Old Norse Yggdrasill

An Etymological Re-evaluation

Dedicated to Michael Witzel on his 80th birthday (July 18, 2023)

Abstract

The etymology of Old Norse Yggdrasill is disputed. While sometimes taken to mean "Odin's Horse," this interpretation involves a number of difficult assumptions and furthermore cannot be resolved into known Proto-Indo-European roots. This paper discusses earlier etymological attempts and then presents an alternative etymology that reflects both the mythical axis-mundi function of Yggdrasill as well as the Indo-European origins of its name. The appropriateness of invoking nature symbolism in mythical interpretation is addressed through an analysis of the Greek myth of Leda and the Swan.

Key words: Yggdrasill, Etymology, Old Norse, Proto-Indo-European, Mythology, Leda and Swan, Greek Myth, Scandinavian Myth, Milky Way, Tree of Life, Max Müller, Andrew Lang, Michael Witzel.

The Axis Mundi

Every day the sun rises in the east, ascends to the meridian, and then sets in the west. At night the moon, the planets, the stars, and the Milky Way all follow the same course. That their paths are circular appears to have been known from remote antiquity. The Greeks called this rotational motion of the heavens στρέφειν, the Latins vertere, both meaning 'to turn.' Our words tropic and vertex are derived from these ancient words, which in turn are cognate with each other and can be traced back to a common Proto-Indo-European source.

Since all circular motion is observed to revolve around a central axis, a question arises: what exists at the center of the spinning cosmos? This question has been answered variously by the different mythologies of the world, but one image that recurs repeatedly is that of a central spindle.2

In much of the ancient world, the spindle was an indispensable tool for the conversion of raw fiber into yarn. Basically, it is a weight attached to a pointed wooden shaft. The fibers are first wound onto this shaft, and then the tip of the shaft is inserted through the center of the weight, which is called a spindle whorl. This assembly can then be forcefully twisted and set in rotation, and will continue spinning like a child's top until its momentum is exhausted. While it spins, it twists raw fleece into a yarn composed of many individual strands.3

Since spindles, and all tools in the ancient world exhibiting circular motion, had wooden shafts at the central axis, early people assumed that the rotating heavens were no exception. The myths that they created typically describe a massive tree at the center of the world which acted like the axle of the spinning universe. In cultures that did not employ arboreal symbolism, this axis was conceived of as an enormous mountain, a pillar, or as a god who held up the sky. Regardless of the symbols employed, anthropologists call this mythological world-axis the "axis mundi".

Yggdrasill, the Norse Axis Mundi

In the Old Norse tradition, this axis mundi was an ash tree bearing the name, Yggdrasill. It was said to be the largest of all trees; its branches spread out over the whole world and reach up over heaven.4 A serpent or dragon lurks at its base, and two birds, an eagle and a hawk,5 perch in its branches. Two swans live in the spring beneath.6 The tree is splattered with white clay, and anything that enters the spring of water at its root becomes as white as the skin that lies within an eggshell. In Vǫluspá it is said that the tree is "moist with white dews." Three spinners, called Norns, live near the tree. They spin out the destinies of all human beings, whether for good or for ill. At the top branches, a goat nibbles the buds of the tree, and from her teats runs an inexhaustible stream of heavenly mead.

The Milky Way Galaxy

Michael Witzel was one of the first to call attention to the important significance of the Milky Way galaxy in world mythological symbols.7 He pointed out many common features in ancient religious cosmology, including the two birds that are so often described in the branches of the Tree of Life and which appear in the Ṛgveda as well as here in the Norse myths.

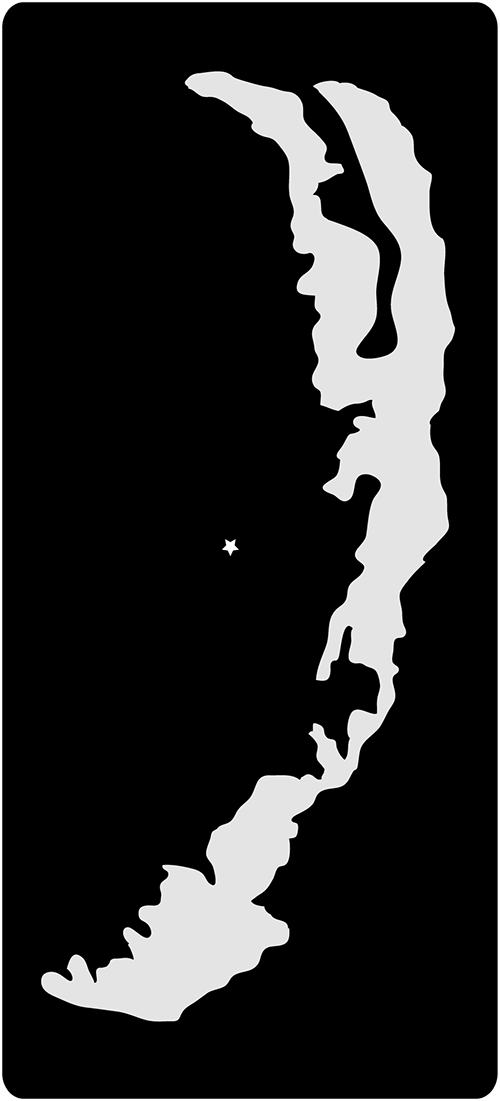

The galaxy appears as a dense band of translucent white pinpoints of light that surrounds the earth. It rises up from the horizon as a single column and then divides into two branches at mid-heaven. These branches then reach down from the zenith again to the opposite horizon, covering the entire central portion of the night sky with their brilliance. At the point where the two branches diverge from the central column, two bird asterisms are found, the constellations Cygnus, the swan, and Aquila, the eagle. The galaxy passes near the poles, and was therefore often seen as the central axle of celestial rotation, this being symbolized by the presence of the Norns who spin out human destinies. The arboreal branching form of the galaxy supported the notion that it was a tree, and its white color gave rise to the descriptions of Yggdrasill as "splattered with white clay" and "moist with white dews." Near the limits of the branches of the galaxy, as seen from the European latitudes, is the constellation Capricorn, the goat. This then corresponds to the mythical goat that eats from the highest branches of Yggdrasill. At the other end of the galaxy lies the asterism, Hydra, the serpent, which corresponds to the serpent located at the base of the celestial tree as described in the myth.8

Other parallels could be cited, but from the above it is clear that the galaxy symbolism associated with Yggdrasill is transparent. One would also expect that the name assigned to the cosmic tree would somehow be related to its important function as axis mundi. But this has not been seen to be the case.

The Traditional Etymology for "Askr Yggdrasils"

In the Eddas, the name, Yggdrasill, is almost always coupled with the word askr 'the ash tree.' The entire phrase is typically translated as "the ash, Odin's horse." Ygg is undoubtedly an epithet for Odin, as can be seen in numerous passages in the Eddas.9 The word, drasill (or an alternate form: drösull) is a poetic term meaning 'horse.'10 This is a fitting name for the World Tree—so the argument goes—because the gallows tree is sometimes referred to as a horse in Norse poetry, and because Odin was supposed to have been hanged on Yggdrasill as if on the gallows.11

Problems with the Traditional Etymology

Although this traditional etymology is widely repeated, not all authorities accept it.12 Other suggestions have included "the terrible tree" and "the yew support", neither of which have found wide acceptance. The following are some of the deficiencies in the traditional etymology:

- The texts are clear that Odin already has a horse, 'Sleipnir,' which is clearly distinct from the world-tree.13

- This traditional etymology rests on the authority of one mention alone in all of Norse Eddic literature (Hávamál 138 and 139), and that passage does not state that Odin hung on Yggdrasill, only that he hung on a windy tree.14

- It is doubtful that Yggdrasill, one of the most significant elements in ancient Norse religion, would be named for this one incident only, i.e. Odin's hanging. Such a name has nothing to do with the form, function, or characteristics of the actual tree itself.

