invisibly. As we know, the Ganges falls from the heavens onto the head of Śiva and, from a celestial river (svarṇadī, etc.), is transformed into a terrestrial stream.80 We have already seen that the Yamunā is the "shining world," the "heavens," "paradise." The Milky Way—as it is seen each night—falls from the heavens onto the earth in one or in two rivers, for example on December evenings (see Figure 6).

In the northern part of India a similar scenario can be reconstructed for the Yamunā, the Ganges (and also the Brahmaputra?). Prayāga interests us for another reason: it is, in fact, at the confluence of the Yamunā and the Ganges that one commits suicide by hurling oneself into the river from the top of a tree. By performing this act at this place one attains paradise immediately.81 All of this is reminiscent of the pilgrimage, the yātsattra, on the shores of the Sarasvatī: as from the top of the Triplakṣa tree alongside the Yamunā, it is at the Plakṣa Prāsravaṇa that one attains one's objective or that one becomes "invisible" to the eyes of humans, as is said in the PB.82 The Prayāga then represents the "invisible descent" of the celestial river, the Milky Way, which from the sky becomes a terrestrial river, visible to all: the Yamunā and the Ganges. One comes back from heaven—in symbolic form —by descending from the "invisible tree" (the axis mundi) into the waters of the river. This movement is exactly parallel to the path of the soul into the world of rebirth: a descent from heaven along the Milky Way (and the Yamunā), as has been already mentioned, cf. n. 47 and 71.83

Going further in this direction, we arrive at a large number of questions concerning the "geography" and the nomenclature of the waters of heaven and their links to the terrestrial rivers.84 This question has not yet been satisfactorily resolved, but it is clear that the ancient Indians, as well as the ancient Iranians, had a very precise idea of the movement and of the position of the Milky Way.85 These observations are confirmed by a number of Iranian facts, where we find once again several of the elements that we discussed above:86 the Milky Way is the celestial river Raŋhā (= Rasā́).

b) Av. Vourukaša and həṇdu

The "defective" material of the Avesta contains several passages which reflect a cosmological system similar to that of the Veda. To the "shining world" of the Indians (svarga- loka-, Sarasvatī) corresponds the "lake"—or, better, the "sheet of water"—of the zraiiah- Vourukaša- "the one who possesses wide bays," just as the Sarasvatī has many ponds.84 The Vourukaša is described as "shining" (bāmi-).85 Just as the Plakṣa is situated at the center of the earth and of the sky, a vīspó.biš- ("all-healing")86 tree marks the center of the zraiiah Vourukaša. An eagle (or falcon)87 dwells there: "The divine eagle remains in the world without equal," as says the AV (cf. footnote 24 above). The eagle is called Sarasvat in the RV: 1.164.52 divyám suparṇáṃ vāyasám bṛhántam, apā́m gárbham darśatám óṣadhīnām…sárasvantam "The divine eagle, the superior bird, the embryo of the waters and of the plants, pleasant to look at, .... Sarasvat."88 The river that falls from the heavens and the mountains to the earth is, as in the Vedas, a river and a goddess: Arəduuī Sūrā Anāhitā "the prospering one, brave, immaculate,"89 who grants children as does Sarasvatī. Sometimes this river is called the Raŋhā (Ved. Rāsa) and once the Vaŋvhī (Ved. *Vasvī), which is conflated with the ocean encircling the world. The Vedic Rasā is described fairly clearly in RV 10.108 and JB 2.440. In the RV, the dog Saramā, sent by the gods to seek out the cows of the Paṇis, runs to the end of the world, to the points of inflexion, that is to say to the "critical points" (paritakmyā)90 near the waters of the Rasā; leaping over the Rasā, she sketches the edges of the heavens (pári divó ántān ... pátantī, verse 5). In the JB, the hiding place of the Paṇis lies on an island of the Rasā: the island formed by the two rivers of the Milky Way, which do not separate except in the Aquila constellation. The JB says: eṣā ha vai sā Rasā yaiṣārvāk samudrasya vāpāyatī (+vār āyatī)91 "It is the (well known) Rasā that, turned at this point, goes towards the water of the ocean." Like the Avestan Raŋhā, the Rasā comes from the (celestial) samudra towards us (arvāk), towards the terrestrial world.92 It is interesting to note here that the gods, before sending Saramā, had first sent an eagle, who, in the Milky Way, brings to mind the eagle of the AV.

The ocean, the river at the edges of the world, is also called the Vourukaša, but it is never referred to as Sarasvatī in Vedic, only as samudra (and Rasā).93 In Avestan one still finds the eastern and western həṇdu (Y. 57.29: ušastaire hənduuō… daošastaire), which are not the sapta sindhu of the Veda (or the hapta həṇdu of V. 1.18). Y.10.104 is sufficiently clear: Mitra seizes the liar on the western həṇdu and on the eastern həṇdu,94 at the mouth of the Raŋhā, at the center of the world, which corresponds to the Atharvavedic terminology (6.89.3: mádhyam bhúmyā ubhā́v ántau).

We can thus posit a quasi-identification of the Vedic and Avestan concepts of the nocturnal heavens and the celestial rivers.95

c) The xvarənah-

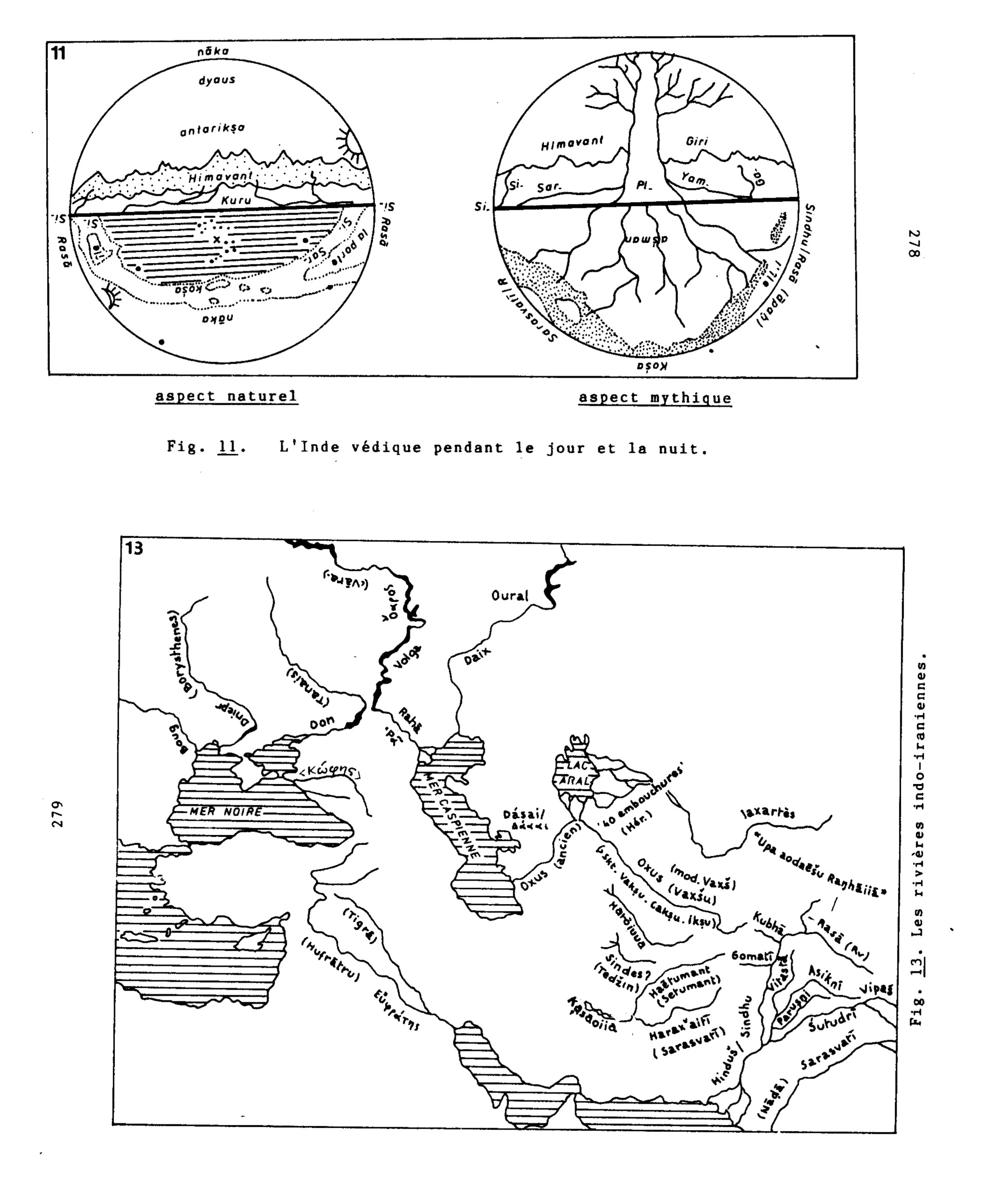

These considerations are not without relevance to another extremely interesting problem in Iranian mythology: that of the xvarənah- "majesty (of kings)," "glory," that sits upon kings and sometimes goes to hide in the Vourukaša river ("lake"). In Vedic, the corresponding word, which would be *svarṇas, does not exist; we do, however, find svàrṇara- in a half dozen passages. This word denotes a pond, or the source of Soma, situated in the firmament (as Lüders has already remarked).96 According to Kuiper,97 this is the kośa ("barrel") at the nocturnal solstice, which is tipped by Varuṇa to make water fall, including the water of the rains. I think that this overwhelming glow represented by xvarənah- is situated at the zenith, and that during the night it appears above the northernmost point of the Milky Way, near the North Pole (nāka), where—so says an Upaniṣad—the world of the Brahman lies, and from where one can see the turning of the two wheels, that of the day and that of the night.98