- The connection between the axis mundi tree and the supposed etymology of its name rests on three oblique metaphors: (a) That Yggdrasill was considered a gallows tree and that it was, in fact, the tree upon which Odin hung. (b) That 'horse' is a metaphor for gallows. and (c) That 'riding a horse' is a metaphor for 'hanging from a gallows tree.' Yes, there are arguments in favor of these assumptions, but one must follow a rather tortuous path to get there.

- Old Icelandic 'drasill' is a linguistic isolate; no cognates are known in any of the other Germanic languages that signify 'horse.' Phonetically, the nearest apparent cognate is Old High German drāhsil, which does not signify 'horse' at all, but rather a person who works with spinning wooden shafts as in 'wood spinner, or wood turner.'15

- No cognates exist in any of the other Indo-European languages that are phonetically and semantically equivalent to drasill 'horse.' The common PIE term for horse is *h₁éḱwos as attested, for example, in: Latin equus, Greek hippos, Sanskrit áśva-, etc.16

- Strong evidence exists that the episode described in Hávamál 138 and 139, which is the only basis for connecting "Odin's horse" to the World Tree, Yggdrasill, is an instance where later Christian influence has entered the corpus of Norse mythology.

The myths were only first written down in the thirteenth century, two or three hundred years after the voluntary conversion of Iceland to Christianity. In the Hávamál passage, Odin describes his ordeal in the following terms, which should be compared to details from the crucifixion of Jesus as recorded in the New Testament.17

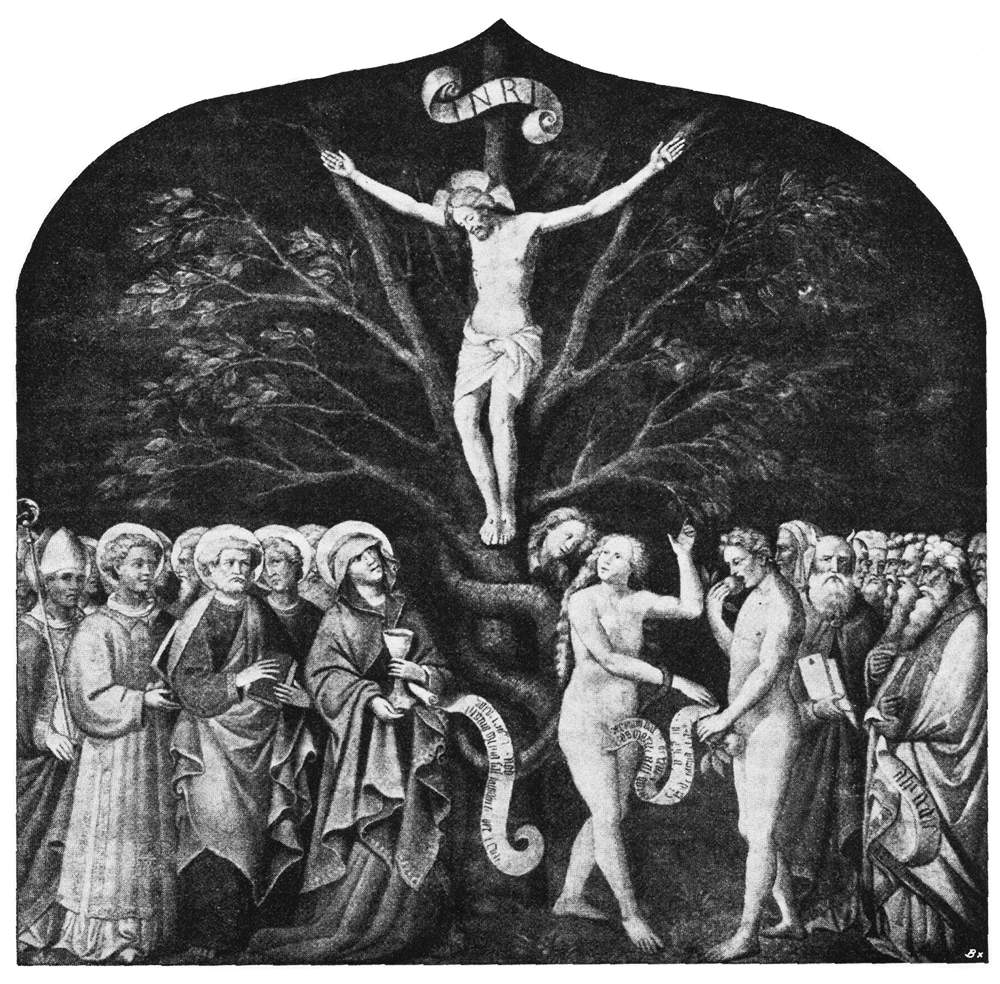

- Both die on a tree. In the stave-church portals of the late Norse period, the death of Christ was depicted as a crucifixion on a tree.18

- Both are pierced with a spear. Odin says, "wounded with a spear." The New Testament relates, "But one of the soldiers with a spear pierced his side, and forthwith came there out blood and water."19

- Both endure thirst. Odin says, "They gave me no bread, no drink from a horn." The New Testament relates, "After this, Jesus knowing that all things were now accomplished, that the scripture might be fulfilled, saith, 'I thirst.' Now there was set a vessel full of vinegar: and they filled a spunge with vinegar, and put it upon hyssop, and put it to his mouth. When Jesus therefore had received the vinegar, he said, 'It is finished': and he bowed his head, and gave up the ghost."20

- Both cry out. Odin says, "I looked below me—aloud I cried—caught up the runes, caught them up wailing, thence to the ground fell again." The New Testament relates, "And at the ninth hour Jesus cried with a loud voice, saying, Eloi, Eloi, lama sabachthani?, which is, being interpreted, My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?"21

From this comparison, it is evident that the story in Hávamál has been altered to conform to the details of the Christian crucifixion so as to make the new religion seem familiar and acceptable to the northern heathens. The unknown is how much of the story is original, and how much was changed to fit evangelical aims. Unfortunately, we do not know the answer to that question, and so the whole episode is suspect.22

A Suggestion for an Alternative Etymology

Given these problems with the traditional etymology for Yggdrasill, I offer the following alternative for consideration:

The name askr Yggdrasil(s)23 is composed of four distinct Old Norse words: askr — Ygg — dra — sill, each derived from a Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root. The first two are not controversial: askr is the ash tree, Ygg is a frequent epithet for Odin and means 'the terrifying one.'24

The next element, dra, is a reflex of PIE *terk(w) (with optional labiovelar) meaning 'twist or spin.' PIE cognates include: Latin torqueō 'twist, wind,' Old English þrǣstan 'turn, twist, writhe,' Old High German drāhsil 'roller, wood turner, wood spinner,' Old Prussian tarkue 'reins,' Old Church Slavonic trakŭ 'band, belt,' Russian tȯrok 'reins,' Albanian tjerr (<*terkne/o) 'spin,' (also tjerr 'flax yarn spun with a spindle'), Greek ἄτρακτος 'spindle,' Hittite tarku(wa)- 'turn oneself, dance,' Sanskrit tarkú 'spindle,' Tocharian B tärk- 'twist around, work wood.'25

Julius Pokorny includes, as cognate to this root, Old Icelandic þari 'seaweed.' This seems semantically odd until one recognizes the characteristic of seaweed to twist itself around other seaweed strands until a thick, strong, rope-like tangle is created.

Pokorny gives the Proto-Germanic form for this word as *þarhan-, which can be explained as the normal reflex of PIE *terk- resulting from the action of Grimm's Law:26 Initial PIE /t/ became /þ/, and final /k/ became /h/. But Proto-Germanic /h/ was lost in Old Icelandic except at the beginning of words (hence þari).27 The first syllable of the Old High German form, drāhsil, is also the expected reflex of PIE *terk. Final /k/ became /h/, and initial /t/ became /þ/, again by Grimm's Law. But then /þ/ became /d/ as a result of the High German Consonant Shift.28 So, the initial /d/ in Old High German drāhsil is expected.

The expected form in Old Icelandic, which lost /h/ but retained initial /þ/ is þra. A related word in Old Icelandic, either a reflex of PIE *terk(w) or from a closely related form *terh₁, is þraðr 'thread', from the concept, 'spun fibers.' The modern English word, thresh, is derived from the same PIE root (via Old English therscan), and has an Old Icelandic cognate, þryskva.29

Standing alone then, PIE *terk(w) would, in Old Icelandic, be þra. But in situations where an Old Icelandic word beginning with þ forms the second part of a compound (immediately following a voiced sound) it is apt to be changed into the voiced interdental fricative ð, as in Eng. the or than. And not infrequently the ð (originally þ) further changes to a /d/. This can be seen clearly in names, for example: Hall-dórr from Hall-ðórr, originally from Hall-þórr. The personal pronoun, þu, becomes du when suffixed to another word.30

Similarly, apaldr 'apple tree' is from apal-þorn.31 Professor E.V. Gordon provides a similar example where the earlier form Ragn-þórr first became Rǫgn-ðórr and then Rǫgn-dórr.32

Earlier scholarly attempts have been made to connect Old Icelandic drasill (or drǫsull) to PIE *ters- or *ter-. Sivert Hagen reports that Eiríkr Magnússon connected drasill with an Old Irish cognate (dris) that signified 'thorn bush.'33 But Magnússon himself went on to propose yet another etymology based on Latin tero that would yield the meaning, 'tearer, wearer, grinder, bruiser, sweeper.'34 The fact that scholars have repeatedly considered linking drasill to PIE roots in *ter- supports the hypothesis offered here, since PIE *ter- and *terk(w) are, phonemically speaking, nearly identical.35

The Sanskrit word, tarkú 'spindle' carries considerable weight in anchoring this reading of *terk(w) at the heart of a conservative eastern IE culture. Greek ἄτρακτος 'spindle' does the same for the center. Old High German drāhsil 'spinner, turner' is semantically close in that, while a spinner of yarn spins the shaft of the wooden spindle, the wood-turner spins a wooden shaft on his lathe. Conceptually, the two actions are strongly related, and so, I believe, provide an additional linguistic anchor in the west.

If this be granted, then we have discovered an etymological source for the first element of the compound dra-sill that fits nicely with the function of the World Tree/axis mundi of Norse religion. That the axis mundi could be viewed symbolically as a cosmic spindle is not hard to accept given the apparent rotation of the stars and the other heavenly bodies.

Further evidence that this view may be correct is provided by the myth of Er, related by Plato. Er was a warrior who had been slain in battle, but after twelve days his body was found still uncorrupted. At the moment they laid him on the funeral pyre and prepared to kindle the flame, he awakened and related to those present his experience in the other world. The story is a long one, but the essential element that is relevant to the present investigation is as follows:

But when seven days had elapsed for each group in the meadow, they were required to rise up on the eighth and journey on, and they came in four days to a spot whence they discerned, extended from above throughout the heaven and the earth, a straight light like a pillar, most nearly resembling the rainbow, but brighter and purer. To this they came after going forward a day's journey, and they saw there at the middle of the light the extremities of its fastenings stretched from heaven, for this light was the girdle of the heavens like the undergirders of triremes, holding together in like manner the entire revolving vault. And from the extremities was stretched the spindle [ἄτρακτος] of Necessity, through which all the orbits turned.36

In Plato's account the axis mundi is represented as a spindle. If our present etymological analysis is correct, the name of the Norse axis-mundi-tree contains the word spindle as the first element of a compound.

The second element, -sill, is a reflex of PIE *su̯el-, *sel- 'plank, board, wooden post.' Attested forms include: New English sill 'window sill, door sill'; Greek σέλμα, ἕλματα 'beam, planking, decking'; Old High German sūl 'pillar'; Lithuanian suolas 'bench.'37

The forms that this root exhibits in Old Icelandic are: syll, svill 'sill, door sill'38; and súl, súla 'column, pillar.' Vigfusson connects súla to Modern German Säule 'column,' Old English sýl, and Old High German sul (as in Irmin-sul).39 This last connection is important because the Irminsul was a cultic axis-mundi pillar, held sacred by the ancient Saxons, which was destroyed in the eighth century during the reign of the Emperor Charlemagne.40 We thus encounter the same word in two separate cultures denoting the post or column, believed to stand at the center of the world and to function as the cosmic axis of rotation.

It should be noted again that in the old manuscripts, the word drasill was frequently written using its alternative form: drǫsull.41 It is apparent that the vowel in the last element of this compound was somewhat fluid during the Old Norse period. Probably forms with the long vowel (súl, súla) were primary, with the alternate forms (syll, sill) being secondary via weakening.42

From the foregoing, it would seem correct to translate the phrase askr Yggdrasils as: —The Ash, Odin's Spindle Post

Why Odin's?

At the beginning of this investigation, we noted the striking correspondence between descriptions of Yggdrasill in the myth, on the one hand, and observable characteristics of the Milky Way galaxy on the other. Again, in Plato's account of Er, we encounter a description of the axis-mundi spindle that strongly evokes galaxy imagery. It was, we are told,

"a straight light like a pillar, most nearly resembling the rainbow, but brighter and purer."

Space limitations here do not permit us to survey the innumerable instances where axis-mundi characteristics in world myth parallel features of the Milky Way galaxy, but many more could be cited.43 General Germanic myth, however, provides additional information about Odin, and this may help to account for the fact that the axis-mundi spindle-tree belongs to him. This god has a large number of epithets that provide hints about his character and function in ancient religion. We have already examined Ygg, 'the fearsome one,' but another is Ýrungr, which in Old Norse signifies 'wild or stormy.'

Several compound words containing this epithet, from Old High German and Old English, are particularly illuminating. Old English Iringesweg 'Odin's Way' and Old High German Iringisstrāza 'Odin's Road' both signify the Milky Way.44 Therefore, the galaxy as axis mundi spindle post, and the galaxy as celestial pathway, both belong to Odin.

Why the Ash?

The PIE word for the ash tree, *h₃es(k) occurs in at least eight, possibly nine of the known Indo-European daughter languages. Pollen deposits and local referents reveal that two principal species were those designated as ash by PIE tribes between c 5000-3000 BC: Fraxinus excelsa and Sorbus aucuparia.45 Fraxinus excelsa is a tall tree (up to 120 feet high) with conspicuous panicles of white flowers. Sorbus Aucuparia, known widely as European Mountain Ash, or Rowan, is smaller, 20, 40, rarely 60 feet tall, also covered with showy clusters of small white flowers in spring. It thrives well in cold northern climates where hardly any other flowering tree will grow.46

Could it be that the Milky Way galaxy, with its arboreal form, its enormous size, and its myriads of densely clustered stars most closely resembled the Fraxinus excelsa with its extremely tall stature and its innumerable clusters of small white flowers? The rowan, smaller but equally profuse in flower clusters, would have stood out all the more for being the only flowering tree in the far north. Certainly, the Rowan's prominent place in northwest European folklore (as a protection against witchcraft, etc.) suggests the possibility of an ancient mythological connection.47

Axis-Mundi Associations with Horses in Indo-European Myth

The evidence cited above suggests that Old Norse drasill (or drǫsull) originally referred to the spindle post believed to exist at the center of the rotating cosmos, and that this word was inherited, either directly or via a continental borrowing, from a Proto-Germanic source. A later development, attested exclusively within Old Norse, came to associate this word with the concept 'horse' in mythological or poetic contexts.