d) The sindhus of the RV

The idea of a celestial river, well known among many peoples, is very important for a correct interpretation of the RV. One recalls immediately the theory of Lüders, which posited that there are streams, lakes or oceans above the visible heavens.99 One can find several passages to uphold this theory, such as RV 3.22.3: ágne divó árṇam áchā jigāsy áchā devā́ ūciṣe dhíṣṇyā yé | yā́ rocané parástat sū́ryasya yā́ cāvástad upatíṣṭhanta ā́paḥ "O Agni, you go towards the flood of the heavens; you have spoken with the gods.../ (you go) towards the waters, the ones that are in the luminous space on the other side of the sun, and towards those that lie above the sun on this side here" (cf. also divó árṇa- in 8.26.17). Among other passages one will note the much discussed pāda from RV 2.28.4: váyo ná paptū raghuyā́ párijman "Like birds, they (the celestial rivers) fly rapidly on (their) course." As Bartholomae noticed, párijman is a compound of the words pári jmán "around (us) on the earth."100 That is a perfect description of the rivers, or the "branches"101 of the Milky Way, which turns around the celestial pole and occasionally forms a horizontal river near the horizon,102 or even two rivers interrupted by the earth at the horizon (seen from the northern part of India or from Iran): the eastern and western sindhu/həṇdu/samudra of the RV and the Avesta (see Figure 7).

e) The celestial mountain

The idea of the Milky Way also has consequences for the interpretation of the role of Varuṇa and of the "place of Ṛta." We know that Varuṇa goes in the evening into his watery dwelling (RV 2.38.8) in the Sindhu (7.87.16). Kuiper has demonstrated that this god, at the zenith of the nocturnal sky, holds the aśvattha tree by the roots, i.e., with the branches pointing downwards (see Figure 11).103 Still following Kuiper's analysis, the primordial mountain (giri-) should be similarly inverted during the night, and be situated in the nocturnal sky.104 But this remains more difficult for us to understand.

When the (nocturnal, "false" or "rock") sky105 ascends above the North Pole (nāka, the "stone"106), its base, the gigantic mountain,107 follows it, without our being able to verify it, since it disappears with the night in the Northwest. It is thus situated in winter in the eastern heavens, where we have already seen Plakṣa Prāsravaṇa situated; this is the source (or the "trunk") of the Sarasvatī and of the Yamunā which rise behind this cosmic mountain, and its "remainder," visible on the horizon at the moment of sunrise, is replaced by the giri of day: the Himavant, which is often called simply giri, uttara- giri.

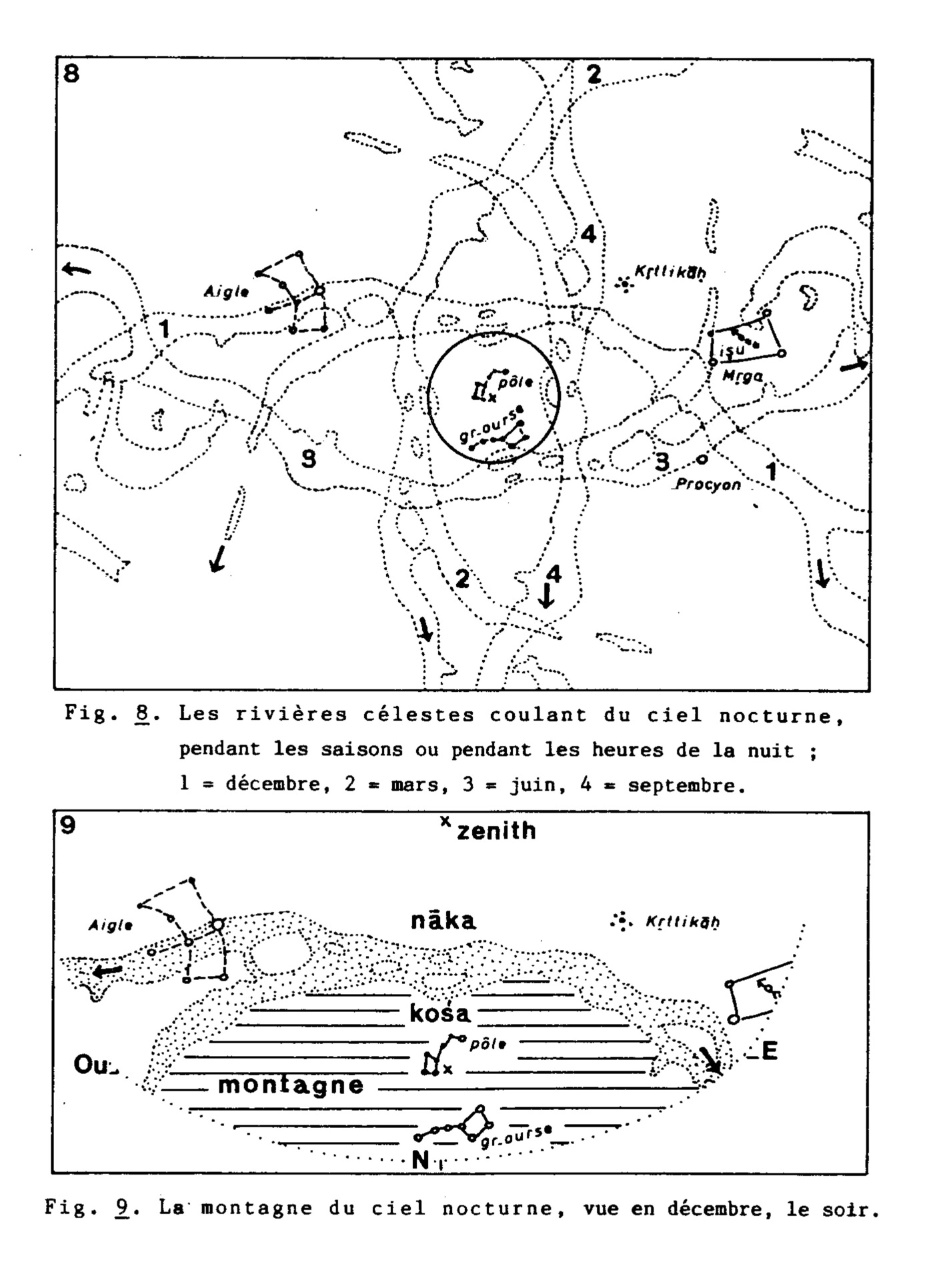

During the night, the Ṛta is situated, according to Kuiper, in the mountain, in the firmament (nāka) near the North Pole.108 Many other Vedic images and concepts are related to the notion of the Milky Way and its movement, as also to its diurnal counterpart, the sun and its daily movement. It is enough to recall here the devayāna and the pitṛyāna.

f) Other considerations

During the gavām ayana the sun makes its path each day returning a little bit more towards the north, or it moves on a plane more to the north than the ecliptic. At the winter solstice it is furthest south, at the summer solstice to the north. The Milky Way is oriented in the opposite direction.109 Each night, in winter, the Milky Way ascends to reach the North Pole, the residence of Varuṇa and the gods (in the sky). But, at the same moment, the sun moves (during the day and the half-invisible path during the night) from east to west, then returning from west to east (below the earth). At the winter solstice, the Milky Way, like the sun, starts to "go north."110

This means that at the moment of sunrise, the sun follows (in an approximately) opposite direction111 to that of the Milky Way.112 During the night, they pass on different sides. Hence, the opposition North/South is justified: the gods are in the north, Agni in the south113 (see Figures 8 and 9). The nocturnal sky has two "halves": a northern half, which is situated "up high" (where we find the two ocean "halves," or the eastern and western samudra, sindhu or həṇdu, § b., § d.), and a southern half, which is situated to the "low" (in the southwest, Agni and the pitṛ). Because dakṣiṇa- is always the opposite of uttara- and because the regions of the pitṛ and of Yama are not below but in the heights (in the sky), the expressions "north" mean "up above" cf. Skt. uttara- and av. Upara (apāxəδra-).114 With the descent of the Milky Way, the region of the pitṛs and of Yama will be the south even if it is "up above": Skr. dakṣiṇa-/ adhara- Av. aδara-. This development is very clear in Iranian: the north is the region of the *daēuua- (the ancient *daiua-: Ved. devá-), and the south is the residence of Yima, who widened the three worlds in a southern direction (stanza 2).115

VII

We return now to our point of departure: the pilgrimage along the terrestrial Sarasvatī. We shall read for this purpose another text, where we will find once again many of the elements already mentioned, namely PB 25.10.116 "They proceed to the consecration at the spot where the Sarasvatī disappears. (1) ...The adhvaryu throws the śamyā (yoke-pin). Where it falls, there is the gārhapatya (fire). (4) ...It is the "march of Mitra and Varuṇa."117 (9) ...With this (ritual) Mitra and Varuṇa conquered these worlds. Mitra and Varuṇa, they are the day and the night: Mitra is the day, Varuṇa the night. (10) ...With the Sarasvatī the gods propped up the sun. She could not support (the sun). She slipped. That is why she is slightly hunchbacked.118 They propped it up with the Bṛhatī (a metre). (11) ...They (the sacrificers) progress upstream (on the Sarasvatī). It is not possible to attain (the objective) when (one follows) the direction of the river.

(12) ...The objective is reached only when the progression along the Sarasvatī is accomplished. Where one can see the water springs forth, there is the Plakṣa Prāsravaṇa. After the sattra, one must perform the final bath in the Yamunā."119

The same text (PB 25.10) speaks in verse (15) of the "march" (yāna) and adds: "During forty-four mornings (beginning of the ritual at dawn), one progresses a horse ride forward, one thus goes (everywhere on horseback)."120 In comparison, the distance covered each day by throwing the śamyā and by walking, seems ridiculous (approximately 150 m.). Hence the question: why is such a distance too short to reach the source of the Sarasvatī, a distance of approximately 200 km? I think the ritual is a symbolic action, and the measurement of the distance by "horseback" can symbolize a celestial measurement: the Milky Way, which has a "horseback," the two samudra of Varuṇa, seen above ground. We find ourselves confronted by a problem that awaits clarification, as can be seen by the fact that, during the four months (beginning of the pilgrimage in December to March-April), in India at a latitude of 30 degrees, one cannot reach, on horseback, further than the Himālayas, and not even the slopes of the Himālayas, which are (as the crow flies) 200 km. from the "disappearing" of the Sarasvatī. The distance of forty-four days, or forty-four gallops of a horse,121 does not allow one to exceed 100 kilometers to the north. Such a measurement also makes no sense for a ritual action in which one makes progress by throwing a śamyā. That which is possible, on the other hand, is that one can say that the Sarasvatī goes beyond the Himālayas (or Mount Meru), up to the source which is at the North Pole.

We are no doubt in the presence of a measurement taken from the heavens: the daily course of the Milky Way ascends above the horizon each day in winter, by approximately 1-2 degrees, which amounts, in round numbers, to 40 days until the summer solstice, cf. JB 3.239.

According to JB 2.301, the sattra must be finished by the start of the hot season, which corresponds to March-April in the ancient calendar. Then, according to the same text, one advances towards the Yamunā. The distance by the route along the course of the Sarasvatī, beginning at its "disappearance" and then toward the northeast, does not take even forty-four days: one must calculate 600 km. from the point where the Sarasvatī disappears.122

The movement from the Sarasvatī to the Yamunā is given more clearly in another passage of the yātsattra, which describes the passage: "From the kārapacana onwards, they move from the southern to the northern shore of the Sarasvatī."123 (kārapacana signifies perhaps a locality. Bartholomae considered the pakva- of the yūpa or of the ājyasthālī, thus a mobile altar; Caland considered a locality named kāra-). After this passage to the northern shore, the pilgrimage goes from the southwest to the northeast and then to the north, towards the source of the Sarasvatī, and from there "passes" towards the Yamunā, thus in a southeastern direction, from where one takes the final bath, cf. infra.

The obscure name of a star, or more likely, the nocturnal residence of a god or an ṛṣi, is found in JB 2.299 (paragraph 156): at the source of the Sarasvatī lies the Plakṣa Prāsravaṇa, from where one can see the Trisaptanakṣatra "three times seven stars" (= the 7 stars of the Big Dipper + 2 groups of 7).124

The text specifies: "All those who start the sattra on the Sarasvatī (and who perform it well) will go up to the light (i.e. in paradise), unless those who during the sattra are (mistakenly) considered evil, who, themselves, become 'invisible' (adṛśya-) at the Prāsravaṇa. That is where he becomes invisible to men."125

This disappearance from the eyes of men could be accomplished through a ritual suicide in the Yamunā. The texts are silent on this subject, as always on the subject of violence and the fate of victims.126 But those who are killed during the sattra go automatically to the heavens. In consequence, the one who kills himself in the Yamunā (i.e. the Milky Way, the shining world) should himself also go to the heavens.127 This region exhibits other astounding properties: it is in the Śaiśava of the Sarasvatī (an arm of the river) that the one named Cyavana was rejuvenated.128 This word is derived from śiśu- "baby" and recalls the pond of the Apsaras in the Kurukṣetra, where the son of Purūravas and Urvaśī was born; it recalls also the role of the birds (identified with the Apsaras of Purūravas in ŚB 11.5.1.11) in the Indo-Iranian representation of the human cycle of rebirth.129 The Kurukṣetra region, i.e. "the island in the Rasā," "the doorway to the heavens" is therefore a land where it is equally possible to be rejuvenated and to be reborn.130

VIII

In conclusion, we can state:

- The sattras on the shores of the Sarasvatī are a reflection, a symbol of the path used by the gods, the ṛṣi and the souls in the heavens to travel to this "shining world" visible in the nocturnal sky.

- Up there (uttara-, upara-), in the firmament of the heavens, and above the Milky Way, lies the residence of the gods and also (later on) the world of the Brahman, from which one who has been delivered can see "the two wheels of the day and the night," i.e. the sun and the Milky Way.

- The doorway of this world is to the northeast, at the spot where the bifurcation of the Milky Way (in the Aquila constellation) becomes visible on winter mornings, around the time of the solstice.

- The ascension that proceeds slowly and by stages, symbolized by the pilgrimage along the shores of the Sarasvatī, corresponds to the upward movement of the "doorway" of the Milky Way, which is visible from winter into summertime. This movement in the direction opposite to that of the stars (and also of the particular stars visible in the Milky Way), this movement of the Milky Way—conceived of as a river—in its entirety, is advanced by the sacrifice of the gavām ayana, which culminates at the time of the two solstices, i.e. on the viṣūvat day in summer and the mahāvrata day in winter.

- In June and in July, at the summer solstice, when the sun reaches its highest point, the "doorway" of the Milky Way disappears to the west.

- This "doorway" must therefore be situated "up above" the earth, and must be moving towards the east, where it reappears in the winter during the morning hours. This movement corresponds to the path of the ancestors, the pitṛs.

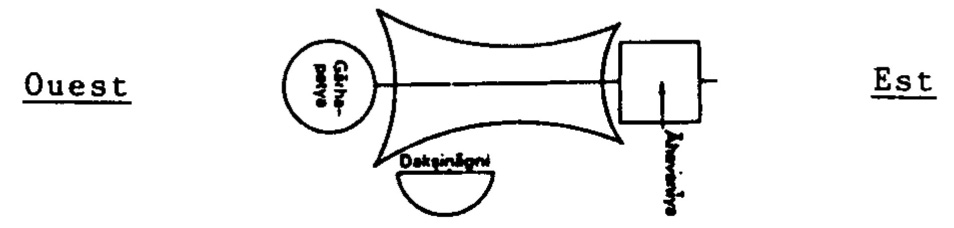

- This concept is the basis of a number of cosmological and religious notions in Iran and in India. The territory between the Sarasvatī and the Dṛṣadvatī becomes the vedi of the gods and of men, the place where the centre of the earth and of the heavens is situated, the axis mundi: at Plakṣa Prāsravaṇa at the foot of the Himalayas. This concept also lies behind the post-Vedic Meru (Sumeru), recognizable in the Harā (bərəzaitī) of the Avesta and the giri/aṣman of the RV. If one lets one's imagination roam,131 one can apply these ideas to the region of the Amu Darya (the Oxus), or even of the Volga (Gr. Rhā < *Rahā) and of the Dniepr, the Borysthénes of the Scythians (Herodotus 4.20, 26), see Figure 13.