The source of this identification most likely goes back to the ancient Indo-European tradition linking horses with the rotational motion of the heavenly bodies and thence to the axis-mundi. Elsewhere in the Norse tradition, two horses, Árvakr and Alsviðr, pull the chariot of the sun across the sky each day. Both Day and Night ride around the world every twenty-four hours in chariots pulled by horses named Skinfaxi and Hrímfaxi respectively.48 In the Vedic traditions, the Atharvaveda (19.53.1 and 11.4.22) explicitly associates the concept horse with the diurnal rotation of the heavenly bodies as represented by a chariot.49 Later Indian epic also associates the concept horse with the World Tree, which in the Bhagavadgītā, is called Aśvattha. Monier-Williams analyzes this name as a compound, the second element of which, –ttha, is derived from –stha 'stand,' so that Aśvatthá is the tree 'under which horses stand.'50 The Greek tradition also tells of horses that draw the chariot of the sun.51

These instances may well represent a PIE tradition, still practiced in the rural areas of modern Nepal, where horses were used for threshing grain. A team of horses is harnessed to a metal ring that is placed over a wooden post anchored at the center of a threshing floor. The horses are driven around and around, stamping the raw sheaves as they go, threshing out the kernels of grain. The rotation of the animals around the central axis is analogous to the rotational movement of the heavenly bodies around the axis mundi, hence the ancient association.52

Perhaps the most likely source for this motif lies in Mesopotamian astronomy where the circumpolar constellation, Cassiopeia, was seen as a horse.53 Because it lies so close to the north celestial pole, this constellation never sets and was seen in antiquity as a celestial horse that eternally runs around the pole. A portion of the Milky Way galaxy passes through Cassiopeia, providing an additional link to the notion of a horse that rotates around the axis mundi. Mesopotamian astronomy was pervasively influential in ancient times, profoundly affecting the astronomical views of many surrounding cultures.

Whatever the source, it is clear that the association of horses to the axis mundi goes back to the Indo-European common era, so that when the etymological origins of drasill had become lost, this now mysterious term was taken for a horse-referent in Old Norse. Once this mistaken association was established, the word drasill came to be employed in the poetic register as a term for horse, much as modern English employs the terms "steed, charger, or courser" to refer to that animal outside of the common vernacular usage.

Finally, in modern times, when scholars began looking for the etymological source of Old Norse Yggdrasill, they observed the poetic use of drasill signifying 'horse,' and assumed therefore that the term, Yggdrasill, meant 'Odin's horse.' This being somewhat counterintuitive, they then attempted to justify that assumption by recourse to the chain of oblique metaphors associated with the verses found in Hávamál 138 and 139.

It is interesting to note that, in the ancient Greek language, the central post of the threshing floor (as well as the celestial axis) was called the πόλος. This is the source for modern English pole, which is the current scientific term for the axis mundi.54 We have seen that Eng. thread (< 'spun fibers') and Eng. thresh (< 'rotating animals') both stem from the PIE root *terk(w) (or a closely related form *terh₁), which is the source of Old Norse dra-(sill), and which signifies spinning or rotational motion.55 It is evident that threshing, spinning, and the rotational motion of the heavens were somewhat unified concepts in the ancient Indo-European world. It is therefore not surprising that the name Yggdrasill (as axis mundi) should have somehow become associated with the horse-motif in Old Norse.

Nature Symbolism in Mythical Interpretation

Michael Witzel's pioneering study of Milky Way symbolism in world mythology (1984) and his more recent reference to these relationships in The Origins of the World's Mythologies (2012) deserve to be taken very seriously by those approaching world myth from a comparative perspective. Once the original referent of these myths is recognized by its galaxy symbolism, the remaining mythological details typically reveal themselves as coherent and transparent confirmations of the underlying mythical complex.

But the use of nature symbolism in mythical interpretation is controversial. The reasons for this are largely based on a historical misunderstanding that cries out for clarification. In order to do so, we will first consider one well-known myth that clearly illustrates the need to consider natural symbolism in order to arrive at a comprehensive understanding of its contents.

Leda and the Swan

The Greek myth of Leda and the Swan illustrates a relationship between myth and nature that is revealing. In Euripides' play Helen, Helen says,

Zeus took the feathered form of a swan, and that being pursued by an eagle, and flying for refuge to the bosom of my mother, Leda, he used this deceit to accomplish his desire upon her.56

Artistic representations of this myth typically omit the eagle that is described by Euripides, but this element is essential for a full understanding of the myth. That is because the natural referent of this story consists of an astronomical relationship between the Milky Way galaxy and two asterisms that are located at the galaxy zone of the Great Rift.

The constellation Cygnus (Swan) is located between the two branches of the galaxy, precisely at the point where the Milky Way divides (see Figure 5). So that if Leda were an archaic galaxy goddess, with the twin branches of the galaxy representing her legs, then the constellation Cygnus would be positioned directly in her lap. The constellation Aquila (Eagle) is located immediately adjacent to Cygnus, also in the area of the Great Rift.

The rape of Leda is of interest because its imagery is so unmistakably related to the galaxy. The reference here to a swan pursued by an eagle exactly parallels the position of the two constellations, Cygnus and Aquila, at the dividing point of the Great Rift, the branches of which in ancient times were sometimes seen as the legs of a celestial god or goddess.57

This discussion has employed observations about the natural world in order to make sense of a myth that is otherwise obscure. The rape of Leda by a swan consists of five mythical elements:

- Goddess (Leda)

- Swan (Zeus)

- Eagle

- Chase of swan by eagle

- Sexual violation of the goddess by swan

Natural features that correspond to the myth are:

- The portion of the Milky Way galaxy that looks like a human torso with spreading legs, and which was personified as the lap of a goddess

- The constellation Cygnus (swan)

- The constellation Aquila (eagle)

- The relative positions and order of these natural features are in conformance with the mythical chase motif: eagle—swan—personified lap (eagle chases swan into lap).

- The position of Cygnus at the location where the sexual organs would be expected if the portion of the galaxy that appears as a torso and legs were personified as the lap of a deified woman. The inference is therefore: Swan at location of female genitals = Swan copulates with female.

In addition to these observations, we have it on good authority (Hyginus, Astronomica, ii.8.1-2) that the ancients regarded the constellation Cygnus as the swan whose form Zeus took in order to perpetrate the rape of Leda. Given all of this evidence, it is hard not to conclude that this myth reflects the natural features suggested here.

But this raises a number of questions: Is there precedent for interpreting myth by appealing to natural phenomena in this way? Would drawing such conclusions be advocating a view of mythology that has long been discredited? G. S. Kirk, for example, refers to "the defunct nature-school of mythology." Mallory and Adams refer to the "defeated naturist school."58 Are these characterizations entirely accurate? Was the view that associated mythology with natural phenomena ever really defeated, as these scholars suggest?

Systems of Mythical Interpretation

Mallory and Adams (1997) describe what they consider the historical succession of significant mythological schools, along with their principal advocates:

- The Naturist School (Max Müller 1823-1900) "In the mid-nineteenth century, the major approach to comparative mythology was underpinned by the assumption that the key to interpreting myth lay with natural phenomena, especially the sun, thunder and lightning… The naturist or solar school of mythology was ultimately defeated by its own excesses… and has been generally abandoned as the primary interpretive key to IE mythology. On the other hand, that some IE mythology must relate to natural phenomena cannot be denied, especially as the few names of deities which are sufficiently widespread among the different IE stocks to posit a PIE linguistic form relate to natural phenomena such as the Sun, the Dawn, and the Sky."59

- The Ritualist School, "championed by such scholars as Sir James Frazer (1854-1941) in his Golden Bough, emphasized the close relationship between myth and ritual. Its central focus was the belief that rituals were undertaken to manipulate, largely rejuvenate, the universe and that myth was merely the narrative accompaniment to such rituals."