- The movement of the nocturnal sky is fostered by rites like the Agnihotra, the Agniṣṭoma of springtime, the gavām ayana, or other sattras, including the yātsattra on the banks of the Sarasvatī, which have as their objective the achievement of immortality and attainment to the heavens.

IX

I hope that I have sufficiently demonstrated how important the observation of the night sky is to our comprehension of Vedic and Avestan texts. We should note that specialists in Vedic mythology and ritual have not been attentive to this phenomenon, perhaps because it is not as easily observed in the West as in the Near East or in India.

In the past few decades many explanations have been proposed for Vedic mythology. I think that it is necessary to ask whether the Vedic man did not think on the origin and end of his existence, on his life after death,132 and, as a result, on one of the paths of access to the heavens, to paradise, which I have attempted to describe.

This ritual activity,133 counterbalanced by faith in an automatic rebirth—in one's great-grandson—after an indeterminate period in Yama's paradise,134 is, in my opinion, a fundamental concern of the Vedic man.135

Key to Abbreviations

AB Aitareya Brāhmaṇa

ABORI Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute

Ai. Gr. Altindische Grammatik

AO Acta Orientalia

ĀpŚS Āpastamba Śrauta Sūtra

ĀŚS Āśvalāyana Śrauta Sūtra

AV Atharvaveda

BhP Bhāgavata Purāṇa

BŚS Baudhāyana Śrauta Sūtra

ChU Chāndogya Upaniṣad

DB The Behistun Inscription

IF Indogermanische Forschungen

IIJ Indo-Iranian Journal

JB Jaiminīya Brāhmaṇa

JBRAS Journal of the Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society

JUB Jaiminīya Upaniṣad Brāhmaṇa

KB Kauṣītaki Brāhmaṇa

KpS Kapiṣṭhala Saṃhitā

KS Kaṭha Saṃhitā or Kāṭhakam

KŚS Kātyāyana Śrauta Sūtra

KU Kauṣītaki Upaniṣad

KZ Kuhns Zeitschrift (Zeitschrift für vergleichende Sprachforschung)

LŚS Lāṭyāyana Śrauta Sūtra

Mbh Mahābhārata

MS Maitrāyaṇi Saṃhitā

MSS Münchener Studien zur Sprachwissenschaft

PB Pañcaviṃśa Brāhmaṇa

PS Paippalāda Saṃhitā

PS(K) Paippalāda Saṃhitā (Kashmirian version)

RV Ṛgveda

ŚB Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa

ŚŚS Śāṅkhāyana Śrauta Sūtra

TB Taittirīya Brāhmaṇa

TS Taittirīya Saṃhitā

VādhB Vādhūla Brāhmaṇa

VādhPiS Vādhūla Pitṛmedha Sūtra

VS Vājasaneyi Saṃhita

WZKM Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde des Morgenlandes

Y Yasna

Yt Yasht (Yašt)

YV Yajurveda

ZDMG Zeitschrift der Deutschen morgenländischen Gesellschaft

Figures

Figure 5. The rivers of the Kurukṣetra.

Figure 7. The two sindhu of the nocturnal sky, seen in December, in the morning.

Figure 9. The mountain of the nocturnal sky, seen in December, in the evening.

Figure 12. The wheels of day and night according to the Upaniṣad.

Figure 13. The Indo-Iranian rivers.

Notes

* Wales Research Professor of Sanskrit (Emeritus), Department of South Asian Studies, Harvard University, www.people.fas.harvard.edu/~witzel/mwpage.htm.

This article is the text of a lecture originally presented on December 16, 1983, organized with the help of l'ERA 94 of Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), Paris. It was subsequently published as "Sur le chemin du ciel," Bulletin d'Études indiennes (BEI) 2 (1984): 213-279, and is reprinted here in English translation by permission of the author. Michael Witzel translated the main text of this article from the original French, but the translation of the notes, along with the manual entry of the non-Unicode Sanskrit characters throughout the article, was provided by Gregory Haynes. Although many errors were subsequently corrected by Witzel (in June, 2024), any remaining inaccuracies are the responsibility of G. Haynes. The appended "Key to Abbreviations" was contributed by Nataliya Yanchevskaya of Princeton University. ↩

1 This essay, published in Breslau in 1894, was in fact directed against the "medieval" interpretation of the RV by Pischel and Geldner, in their Vedische Studien I-III (Stuttgart, 1889-1892). ↩

2 A point of view in favor in contemporary India, it seems. See the review of a work on this trend by W. Rau, IIJ 21, 1979, p. 281; and Proceedings of the 31st International Congress of Human Sciences in Asia and North Africa. Tokyo-Kyoto (ed. T. Yamamoto, Tokyo, 1984), p. 534. ↩

3 Roughly parallel to the theories of ethnologists, who sometimes followed the ideas of Indianists (in the 19th century) or linguists (in the 20th century). ↩

4 See Kuiper's books Varuna and Vidūṣaka (Amsterdam 1979); Ancient Indian Cosmogony (Delhi 1983), abbreviated here AIC; The Bliss of Aśa (IIJ, 1964), and also Schrapel, Der Avestische Kalender und sein Verhältnis zum vedischen Kalender (Bonn, 1961). We should note that specialists in Vedic mythology and ritual have not been attentive to this phenomenon, perhaps because it is not as easily observed in the West as in the Near East or in India. ↩

5 In the past few decades many explanations have been proposed for Vedic mythology. I think that it is necessary to ask whether the Vedic man did not think on the origin and end of his existence, on his life after death, and, as a result, on one of the paths of access to the heavens, to paradise, which I have attempted to describe. ↩

6 RV 9.113, 10.14-15, 10.154, AV 6.18, 18.2 ff. In certain cases it is said a "third of life;" cf. TS 2.6.13, KS 15.13, ChU (Chandogya Upaniṣad) 7.26.2. ↩

7 For details of these phenomena see H. Oldenberg, Die Religion des Veda, 4th ed., Stuttgart, 1923; A. B. Keith, The Religion and Philosophy of the Veda and Upanishads, Cambridge, Mass., 1925; L. Renou, Religions of Ancient India (Jordan Lectures 1951), London, 1953; Jaan Puhvel, Comparative Mythology, Baltimore, 1987; J. Gonda, Die Religionen Indiens I. Veda und alterer Hinduismus, Stuttgart, 1960; Jan C. Heesterman, The Broken World of Sacrifice, Chicago, 1993. ↩

8 In particular, Keith, RA VI; see also H. Wagenvoort, The journey of the souls of the dead to the Isles of the Blessed (Verh. Kon. Ned. Ak. v. Wet., Afd. Lett., N.R. vol. 67.2., Amsterdam, 1970). ↩

9 We should note the study of G. J. Held in ZDMG 104, 1954, pp. 77-96. I would also like to refer to a future article on the problem of rebirth in the Veda ("Rebirth"); cf. also TS 6.5.3.3, KS 28.2, KpS 44.2 (tasmād saṃvatsaraṃ jyotir upary-upari carati) and JB 2.25-26 (§ 117). ↩

10 In particular, the question of forty days (see below, n. 120), the period of the dyumna (see previously H.W. Bodewitz, Jaiminīya Brāhmaṇa 1, 1-65 (Translation and commentary), Leiden, 1973, p. 32 sq.), the intercalary "month" ("thirteenth month"), the names of certain constellations (with even a "dolphin," JB § 194), the problem of planets (graha?), shooting stars (MS 1.1.6: 124.2), Sirius and Orion (cf. B. Forssman, KZ 82, 1968, pp. 37-65). It is impossible to address all these problems here; I plan to discuss some of them in collaboration with M. P. Nieskens. ↩

11 This hymn offers some safe interpretations: it describes the rising of the moon (1), of the seven stars of the Big Dipper (9 amí yé saptá raśmáyaḥ), the setting of the five stars called ukṣan- (perhaps the nakatra hasta, cf. Kirfel, Kosmographie, p. 139; another interpretation in C. Kiehnle, Vedisch ukṣ und ukṣ /vakṣ, Wiesbaden, 1979, p. 82 ff.; cf. A. Scherer, Die Gestirnnamen bei den indogermanischen Völkern, Heidelberg, 1953, s.v. "Ochse"), which were in the middle of the high sky (10 amí yé páñcokṣáṇo mádhye tasthúr mahó diváḥ); and the position of the "well-winged" who are "sitting in the middle of the sky" on the (way) rising to the heaven, and who "keep out of the way of the wolf coming across the juvenile waters" (11 suparṇā́ etá āsate mádhya āródhane diváḥ / té sedhanti pathó vŕ̥kaṃ tárantam yahvátīr apáḥ): perhaps this "wolf" (near our Scorpio) is located in the branch of the Milky Way at the time of sunrise (12). In the Milky Way, we also find the Eagle (singular!), and very close to the "gate," cf. RV 3.7.7 and infra n. 69. See also "the walk of the high sky": divó bhṛató gātú (RV 1.71.2). ↩

12 On the Milky Way and the myths related to it in India, the Near East, Greece, etc., see M. Witzel, "Sur le chemin du ciel," Bulletin des Études Indiennes 2 (1984): 213-79. For other areas and for comparative evidence, see M. Witzel, The Origins of the World's Mythologies, New York, 2012. ↩

13 Macdonell, Vedic Mythology, Strassburg, 1897, p. 10 and Kuiper, AIC, p. 75. ↩

14 Cf. Atharvaveda Saṃhitā (AV) 18.2.31 and PS (Paippalāda Saṃhitā) 18.2.31; note the form árabdhā saptá raśmayaḥ ... svargáṃ ... ā́rohantī "the seven beams of light started towards the sky" (ārohantī is found in Paippalāda Saṃhitā, but the Śaunaka Saṃhitā has rodhantīm). Cf. the detailed interpretation of the starry heavens given in the Atharvaveda (by P. Thieme); cf. also the notes of the Atharvaveda edition of Whitney-Lanman. ↩

15 RV 10.136.1; KU 1.4; TS 7.5.7.4 = MS 4.7.5:99.1. ↩

16 AV 6.89.3, 13.2.30; JB 1.85, 2.298 = PB 6.7.10, 6.7.11; ŚB 6.6.2.4. ↩

17 Therefore saṃvatsaró vái svargó lokáḥ MS 4.67: 90.1. ↩

18 Due to precession, the celestial North Pole is today in the Little Dipper, but between 2000 and 1000 BCE, it was between it and the Dragon. In about 1800 BCE, the position of the pole was defined by three remarkable stars of the Little Dipper and the Dragon, which formed a triangle (cf. R. Muller, Der Himmel uber den Menschen der Steinzeit, Berlin-New York, 1970, p. 137). On these phenomena, as on other facts of astronomy, we can read "Astronomy with the Naked Eye," by A.F. Aveni, in his work Sky watchers of Ancient Mexico, Austin (Texas), 1980, pp. 48-132. Most of the data in this article is calculated for 20 degrees of northern latitude (location of Yucatan, the Mayan territory), but they are better suited to the confrontation of Vedic facts (Delhi and Kurukṣetra are located at approximately 30 degrees North latitude) than our maps, which are calculated for approximately 50 degrees north latitude. This study is of extreme value for the assessment of Vedic (and Iranian) phenomena. ↩

19 The maps are drawn for 30 degrees north latitude (Delhi, the Southern Panjab, Sīstan, and also Basra, Cairo). Under our latitudes (about 50 degrees North), we can see a portion of the night sky above the North Pole greater than at 30 degrees North. The Big Dipper is visible in our regions all year round, but not in India. Nowadays it is visible roughly from January to April and from July to October (cf. ŚB 13.8.1.9, Mbh III 11855). The date of heliacal rising of a star depends on the elevation from the equator; it varies about one to two days for one degree. Finally, today, because of the precession, the constellations have a position more Western by 42 degrees compared to that of Vedic times. Concretely, the Pleiades rise earlier today than at the time Vedic (ca. 1000 BCE). ↩

20 pratīpam iva vai svargo lokaḥ "partially against the flow, the luminous world (moves)" JB 2.298: 288.8; pratikūlám iva hītás svargó lokáḥ "in fact, from this point, the luminous world (becomes moves) partially against the flow" (i.e. from the initial moment of gavām ayana, of the winter solstice) TS 7.5.7.4, JB 1.85, PB 6.7.10, KS 33.7. The counter-current movement is opposite to that of the sun. Similarly, a given star "sinks" below the pole, and then goes up, against the flow, towards the pole, cf. TS 5.4.1.4 tásmad prācī́nāni ca pratīcī́nāni ca nákṣatrāny a vartante. ↩

21 Cf. JB 2.298 et KS 33.7 cited above. ↩

22 It is impossible to discuss this ritual here. I am happy to indicate the treatment given by TS 7.5, KS 33-34.5, PB 4-5.10 (cf. KB 19.3). We will also notice that the hotar, seated on a swing, is balanced from east to west: an image of the movement of the Milky Way (ĀpŚS 21.17.13, AĀ 1.2.4, ŚŚS 17.18). This movement differs from the annual movement of the sun: northeast to southeast to north. But the two "tails" of the Milky Way, including in particular the "gate" (cf. n. 69), is not found in the east (or west) only at the solstices, in the morning (or evening, respectively). They contribute to the movement of the sun during the night (cf. n. 118), and on its return to the east, between the waters of the Milky Way. ↩

23 The idea of the cord is very important to Vedic ritual and mythology; see "Rebirth." The Milky Way was considered by the Mayans like an umbilical cord, cf. Aveni, op.cit., p. 97; for a ritual reflection of this conception, see below n. 25. The Vedic Indians also describe an umbilical cord between the earth and the sky (the sun), and compare it with that which connects man to his ancestors, up there, in the paradise of the gods or Yama; cf. note 60. ↩

24 The identity of the stars of the Eagle is doubtful, but cf. note 69, on the Milky Way gate, below. According to ŚB 12.2.3.7, the year of sattra is the Eagle; AV 10.8.13 describes the wings of the celestial haṃsa (sahasrāhnyá-); we read devayāna- in the PS(K) version. Cf. note 70. ↩

25 The vedi extends between the fires gārhapatya (the earth) and āhavanīya (the sun, the sky), has the shape of an elongated trapezoid, whose sides are concave: [diagram placeholder]. This position between "earth" and "sky" is symbolic of the Milky Way. According to the same schema, the Kurukṣetra is the devayajana (n. 50), and the doāb of Gaṅgā and Yamunā is called antarvedi—cf. ĀpŚS 4.5.1. ↩

26 RV 1.154.5-6 is also very interesting: padé paramé refers to the Milky Way, and gā́vo bhū́riśṛṅgāḥ at dawn, or at the extremities of the Milky Way? ↩

27 The Milky Way is only rarely mentioned in works that deal with Vedic mythology; and when it is mentioned, it is only very incidentally: cf. Weber, Abh. der Preuss. Academy Wissenschaften, Berlin, 1893, p. 84 (Aryaman's Way) and Festgruss an R.v. Roth, Stuttgart, 1893, p.138 (see Whitney's remark on AV 18.2.31); Hillebrandt, Vedische Mythologie. Breslau, 1927-1929, I, p. 383 and II, p. 359; on the Rasā, Whitney - AV 4.2.5; Griswold, The Religion of the Rigveda, London, 1923, p. 284; Aufrecht, ZDMG 13, 1859, p. 498; Hertel, Die awest. Herrschafts- u. Siegesfeuer, Leipzig, 1931, p. 15, 51, 119.— Lüders (Varuṇa, Gottingen, 1951-1959) has observed the "river of milk" (and other pleasant drinks), but has not come to the conclusion that svarga- loka- = Sarasvatī = Milky Way, cf. Varuṇa II, p. 351 ff. We find absolutely nothing on the Milky Way in the aforementioned book (n. 11) by Scherer: Die Gestirnnamen bei den indogerm. Völkern. None of these philologists observed the importance of the movement of the Milky Way (during each night and during the year), with the exception of Schrapel, loc. laud., n. 14. ↩

28 The original dimension of this hymn, which has eighteen stanzas in the RV, is uncertain. According to ŚB 11.5.1.10, it is "the hymn with fifteen stanzas." ↩

29 With a few exceptions: Hertel, Hillebrandt, etc. (see above n. 27). ↩

30 Cf. P. Thieme, Der Fremdling im Ṛgveda, Leipzig, 1938, pp. 110-116; Kuiper, AIC, p. 155; at AV 18.4.8 is found sárasvatī sū́ryā "Sun-Sarasvatī." ↩

31 Cf. Macdonell, Vedic Mythology, p. 83; the Vedic term is particularly sindhu (cf. the name Indus: Sindhu, cf. Thieme, in ZDMG 110, 1960, p. 301 sqq. = "sindhu of the gods"; nadī is rare in this sense. ↩