- The Functionalist School "[M]yths may serve to express the underlying charter for societal behavior and its construction. This approach was particularly emphasized by Emile Durkheim (1858-1917) who regarded religion as 'society personified' and the various deities or sets of deities might be seen as collective representations of the various social classes of society."

- The Structuralist School derives from the work of Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908-2009). Georges Dumézil (1898-1986) took what might be termed a 'structural-functionalist' approach to comparative IE mythology…"

- The Psychological School. "Finally, myth may be seen as an expression of the fundamental biological nature of the human mind with a potential universality that transcends boundaries of language or culture."60

There is little doubt that each of these schools has contributed to an understanding of what myth is. They represent different vectors that comprise the total set of components that make up what we might term the mythical complex.

In Essays on a Science of Mythology, Jung and Kerényi observed that the mythical complex is like a symphony that is made up of many different instruments playing simultaneously. In their metaphor, they lament the fact that mythologists (in general) have tended to focus on one specific instrument to the exclusion of all the others:61

The fact is that myths often:

- involve elements of nature symbolism.

- reflect social norms or provide charters for social behavior.

- relate to or account for religious rituals.

- express social tensions and suggest possible resolutions.

- reflect the basic physical and psychic structure of the human being.

The essential task of the mythologist, then, is to unravel these various threads and to analyze each element in order to explicate both its outward form and its latent motivation.

The "Defeat" of the Naturist School

In his book, Myth (1978), G. S. Kirk asserts that the "naturist school" or "nature-myth school" was vanquished, along with its primary proponent, Max Müller, by the scathing critique of the folklorist, Andrew Lang.

The classical attitude to myth, after being rescued by Mannhardt from Creuzer, by Andrew Lang from Max Müller, has been dominated in this century by the trends initiated by J. G. Frazer… [A]nd the idea that the motives of custom and myth in primitive societies could illuminate those of more developed cultures, including that of the ancient Greeks, became the driving force behind works of manifold learning and amazing ingenuity.62

and again:

At its best the anthropological approach brought a fresh vitality to the study of classical religion and myths, and enabled its followers to recover from the lethargy that had overtaken them once the nineteenth-century fallacies of the animists, the symbolists, the nature-myth school… had been exhaustingly laid to rest.63

Müller's Approach to Mythical Interpretation

Müller, a Sanskrit scholar who had spent much of his academic career writing on the subject of world mythology, favored an approach that saw nature symbolism as being preeminent for understanding the meaning of myths. To arrive at this underlying (and often obscure) nature symbolism, he resorted to an etymological analysis of the names of gods involved in the myths. These were very frequently the night, the dawn, and above all, the sun.

It must be said at the outset that it is misleading to refer to Müller and his colleagues as the "Naturist School" or the "Nature-Myth School" as Mallory and Adams (and G. S. Kirk) do. Müller typically referred to his approach as "Linguistic Comparative Mythology." Andrew Lang correctly uses the term, "Philological School" to describe Müller's system. These terms result from the tendency of Müller and his fellows to employ etymological analysis as their primary tool to decipher myth. In Contributions to the Science of Mythology, Müller explicitly describes his approach to the problem of mythical interpretation as the recognition of the following:

- That the different branches of the Aryan family of speech possessed before their separation not only common words, but likewise common myths;

- That what we call the gods of mythology were chiefly the agents supposed to exist behind the great phenomena of nature;

- That the names of some of these gods and heroes, common to some or to all the branches of the Aryan family of speech, and therefore much older than the Vedic or Homeric periods, constitute the most ancient and the most important material on which students of mythology have to work, and

- That the best solvent of the old riddles of mythology is to be found in an etymological analysis of the names of gods and goddesses, heroes and heroines."64

Müller had argued for a relaxation of the generally accepted rules of etymological derivation in the case of divine names. He considered these to belong to an extremely old stratum of language that had preserved earlier forms in a more or less petrified state that had resisted the otherwise prevalent linguistic changes. He claimed, for example, that the name of the Vedic god, Varuṇa, was cognate to the Greek god Ouranos and that both words could be traced back to the PIE period. And while he acknowledged that the well-established phonetic laws that described sound changes between Vedic Sanskrit and Classical Greek did not yield an exact correspondence between Varuṇa and Ouranos, still he believed them to be equivalent, especially given their similar characteristics as ancient sky gods.65

Regardless of any possible merits to this argument, the etymological license that Müller gave himself provided him with an unbounded flexibility in his determination of divine cognates. He claimed to have found Sanskrit cognates to the majority of Indo-European mythological divinities, and through an etymological analysis of those Sanskrit words, he would pronounce the meaning of the divine name and therefore the fundamental significance of the myth. The glibness by which he arrives at these correspondences, the often-implausible appearance of his etymologies, and the nearly unfailing reduction of the divinity to some type of sun-symbolism all leave the distinct impression that Müller is continually forcing the evidence to fit his pre-existing theory.

Müller had repeatedly expressed his view that mythology had arisen originally from a "disease of language." By this he meant, for example, that ancient people must have described the sun as bright, and that this adjective bright had come to be accepted, over time, as the actual name of the sun. Later, since it was assumed that a name always denotes a being, stories were invented to account for a god who lived or expressed himself through the medium of the sun. And since most words in the PIE lexicon carry grammatical gender, the sex of the gods (male or female) was taken from the grammatical gender of the words that had come to be accepted as their names. Thus, much or all of mythology could be traced back to the misapplication of language to natural phenomena.

Critique of Müller by Andrew Lang

This is precisely what Lang disputes. He states his position emphatically:

We proclaim the abundance of poetical Nature-myths; we 'disable' the hypothesis that they arise from a disease of language.66

It is chiefly to this hypothesis about the "disease of language," and to Müller's etymological emphasis, that the criticism of Andrew Lang was addressed. Lang had criticized some of these methods in a series of newspaper articles that had ridiculed what he considered some of the excesses of Müller's approach. In 1897, Müller retaliated with his Contributions to a Science of Mythology, which ran to over 800 pages in two volumes, and which repeatedly criticized Lang and his fellow members of the "anthropological school." Andrew Lang then responded with a volume of his own, Modern Mythology (1897), which although shorter in length than Müller's work, was expressly intended as a reply to it. In that book, Lang refers to the polemic between him and Müller as a "guerilla kind of warfare."

G. S. Kirk's characterization of this last publication as a decisive defeat of the mythological school championed by Müller is probably accurate. Lang's critique is an academic blitzkrieg that spares no effort to discredit Müller's arguments, his lapses in citing sources, and his faulty characterizations of both his opponents and his claimed supporters.

Although virtually everyone at the time agreed that some myths could be traced back to the Proto-Indo-European ("Aryan") period, Max Müller believed that the number of myths that could be so traced was much greater than those conceded by Lang and his group. The one case about which there was no disagreement was that the father of the gods was called in Latin Jupiter; in Greek Zeus; in Sanskrit Dyaus; etc. That all of these words are cognates of each other implied therefore that the myths about them must be so as well. Similar sets have been adduced for the sun and the dawn, for example, but much beyond these has always been disputed territory. Lang rightly criticized Müller's loose etymological methods that allowed him to expand his list of "proven" PIE myths to unreasonable lengths.