32 RV 7.36.6, 7.95 (27 stanzas); AV 6.89, 18.3, etc.; cf. Kuiper, AIC, p. 145 sqq. ↩

33 RV 2.41.17, 10.184.2, etc. For Av. Arəduuī Sūra Anāhitā, see below note 89. ↩

34 AIC, pp. 35 sq., 78, 80, etc. (cf. n. 73). On the course of the sun, we will read JUB 4.5.1: after lying down, he is aśmasu "in the stones." This passage offers a good description of divine activities in relation with the sun during the twenty-four hours of the day. MS (3.11.3: 144.5) says: patáṃ no aśvina diva, pāhi náktaṃ sarasvati (cf. also VS, KS, TB); how can we explain the link between Sarasvatī and the night? ↩

35 See the description in Kirfel, Kosmographie, p. 43; and Kuiper, AIC, pp. 68 and 82 ("The bliss of Aša"). ↩

36 Cf. the edition and commentary by Caland, AO 4, 1926, p. 198 (§ 91). ↩

37 This is indeed the post Ṛgvedic idea. In the RV, we talk about the third sky, but we do not make a distinction between the three levels, cf. Kuiper, AIC, p. 44 and VaV, p. 38. We find the pradyāuḥ (AV 18.2.48), various loka (JB § 143), the varṣman (KS 36.6), supreme sky. In the Avesta, the supreme paradise (i.e. light) is superimposed on the three others (Vīštasp Yt., 63). ↩

38 But it corresponds to the heaven of Varuṇa (Kuiper, AIC, pp. 82-3. The kingdom of Yama is often placed in the southern region, in hells; it is a relatively recent idea, which developed from of the opposition North = uttara- "above": South = X, etc. ↩

39 RV 10.63.10 devā́nām yáthā yugé prathamé ... ékam agním ... yajñáir divám āruruhúḥ "As in the first age... the gods, alone Agni, they mounted to the heavens by means of sacrifices;" see also ŚB 1.7.1.5, TB 1.7.4, KS 9.6, etc. On the idea that all of the gods are not in the sky, cf. AB 3.21, PB 5.4, 8.2, ĀŚS 5.6, etc. ↩

40 Cf. Kuiper, VaV, p. 242 sqq.; and TS 7.2.1. ↩

41 TS 7.1.4, 7.2.5, 7.4.6. ↩

42 Cf. JB 2.302: lokānāṃ puṇyatamo yam ... saptarṣaya ārdhnuvan. In the Avesta, the hapta srauuō (plur. acc.) are another constellation, probably the Pleiades (the Kṛttikāḥ in India). At 30 degrees of northern latitude, the Big Dipper is visible throughout the year; in the South, only for part of the year, see n. 19. ↩

43 On the path that leads to the gods, cf. RV 10.2.7, 10.14.2, 10.15.14. 10.30.1, 10.51.2; this path is not safe (RV 3.54.5); the gods have closed the sky: ŚB 1.6.2.1, TS 6.5.3.1. AB 3.42. ↩

44 Symbol of the movement of the sun (cf. RV 1.164.2 and 12), which we encountered among many peoples: for example, among the Mexicans, four men, their legs tied with ropes to a pole, stood drop and go down, turning around this pole (see the month of September in the UNESCO calendar for 1984). About a path to the ends of the earth, to the paradise of Yama, cf. RV 10.114.10. ↩

45 See Hillebrandt, Ritualliteratur. Strassburg, 1897, p. 154 ff. (on the yātsattra, p. 158 ff.) and Heesterman, "Vratya and Sacrifice," IIJ 6, 1962, p. 1-37. ↩

46 AB 2.17: sahasrāśvine vā itaḥ svargo lokaḥ; KB 8.9 speaks of twelve days. ↩

47 Cf. AB 4.21.4 and Schrapel, op.cit., p. 33. See also TS 7.3.4, 7.4.4.3, 7.5.4.1, 7.5.8.4, PB 4.6.17 and ŚB 4.5.8.11, TS 7.1.7.4, JB 1.87 (§ 11). I can only mention in passing the relationship between the Milky Way, the tantu of man (cf. n. 23 and 60), and procreation, relationship evident for Sarasvatī and Av. Arəduuī Sūrā Anāhitā (see.Yt. 5, and also Yt. 4.65). Note that in the Avesta the Frauuaši carry the embryo (or possibly the soul?) of men living and unborn paitii.āpəm: against the flow. ↩

48 JB 2.297 sqq., PB 25.10-13, TS 7.2.1.3-4; cf. KS 33-34, AB 2.19, BŚS 16, 29-30, ĀpŚS 23.11.4-13.15, ŚŚS 13.29, ĀŚS 12.6, KŚS 24.5.25-41, LŚS 10.15-19.4; et JB 2.339. ↩

49 See Ecology and archeology of W. India (ed. D.P. Agrawal and M.B. Pande), Delhi, 1977. The problem of locating the Vedic Sarasvatī is famous. In the period of Middle Vedic texts (the Brahmaṇas), it is no longer, as in the RV, a majestic river, but it is lost in the sands of the desert (vinaśana and upamajjana: see below). The two branches of the celestial Sarasvatī, the Milky Way, represent this vinaśana well, as we can see on a star map. M. I. Khan's book, Sarasvatī in Sanskrit Literature (Ghaziabad, 1978), gives many facts (Veda, Puraṇas, and some passages from classical literature), but not of adequate interpretation. The author conceives Sarasvatī as a goddess and an earthly river. Its interpretation is very dependent on that of exegetes like Sayāṇa, Mahīdhara, and the Indianists of the 19th century; he offers a fanciful discussion (p. 12 ff.) on the Sarasvatī in a geological period where there was a sea in place of the Rajasthan, etc. ↩

50 It is notable that the natural appearance of Kurukṣetra does not meet the requirements of the Vedic sacrificial ground. It presents a slope from the northeast towards southwest (gradual, between approximately 200 m at its exit of Siwalik, and 85 m., near Thanesar), while the texts prescribe a slope from the west to the east or the northeast: VadhB (cf. Caland, AO 4, p. 198): sarve lokeṣūdak prāg eva parāṅ priyā "All the worlds, to the north, to the east (and) even to the west, are pleasing." The north is doubtless superior—cf. TS 2.4.6-7.1, ŚB 2.2.3.2, 3.1.2.10. See also the ritual position which is given to the northeast in the yātsattra that we already mentioned. For this passage of the Vādhūla Brāhmaṇa, one can also think of the "worlds" that have a connection to orientation, that is north = gods, south = pitṛ, west = men (or the world of the Brahman, ChU 3.11.6), east = animals (or Indra, see ŚB 6.5.1.5 etc.) —cf. ŚB 2.2.3.2. For the role of devayajana, cf. TS 2.1.3.1; ŚB 1.4.1.10. See also AB 3.42 (the gods are to the north). ↩

51 The passages cited are at JB 2.297-299, 2.301-302 (§§ 156-158). Note also parallel texts, all in PB 25.10-13, for this important passage. ↩

52 This literal interpretation goes back to the AB. The śamyā here is still the simple peg with which one ties the oxen to the yoke, and not the yoke. I thank J. C. Heesterman for this information. ↩

53 Cf. n. 46. ↩

54 yāvat samdravā saṃyajīta vārttāpa evātaḥ kurvīta "Whatever you spend on the river (the earthly Sarasvatī), do it for the [objective] which concerns the water," in other words, says the commentator: "the river (having been crossed)," thus for the rain, fertility, health, or (cf. comm.) "for the water which flows (always)," thus paradise. JB 2.298 paragraph 156: 248.16-17. ↩

55 Cf. also ŚB 11.8.4.6 (táto haivá sá utsasáda: the sattra of Keśin), with Eggeling's comment. ↩

56 ŚB 3.1.2.10 et 14.1.2.11 states it very clearly: one (says) that Kurukṣetra is free from animals (vaiyaghrapada). Sacrifice must be performed there. He who lives there where the divine Sarasvatī (flows) towards the east (cf. n. 66): certainly this is the best of sacrificial grounds (devaśraiṣṭhíya). The order is the following: (1) Sarasvatī, (2) Dṛṣadvatī, (3) at the confluence of the two, (4) Sindhu/Indus, (5) Gaṅgā, and finally at the Yamunā. ↩

57 For the water of the Sarasvatī (on which one must carry out avabhṛtha, see ŚŚS 13.29.8-9): Gaṅgā or Yamunā, flowing from the Plakṣa Prāsravaṇa, could well be a substitute; and note that the texts in question state one must "touch the Ganges" (gaṅgām ápy abhyupeyāt; cf. PB 12.9.7, 25.11.1; JB 2.298 paragraph 156). ↩

58 The AV describes the first bath since "birth" (i.e. after a birth on this earth) and expresses the wish that this bath be the vehicle to the future divine world, as, after the yātsattra, by the avabhṛtha; this final bath transforms the yajamāna, from a semi-divine person into a normal man (cf. Heesterman, IIJ 6, 1962, p. 19), who wishes to live his "hundred years," cf. PB 4.6.19 and n. 47. ↩

59 Cf. A. Erman, Die Religion der Aegypter, Leipzig, 1934, p. 122. ↩

60 Cf. also ŚB 6.7.2.11; KB 10.5; AB 3.31, 5.7 (Kāṭhakala at the place of the sacrifice: vyū́ha-). At the center of the sacrificial ground is the āhavanīya fire; that represents Yama (ŚB 9.5.2.15). We shall note that the tantu rope (cf. n. 23) is very important in the ritual and its mythology. For the double significance of a terrestrial and mythical object, cf. Bodewitz (note 10 above, p. 29). ↩

61 And of all the ritual, obviously, cf. AB 4.6, JB 2.297. ↩

62 See, in particular, Oldenberg, Vorwissenschaftliche Wissenschaft, Göttingen, 1919; Schayer, "Die Weltanschauung der Brahmaṇa-Texte," Rocznik Orientalistyczny II, 1924, p. 57 ff.; Witzel, On Magical Thought, Leiden, 1979. ↩

63 And the cosmic center of the earth, cf. note 80. ↩

64 See also the interpretation of ŚB 12.2.1, where the sattra is equivalent to a crossing of the ocean; the first and last days are tīrtha "fords;" the middle day (viśūvat "summer solstice") is an island, which is visible in the Milky Way, on the eastern horizon, in the constellation Gemini. ↩

65 It is difficult to imagine this practice. The Sarasvatī is 180 km long. at least (Imperial Gazetteer of India 22, p. 97), or 600 km (from the Himalayas to the confluence of the Naiwal). ↩

66 At this junction flows the "divine" Sarasvatī to the northeast (cf. ŚB 3.1.2.11, in n. 56 and PB 25.10.16; devī́ yā́ prācī́ pravṛttā); cf. JB 2.297 paragraph 156. 248.18. See below, section VII on the significance of the movement towards north and east; see also note 114. ↩

67 On the winter and summer solstices, cf. ŚB 1.6.1.19 (the two gateways, dvāra, § IV) of the year, went to the bright sky." ŚB 1.6.1.19 says that these two gates are spring (vasanta) and winter (hemanta). ↩

68 The Aquila constellation, from November to April (before sunrise in the morning). ↩

69 ŚB 6.6.2.4 tasyá sá dvā́r bhávati "this (direction) becomes its doorway." Which is called devadvāra-, cf. ChU 8.6.5; JUB 1.5.1, 4.26.1; or the doorway to the luminous world (svarga). At ŚB 6.6.3.1-7, which corresponds to TS 6.3.3.5-10, one can read that the adhvaryu brings (all the priests) from the south to the north and from the west to the east (yád vái dakṣiṇataḥ pūrvā́bhyāṃ digbhyām uttarāṃ prācīm ca digám abhivartáyati, 6.6.3.1; see in particular TS 6.3.4.4 and 6.3.5.2), so that he can achieve the heavens (etā́d ásmād uttarátaḥ svargá u lokó, sá vāí táṃ lokáṃ ... nákṣatra "from here, the shining world is situated in this direction [towards the north]; certainly it means (idam eva vai tan nakṣatram) a group of fixed stars." ↩

70 At about 42-47° NL, we can observe the "gate" (bifurcation) of the Milky Way in the east, during several weeks before the winter solstice. At 30° NL, the observations are less clear; the bifurcation is beyond the horizon. The AB 3.42 passage (yó 'dhyuttarato 'vagād uddiśam etám ténopa yāma devā́ñ chandasā́dhigaccha asúrebhyo vai devā́ udag udagañ chandasāpāyan "He who arrived at this northern direction, by this one, go to the gods; or: obtain the gods by means of the metres! In truth, the gods fled to the north from the Asuras thanks to the metres") describes it approximately: near the end of the year, before sunrise, the bifurcation of the Milky Way is visible at a northern position. The gods have abandoned the southwestern part (where Agni lives, cf. infra n. 112; the region of the pitṛ, as well as that of Rudra and of Nirṛti, cf. ŚB 1.2.1.5 and 6.6.3.6-7), and took refuge at the Milky Way, i.e. to the north, or rather to the northeast of the visible hemisphere (see Figures 3, 4 and 6). ↩

71 This interpretation corresponds to Ṛgvedic facts, cf. RV 10.88.15 and 10.17.8 (Sarasvatī with the pitṛ- in the same chariot). Ashkun, a Kafir (Nuristani) language, retained dea wirecu "the way of the gods, the Milky Way" (Turner, A Comparative Dictionary of the Indo-Aryan Languages, London, 1966, 6523).—Manichaeism knows the "column of Glory," "of light:" Parthian bāmistūn. Opinions of late Vedic texts and different Upaniṣads present a new solution: the devayāna ends in the sun, the pitṛyāna in the moon, from where the souls must return to earth; for another devayāna, cf. Thieme, Kleine Schriften, Wiesbaden, 1971, p. 95. Sarasvatī also plays a role in the anvārambhanīyaiṣṭi, cf. Krick, Das Ritual der Feuergründung, Wien, 1982, p. 496 sq.; see above n. 47. ↩

72 The gavām ayana "the walking of the cows" is one of the important rites (cf. already n. 22), which are linked to the course of the year, and especially to its "critical moments," such as the agnihotra (daily), the dārśa/paurṇamāsa- (semi-monthly), cāturmāsya (three times a year), soma (once a year). The gavām ayana lasts for a whole year. This name was not explained by Caland (PB 4.1.1). There is a necessary correlation with the movement of the sun, which rises every day at a different place. Uṣas, the Aurora (identified with a cow, gau) must appear 360 (or 365) times in a different place: these are the 365 gāvaḥ, whose annual walk constitutes the gavām ayana. We will note that this rite is a "swim on the ocean of the year," cf. KS 33.5, TS 7.5.3, etc.. The ascension to heaven is done "with the luminous shine (of the stars)": jyotiṣmatā bhasā (KS 34.8). ↩

73 Kurukṣetra is therefore the center, the madhyadeśa, cf. AB 38.3: asyām ...madhyamāyām...diśi ye...Kurupañcālānām rājānaḥ. See Bosch, The Golden Germ, The Hague, 1960 and Kuiper, AIC, p. 32. ↩

74 Madras manuscript, No. R 4375 (StII 1, 1975, p. 89). See also VS 16.51: Rudra's weapon on the highest tree. On the plakṣa, the tree as the axis of the world, cf. Kuiper, AIC, p. 143 and Thieme, Kl. Schr. p. 84 sqq. On the function of the yūpa, and in particular its upper part, cf. TS 6.3.4.8. Nothing new at Bharadwaj, "Plakṣa Prāsravaṇa," ABORI 58-59 (Diamond Jubilee Volume), 1978, pp. 479-87. By establishing a sacrificial ground, the yajamāna and the priest create for themselves a center of the universe (cf. n. 25). There exists a monastery located "in the middle of the world," at vhumi-age-majhi (cf. Schlingloff, IF 72, 1967, p. 320—taken up by Eggermont, IIJ 14, 1972, p. 82). ↩

75 The celestial river is also called Sindhu (cf. Lüders, Varuṇa I, p. 153); the celestial Sindhu is the mother of the earthly Sarasvatī (RV 7.36.6). ↩

76 We can speculate on the name of this river: an etymology from yam-, of the yamá : yami couple, is attractive. The suffix -una- also appears in Varuṇa (cf. Hamp, IIJ 4, 1960, p. 64); the Yamunā would therefore be the "twin" of Sarasvatī. ↩

77 In fact, one becomes mad if one does not step down from heaven, as has been mentioned earlier (n. 47). This explanation also means that the heavenly river flows around the pole in two directions: towards the west (by the force accumulated up to the autumn solstice due to the gavām ayana) and towards the east – because this force, from this moment on, has ceased to work, and because the waters of the Milky Way reflow automatically. Therefore, JB 3.150 perhaps presents an exception: Ukṣṇa Randhra Kāvya (like Uśānas Kāvya) has gained heaven (svarga-loka-) by climbing (ārohaya-) against the flow (pratīpam) of the Yamunā, by discovering in the waters a route for himself (me vartmāni, svavartmāni) that he has used as a path (niyānam); cf. the commentary of Caland. The parallel text, PB 13.9.19, does not offer this particular information. ↩

78 Cf. also ŚB 13.8.1.13: waters to the north or west of a tomb. Such pilgrimages are comparable to Bhujyu's "journeys" of ecstasy (RV 1.116.3-5) and, in the Avesta, of Pāuruua (Yt. 5.61 sqq.): both rise above a vast expanse of water in the sky. ↩