The second of Müller's four tenants above is the principle that has led to his approach being labeled the "Naturist School," but here again, the issue was always one of degree. It was not that Lang and his anthropological school of mythologists disputed the fact that many myths refer to natural phenomena, but only that Müller had succeeded in finding solar (and dawn) symbolism in the vast majority of his mythical interpretations. Nearly every mythical god analyzed by Müller was declared to be reducible to solar symbolism, and this appeared excessive in the extreme to Lang and many others. But the recognition of the general prevalence of nature symbolism in myth was never under dispute. Lang wrote, for example,

"No anthropologist, I hope, is denying that Nature-myths and Nature-gods exist. We are only fighting against the philological effort to get at the elemental phenomena which may be behind Hera, Artemis, Athene, Apollo, by means of contending etymological conjectures. We only oppose the philological attempt to account for all the features in a god's myth as manifestations of the elemental qualities denoted by a name which may mean at pleasure dawn, storm, clear air, thunder, wind, twilight, water, or what you will… Departmental divine beings of natural phenomena we find everywhere, or nearly everywhere, in company, of course, with other elements of belief—totemism, worship of spirits, perhaps with monotheism in the background. That is as much our opinion as Mr. Max Müller's. What we are opposing is the theory of disease of language, and the attempt to explain, by philological conjectures, gods and heroes whose obscure names are the only sources of information."67

The Nature-Myth School Was Never Defeated

From this discussion it can be seen that the anthropological school that Lang represented did not defeat the nature-myth school, rather it defeated the philological school of mythologizing that had been championed by Max Müller.

- Myth did not arise out of a "disease of language."

- The etymological methods employed by Müller were mostly inadequate and resulted in gross errors.

- The sun, although it did figure as a central element in some myths, was not the mythological focus to any degree that it was considered to be so by Müller.

Lang did rightfully put these misconceptions to rest.

But while interpretations of myth based on natural phenomena have fallen somewhat out of fashion in recent years, they have never been shown to be a priori fallacious. They have never been "defeated," nor can they honestly be characterized as "defunct." Although Andrew Lang may correctly be said to have demolished the "philological conjectures" of Max Müller, he never challenged the claim that much of mythology can be explained by reference to natural features. On the contrary, he acknowledged that this is very widely and correctly seen to be the case.

The conclusions offered above concerning Leda as a galaxy goddess in her interaction with Zeus stand as a paradigmatic example of how myth can be meaningfully interpreted by reference to natural phenomena. Probably this story served as a mnemonic device for sailors who relied on the stars for navigational purposes, and who must, therefore, recognize the orientation of the constellations despite their ever-changing diurnal motion. In this respect, the Milky Way Galaxy has traditionally provided the surest and quickest guide to the positions of the stars.

Such an example as this would argue for a fresh evaluation and renewed appreciation for the use of nature symbolism as one valuable approach to be employed in the comparative interpretation of world myth.

Leda and the Swan: A Deeper Look

Myth is rarely one-dimensional. The story of Leda and the Swan carries multiple meanings, none of which negates the other. The following may stand as an initial attempt to summarize its various levels of meaning:

- As described above, it provided mnemonic material for a comprehensive mental map of the stars, probably primarily for navigational purposes.

- It provided moral guidance to young women. Zeus was forced to employ deception because, "Proper girls do not give themselves to men who lust after them outside of socially-sanctioned marriage." This is an example of the social tensions that arise from the fact that men are typically less discriminating about who they mate with, whereas women must consider the long-term well-being of themselves and their offspring.

- It provided a warning to young women concerning the devious stratagems that men will employ in order to have their way with them.

- It provided a charter for the behavior of kings (represented by Zeus), who consider themselves above the normal constraints of law and morality.

- It provided a mythico-historical antecedent for Helen, the child of Leda by Zeus, who was herself originally a mythical tree-goddess. The branching pattern of the galaxy at the Great Rift was often viewed as the branching of a celestial tree, an alternative to the anthropomorphized legs or outstretched arms of a god or goddess.

- It provided the "narrative accompaniment" for the rituals and dances performed in Sparta in Helen's honor as a tree-nymph, and for whatever rituals that were associated with the egg that was said to have been laid by Leda as a result of her impregnation by Zeus, and which hung be-ribboned from the roof of the Sanctuary of Hilaeira and Phoibe.68 Helen was said to have hatched from that egg.69

- It provided the back-story to the Homeric epic, where Helen was the cause of the Trojan War and of all the sufferings that the Greeks endured for her sake. This is an example of how myth can be used to justify historical events such as wars. Its implicit claim is that the Greeks did not attack Troy in order to gain control of the trade routes into the Black Sea, but rather they did so to righteously avenge the illegal and immoral abduction of the Spartan princess, Helen, daughter of Zeus and Leda.

- Because of its vaguely anthropomorphic appearance, its shining luster, and its celestial location, the Milky Way Galaxy served as the physical referent for many of the gods and goddesses of the ancient world. This identification was typically considered an esoteric secret, known only by those who had been initiated into the mysteries, and therefore speaking about such matters directly and openly was prohibited. It was, however, permitted to allude to them indirectly by way of hints and clues as long as these were not too obvious. The myth of Leda and the Swan provides just such a combination of veiled allusions that would be obscure to the masses, but that were obvious to those who knew the secret.

It is evident from the above that myth is multi-faceted, and that no single methodological approach is adequate to encompass its breadth. This is perhaps a key to the fascination that mythology has exerted throughout the ages and why we continue to concern ourselves with stories that were told two and a half millennia in the past. An important part of the total mythical complex includes the component involved with natural phenomena, and this is often represented symbolically. We would do well to acknowledge and to weigh carefully all available evidence in order to arrive at the most comprehensive understanding possible of these ancient mythical narratives.

References

Andrén, Anders. Tracing Old Norse Cosmology. Lund: Nordic Academic Press, 2014.

Apollodorus. The Library. vol. 2. James Frazer, trans. Cambridge: Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, 2002 (first published 1921).

Bhagavadgītā in the Mahābhārata. J. A. B. van Buitenen, trans. and ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981.

Bailey, L. H. Standard Cyclopedia of Horticulture. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1935.

Bosworth, Joseph and T. Northcote Toller. Anglo-Saxon Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1921.

Cleasby, Richard and Gudbrand Vigfusson. Icelandic – English Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1874.

Crossley-Holand, Kevin. The Norse Myths. New York: Pantheon Books, 1980.

Davidson, H. R. Ellis. Gods and Myths of Northern Europe. New York: Penguin, 1964.

De Vries, Jan. Altnordisches etymologisches Wörterbuch. 2nd edition. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1977.

Egilsson, Sveinbjörn. Lexicon Poëticum Antiquæ Linguæ Septentrionalis. Hafniæ: Societas Regia Antiquariorum Septentrionalium, 1860.

Euripides. Helen. in Euripides: The Bacchae and Other Plays. Vellacott, Philip, trans., New York: Penguin, 1973 (first published 1954).

Euripides. Helen. Arthur Sanders Way, trans. Cambridge: Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, 1988.

Fortson, Benjamin W. Indo-European Language and Culture. 2nd ed., Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

Friedrich, Paul. The Meaning of Aphrodite. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1978.

Gimbutas, Marija. The Language of the Goddess. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1989.

Gordon, E. V. An Introduction to Old Norse. 2nd ed., rev. A. R. Taylor. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1957.

Grimm, Jacob. Teutonic Mythology. vol. 2. London: George Bell and Sons, 1883.

Haynes, Gregory. Tree of Life, Mythical Archetype. Foreword by Michael Witzel. San Francisco: Symbolon Press, 2009.

———. "Resonant Variation in Proto-Indo-European." Mother Tongue 22. 2020. https://www.mother-tongue-journal.org/MT/mt22.pdf, 151-222.

Hagen, Sivert N. "The Origin and Meaning of the Name Yggdrasill." Modern Philology. vol. 1, No. 1. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1903. https://www.jstor.org/stable/432424.

Hesiod, Homeric Hymns, Epic Cycle, Homerica. Hugh G. Evelyn-White, trans. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Loeb Classical Library 57, Harvard University Press, 2002.

Holy Bible. Authorized Version (AV).

Hunger, Hermann and David Pingree. Astral Sciences in Mesopotamia. Leiden, Boston, Köln: Brill, 1999.

Hyginus, Astronomica. Bk 2. The Myths of Hyginus, translated and edited by Mary Grant. University of Kansas Publications in Humanistic Studies, no. 34. https://topostext.org/work/207.

Jurewicz, Joanna. "The wheel of time: How abstract concepts emerge (a study based on early Sanskrit texts)." Public Journal of Semiotics 8 (2). https://journals.lub.lu.se/pjos/article/view/19983/18025.

Jung, C. G., and Carl Kerényi. Essays on a Science of Mythology. R. F. C. Hull, trans. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1969.

Kellogg, Robert. A Concordance to Eddic Poetry. Colleagues Press, 1988.

Kirk, G. S. Myth: Its Meaning and Functions in Ancient and Other Cultures. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: Cambridge University Press and University of California Press, 1970.

Kluge, Friedrich. Etymologisches Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache. Berlin: Walter De Gruyter & Co., 1963.

Krause, Arnulf. Reclams Lexikon der germanischen Mythologie und Heldensage. Stuttgart: Philipp Reclam, 2010.

Lang, Andrew, Modern Mythology. London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1897.

Liddell, Henry George, Robert Scott, and Henry Stuart Jones. A Greek–English Lexicon. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968.

Magnússon, Eiríkr. Odin's Horse Yggdrasill. "A Paper read before the Cambridge Philological Society January 24, 1895." Oxford, 1895.

Mallory, J. P. and D. Q. Adams. The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Mallory, J. P. and D. Q. Adams, eds. The Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture (EIEC). London: Fitzroy Dearborn, 1997.

Monier-Williams, Sir Monier. A Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1889.

Müller, Max. Contributions to the Science of Mythology. London, New York, and Bombay: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1897.

Noreen, Adolf. Altisländische und altnorwegische Grammatik. 4th ed. Halle: Niemeyer, 1923.

Oxford Classical Dictionary. Max Cary, Herbert J. Rose, H. Paul Harvey, and Alexander Souter, eds. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1964.

Pausanius. Guide to Greece. Peter Levi, translator. New York: Penguin, 1985.

Plato. The Republic. Paul Shorey, translator. The Collected Dialogues of Plato. Hamilton and Cairns, eds. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1961.

Poetic Edda. Carolyne Larrington, trans. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Poetic Edda. Lee Hollander, trans. 2nd edition, revised. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1962.

Poetic Edda (Poems of the Elder Edda). Patricia Terry, trans., rev. ed. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1990.

Pokorny, Julius. Indo-germanisches etymologisches Wörterbuch (IEW). vol. 1. Bern: Francke Verlag, 1959.

Puhvel, Jaan. Comparative Mythology. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1987.

Ringe, Don. From Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Rix, Helmut, et al. Lexicon der indogermanischen Verben (LIV). Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag, 2001.

Sauvé, James. "The Divine Victim." in Myth and Law among the Indo-Europeans. Jaan Puhvel, ed. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1970.

Simek, Rudolf. Lexicon der germanischen Mythologie. 3rd edition. Stuttgart: Alfred Kröner Verlag, 2006.

Sturluson, Snorri. The Prose Edda. Jean Young, trans. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1954.

Sturluson, Snorri. The Prose Edda. Jesse L. Byock, trans. London: Penguin Books, 2005.

Sturluson, Snorri. The Prose Edda. Arthur Gilchrist Brodeur, translator. New York: The American-Scandinavian Foundation, 1929.

Times Atlas of the World: Comprehensive Edition. Times Books, 1983.

Witzel, Michael. "Sur le chemin du ciel." Bulletin des Etudes Indiennes 2 (1984). http://www.people.fas.harvard.edu/~witzel/CheminDuCiel.pdf.

———. The Origins of the World's Mythologies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Notes

1 Correspondence can be addressed to the author at [email protected]. An earlier version of the first part of this paper (Yggdrasill) was presented by the author at a conference (Myth, Language, and Prehistory: A Celebratory Conference in Honor of Prof. Michael Witzel), which was held at Harvard University on September 6-8, 2019. ↩

2 By way of extension from "spinning," the concept "weaving" is sometimes also employed in myth to symbolize the axis-mundi rotation of the stars. This is because spinning is such a large component of the over-all weaving process. ↩

3 Clay spindle whorls (tarkupiṇḍa) have been found in Europe from the 6th to 5th millennia BC, indicating that spinning was known at least by that time, although the earlier use of (perishable) wooden spindle whorls is probable. See Gimbutas, Language of the Goddess, 67. ↩

4 Sturluson, Prose Edda, trans. Young, 42-46. ↩

5 Prose Edda, trans. Young, 45. ↩

6 Prose Edda, trans. Young, 46. ↩

7 Witzel, "Sur le chemin du ciel," 213-279; Witzel, The Origins of the World's Mythologies, 133, 135. For a detailed comparative study of the Tree of Life myth and its Milky Way symbolism, see Haynes, Tree of Life, Mythical Archetype (Foreword contributed by Michael Witzel). ↩

8 For a precise depiction of the Milky Way galaxy and its neighboring asterisms, see Times Atlas of the World, xxviii-xxix; Compare Haynes, Tree of Life, Mythical Archetype, 119. ↩

9 deVries, Altnordisches etymologisches Wörterbuch, s.v. "yggr," 677; Vǫluspá 28, 29, in Poetic Edda, trans. Hollander, 6, 64. ↩

10 For drasill, see deVries, Altnordisches etymologisches Wörterbuch, s.v. "drasill," 81; Egilsson, Lexicon Poëticum, s.vv. "DRASILL, DRÖSULL," 104, 109; Kellogg, Concordance to Eddic Poetry, s.v. "drasill," 69. Kellogg cites Atlakviða st. 4 and 32 as examples of drasill in the texts. In st. 4, "dafar darraðar, drösla mélgreypa," which Larrington translates, "lances with pennants, coursers gnashing at their bits." In st. 32, "dynr var í garði, dröslum of þrungit," which Larrington translates, "There was a noise in the courtyard, crowded with horses." See Poetic Edda, trans. Larrington, 211, 215. ↩

11 For the traditional etymology, see Poetic Edda, trans. Hollander, 4n16, 36n67; Poems of the Elder Edda, trans. Terry, 9; and Sturluson, Prose Edda, trans. Byock, 120. For the episode of Odin's hanging on Yggdrasill, see Poetic Edda, Hávamál 138-139, trans. Hollander, 36; see also Krause, Reclams Lexikon, s.v. "Yggdrasill," 317; Crossley-Holand, The Norse Myths, 187; Puhvel, Comparative Mythology, 194. ↩

12 For doubts about the traditional etymology, see Sturluson, Prose Edda, trans. Brodeur, 266; Andrén, Tracing Old Norse Cosmology, 28; deVries, Altnordisches etymologisches Wörterbuch, s.v. "Yggdrasill," 676; Simek, Lexicon der germanischen Mythologie, s.v. "Yggdrasill," 494-96; Davidson, Gods and Myths of Northern Europe, 194; and Hagen, "The Origin and Meaning of the Name Yggdrasill," 57-69. ↩

13 For Sleipnir, see Grimnismál 45; Baldrs draumar 2; Voluspá hin skamma 13; Sigrdrifumál 17. All references are to Poetic Edda, trans. Hollander; In Sturluson, Prose Edda, trans. Brodeur, see The Beguiling of Gylfi XLI, 53. ↩

14 Poetic Edda, Hávamál 138 and 139, trans. Hollander, 36; see also Magnússon, Odin's Horse Yggdrasill, 21. ↩

15 Pokorny, IEW, s.v. "*terk," 1077; Kluge, Etymologisches Wörterbuch, s.v. "drechseln," 141. ↩

16 Mallory and Adams, Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European, 139. ↩

17 Andrén, Tracing Old Norse Cosmology, 14-17. ↩

18 Haynes, Tree of Life, Mythical Archetype, 74-79. ↩

19 John 19:34 (Authorized Version). ↩

20 John 19:28-30 (AV). ↩

21 Mark 15:34 (AV). ↩

22 Sophus Bugge (1881—9:399 ff.) cited in Andrén, Tracing Old Norse Cosmology, 35. Bugge was one of the first to call attention to the problem of Christian contamination of the Norse myths; cf. Hagen, Origin and Meaning of the Name Yggdrasill, 62; See also Magnússon, Odin's Horse Yggdrasill, 17, 27; Compare the episode where Zeus hangs Hera from Olympus by golden bracelets. See Haynes, Tree of Life, Mythical Archetype, 207. ↩