79 See, among others, E.W. Hopkins, "Sacred Rivers of India," in Studies in the History of Religions offered to C.H. Toy, New York, 1912, p. 213 ff.; Epic Mythology, Strasbourg, 1915, p. 5 sqq. ↩

80 Cf. the Purāṇas, and also Mbh., in particular III 10720 sqq. (the Ganges becomes four rivers to fall to earth, according to the four cardinal directions), also III 10776 (Śiva), 10782; cf. Hopkins, Epic Mythology, p. 100. ↩

81 Hopkins, Epic Mythology, p. 6 ff.; M. Eliade, Le Yoga, immortalité et liberté, Paris, 1954, p. 328 ff. ↩

82 PB 12.9.4. JB 2.298-299: Keśin's example illustrates the fate of a virtuous person who reaches the highest goal through pilgrimage. ↩

83 Cf. infra, on the Avestan doctrine, paragraph VI, b. ↩

84 Cf. vār ā vayanti etc. in RV 9.91.1 (= pári + i- Grassmann, Wb.); the etymology of Geldner (heavenly) pari.jman (the land around the earth) is more convincing (for Ved. porijman-) than the one recently proposed by Kuiper (AIC, p. 80: Ved. parivrajman without a hitch, the object, through the intermediation of a jman = the Sindhu). ↩

85 For the Iranian evidence, cf. H. Lommel, Die Yašt's des Awesta, Göttingen, 1927, in particular pp. 71-84; see the detailed summary in F.B.J. Kuiper, AIC, pp. 134-56. ↩

86 It must be said that, in the Avesta, one begins to describe the Milky Way: Yt. 8.12; for the Veda, cf. Yt. 5.95-96 and JB 3.271. Cf. for Av. vourukašam zraiiaŋhəm and Yt. 5.4. ↩

87 saēna (Yt.12.17) = Ved. śyená. Yt 12. 16-25 offers a perfect description of the movement of the Milky Way (Vouru.kaša, Ranhā) around the cosmic tree, and the primordial central mountain (Harā, Haraitī), from where the Arəduui emerges, and where there are no night and darknesses (cf. Ved. svar aśman); the stars, the moon, and the sun turn around that celestial mountain. With xara (= Ved. khara) which is found there (Y. 42.4) one can connect the donkey of Yama at RV 1.116.2 (and 1.162.21, 5.53.5); cf. gardabha and rāsabha in RV. Is the course (ājí) of Yama his movement with the night sky? ↩

88 JB 3.66 upari(-) śyena- svarga- loka- (cf. ASv. upairi.saēna for the Hindukush); at JB 3.270, the expression designates the heaven of the Atharvans. ↩

89 On the Yt. 5, which is dedicated to him, see the thesis of N. Oettinger (München, 1984). I refer to Lommel's theory (op.cit. n. 32). There river/goddess Arəduuī Sūra Anāhitā is above the sun (Yt. 5.90) and in the middle of the stars (Yt. 5.132). Also note that its waters flow in winter as in autumn—which never happens in Iran and Turkestan. The quantity of water is maximum in autumn, following the thaw and spring rains. ↩

90 Chariot racing term, used for points in the "race" of the sun (solstices). In the Avesta, dūraẽ.uruuaẽsa- (Yt. 13.58) it is a point of the "course" of the stars. On Saramā and the Paṇis, cf. H.P. Schmidt, Bṛhaspati und Indra, pp. 241 and 189 sqq.; see also RV 10.114.10. ↩

91 An old conjecture by K. Hoffmann (in his lectures). ↩

92 The movement of the Milky Way also explains that the female dog Saramā does not know where the Paṇis hiding place is (on the "island of Rasā"); cf. H.P. Schmidt, op. cit., p. 189. Often the Rasā appears like a mythical distant river, cf. RV 10.75.6: a small (?) river which flows into the Indus (up there, in the Himalayas); it is also the sixth country, in V. 1.19: upa aoδaẽšu raŋhaiiā-, cf. Figure 13. ↩

93 Sindhu and Rasā are found together at RV 4.43.6. ↩

94 Often misinterpreted: "im westlichen und östlichen Indien" (!) according to Bartholomae-Wolff. Thieme includes: "frontier (of the inhabited world)," therefore "sea, ocean" and "border river" (i.e. the Indus). cf. "Sanskrit sindhu-/Sindhu- and Old Iranian hindu-/Hindu-" in W.B. Henning Memorial Volume, London, 1970, p. 447 ff. ↩

95 Cf. RV 10.136.5 (eastern and western ocean) and 10.30.10; only one stanza (ĀpŚS 5.11.6) speaks of the two sources of the Sarasvatī "which must kindle themselves." ↩

96 Varuṇa II. pp. 396-401. ↩

97 AIC, p. 138 ff. ("The Heavenly Bucket"). This kośa is symbolized in the mahāvrata ritual by a kumbha worn by young girls on their heads (JB 2.404: § 165). The head is the symbol of heaven (divo rūpam yan mūrdhā). See also AV 10.8.9: a pitcher (camasa) with two holes, overturned near the Seven Ṛṣi. ↩

98 KU 1.4; cf. Sur le chemin, note 111. ↩

99 Varuṇa I, pp. 111-21, 138-166, 239 ff., 271-5; II, pp. 351-9, 375-89, 588 sq. See, however, the criticisms of K. Hoffmann, in Aufsatze zur Indoiranistik (Wiesbaden, 1975-1976), p. 47 sq.; and Kuiper, AIC, p. 79. ↩

100 Geldner, Vedische Studien II, p. 225 (at RV 9.91.1), cf. TS 7.1.20d; see Bartholomae, BB 15, 1889, p.25; Wackernagel, Altindische Grammatik III, p. 243. K. Hoffmann, Aufsätze p. 48) refutes the theory of heavenly rivers and translates pòrijman by "ringsherum, allenthalben (on the earth)," cf. Sur le chemin, note number 102. ↩

101 Hence the idea of the four rivers of the epic and the Purāṇas, which circulate and flow from Mount Meru/Sumeru towards the four cardinal points (cf. Lüders, Varuṇa I, p. 284 ff.). See the bibliography given by Kuiper, AIC, p. 142 n. 1), and Kirfel, who compares RV 1.62.6 (Kosmography, p. 40). Hertel did not observe this fact: he thinks of two or three "branches" visible in Central Europe, which "flow" from the North Pole. For the three rivers of the Veda, cf. Lüders, Varuṇa II, pp. 692-3). On the four rivers of heaven, see Lüders, Varuṇa I, p. 276 ff. We note that the Lüders map (with the Buddhist idea of the four rivers) corresponds more or less to the geographical reality, and also to the astronomy, cf. Figure 1. ↩

102 At approximately 50 degrees north latitude, we see the sindhu and samudrá at the end of the world, and below the ground; about hŕ̟dya-samudra, cf. Kuiper, AIC p. 148: "The term samudra was used in Vedic times both for the oceans that surrounded the earth in the mythical cosmology and for the cosmic waters under the earth;" see AB 8.15 (antād ā parādhāt pṛthivyai samudraparyantasyai), AV 4.16.3, 13.2.30, and RV 10.136.5 (PS 5.38), cf. infra, n. 113. JUB 1.25 describes the ocean (samudra) as a border between mortal and immortal, between earth and heaven. The sun rises at the shore of the ocean (thus across a visible "ocean"?): that is why it has a stable position in the immortal world (the "heaven" and the subterranean mountain at the other side of the ocean?); cf. JUB 4.5.1: supra, n. 34. ↩

103 Kuiper, AIC, pp. 49, 99, etc. With the ascension of Varuṇa to the zenith of the nocturnal heaven, Yama and his paradise also move. I think the movement of the Milky Way from the left (against the flow: prasalavi, and not pradakṣiṇa) plays an important role in the sinistroverse tendency in funeral rites and in the rites intended for the pitṛ; cf. Lommel, Kl. Schr. p. 101 and Caland, "Een Indogermaansch Lustratie- Gebruik," Mededeelingen der K. Akademie ..., Amsterdam, Reeks IV. Deel II, 1898, pp. 275-325. ↩

104 AIC, p. 35 sqq.; cf. also Hertel, Die Sonne und Mithra im Avesta, Leipzig, 1927, p. 112; and Reichelt, "Der steinerne Himmel," IF 32, 1913, pp. 23-57. A similar idea can be found in JUB 1.25, 4.5.1 (cf. n. 34 and 102): the stars are lights shining through the holes of the stone sky; likewise the sun, according to JUB 1.3.1. ↩