23 The (s) is the Old Norse "genitive of identity." See Gordon, An Introduction to Old Norse, 310: "In addition to the ordinary possessive use, there was a commonly employed gen. of specification (of amount or identity): ...Yggdrasils askr 'the ash Yggdrasil'." ↩

24 Mallory and Adams, EIEC, s.v. "trees," 599; deVries, Altnordisches etymologisches Wörterbuch, s.vv. "askr," "ugð," and "agi," 15, 632, 3; Egilsson, Lexicon Poëticum, s.v. "UGGR," 830. ↩

25 Mallory and Adams, EIEC, s.v. "textile preparation," 572. Note that Mallory and Adams use the notation /w/ to signify the sound typically written /u̯/ in the linguistic literature. The authorities vary in their analysis of this root: Mallory and Adams *terk(w); Rix *terku̯; Pokorny *terk. ↩

26 For the development of PIE into Proto-Germanic, see Ringe, From Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic. ↩

27 Gordon, An Introduction to Old Norse, 279: "h remained only at the beginning of a word. In other positions h disappeared." This process can also be seen, for example, in the change from PIE *spek̑ 'to see, to spy out' as in Eng. spectacles, spectator, inspect, etc. Its reflex in Old High German is spehōn, and in Old Icelandic spā 'to see the future, to prophesy' as in Old Icelandic Vǫluspá 'the visions of the prophetess.' ↩

28 Fortson, Indo-European Language and Culture, 366: "High German is also characterized by the shift of West Germanic *d to t and *þ to d: compare Eng. deed with German Tat and Eng. thing with German Ding." ↩

29 Pokorny calls *terk- 1077 an extension of *ter- 1071 (modern form *terh₁-). Indeed, both are semantically equal. PIE *terk(w)- is more about spinning and spindles, whereas *terh₁-, in addition to spinning includes the concept of boring, drilling, or threshing. But since nearly all ancient boring and drilling were performed with a friction stick rotated by means of a bow with a string under tension (like the primitive fire-drill), the concept of spinning (either fiber or friction stick) is central to both actions. Threshing was typically done by leading animals in rotational motion (turning) around a threshing floor. See note 53 infra. ↩

30 Cleasby-Vigfusson, Icelandic–English Dictionary, s.v. "þ," 729; Noreen, Altisländische und altnorwegische Grammatik, 161. ↩

31 Cleasby-Vigfusson, Old Icelandic—English Dictionary, s.v. "apaldr," 22 ↩

32 Gordon, An Introduction to Old Norse, 267. ↩

33 Related in Magnússon, Odin's Horse Yggdrasill, 59; also mentioned in Hagen, The Origin and Meaning of the Name Yggdrasill, 61. ↩

34 Magnússon, Odin's Horse Yggdrasill, 59-60. ↩

35 One cannot completely rule out the possibility of a continental borrowing (e.g., from Old Saxon or Old High German) where a form similar to OHG drāhsil came into Old Norse with the initial /d/ already present. Joseph C. Harris, personal communication. ↩

36 Plato, The Republic, Book 10:614b, trans. Paul Shorey, 839-840 (Emphasis added). ↩

37 Mallory and Adams, The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European, 227; Mallory and Adams, EIEC, s.v. "plank," 431; and Pokorny IEW 2*sel-, *su̯el- 898. ↩

38 deVries, Altnordisches etymologisches Wörterbuch, s.v. "syll," 573; Cleasby-Vigfusson, Old Icelandic—English Dictionary, s.v. "syll," 614. ↩

39 deVries, Altnordisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch, s.v. "súl," 560; Cleasby-Vigfusson, Old Icelandic—English Dictionary, s.v. "súla, súl," 605. ↩

40 For the Irminsul, see Puhvel, Comparative Mythology, 200; Witzel, Origins of the World's Mythologies, 72, 135; Grimm, Teutonic Mythology, 799. ↩

41 deVries, Altnordisches etymologisches Wörterbuch, s.v. "drǫsull," 86; Egilsson, Lexicon Poëticum, s.v. "DRÖSULL," 109. ↩

42 Joseph C. Harris, Professor Emeritus, Harvard University, personal communication. ↩

43 For a more extensive listing, see Haynes, Tree of Life, Mythical Archetype. ↩

44 deVries, Altnordisches etymologisches Wörterbuch, s.v. "Ýrungr," 680. ↩

45 Mallory and Adams, EIEC, s.v. "Trees," 599-601. ↩

46 Bailey, Standard Cyclopedia of Horticulture, s.vv. "Fraxinus" and "Sorbus," 1274-76, 3194-95. ↩

47 Sturluson, Prose Edda, trans. Young, 107. ↩

48 Gylfaginning in Sturluson, The Prose Edda, trans. Young, 38. ↩

49 Jurewicz, The wheel of time. ↩

50 The Bhagavadgītā in the Mahābhārata, 37[15].1, 129; Monier-Williams, A Sanskrit-English Dictionary, s.v. "Aśvatthá," 115; Sauvé, "The Divine Victim," 187. ↩

51 Homeric Hymns, XXVII.14 and XXXI.14, in Hesiod, Homeric Hymns, Epic Cycle, Homerica, 455, 459. ↩

52 For an example of this practice, see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5TERz4ohZfk ↩

53 Hunger and Pingree, Astral Sciences in Mesopotamia, 60, 273. ↩

54 Liddell, Scott, and Jones, A Greek–English Lexicon, 1436, s.v. "πόλος." ↩

55 For an analysis of PIE *terk(w)- and *ter(h₁)-, demonstrating their common underlying semantic value "rotational motion," see Haynes, "Resonant Variation in Proto-Indo-European," 151-222. ↩

56 Euripides, Helen, in Euripides: The Bacchae and Other Plays, Vellacott, Philip, trans., 136. Arthur Sanders Way (Loeb Classical Library, vol. 1, 466-69) gives an alternate translation. See also: Hyginus, Astronomica ii.8.1-2. ↩

57 For a precise depiction of the Milky Way Galaxy and its neighboring asterisms, see The Times Atlas of the World, xxviii-xxix; Compare: Haynes, Tree of Life, Mythical Archetype, 119. ↩

58 Kirk, Myth, 90; Mallory and Adams, EIEC, 116-17. ↩

59 Characterizations of the schools of myth-interpretation are quoted from Mallory and Adams, EIEC, 116-23. ↩

60 Kirk, Myth, 275 ↩

61 Jung and Kerényi, Essays on a Science of Mythology, 16–17, 92. ↩

62 Kirk, Myth, 2-3 ↩

63 Kirk, Myth, 3. For a brief discussion of the Müller-Lang controversy, and for an opposing view on some of the more modern approaches to mythological interpretation, see Friedrich, The Meaning of Aphrodite, 30-31. ↩

64 Müller, Contributions to the Science of Mythology, 21. ↩

65 Müller, Contributions to the Science of Mythology, 416. ↩

66 Lang, Modern Mythology, 135. ↩

67 Lang, Modern Mythology, 133 ↩

68 Mallory and Adams, EIEC, 164. ↩

69 Pausanius, Guide to Greece, Levi, trans., vol. 2, 26n42, 28n45, 54, 70; Apollodorus, The Library, vol. 2, 25; and Euripides, Helen, Vellacott, trans., 143. ↩