The Dene-Caucasian Macrofamily:

Lexicostatistical Classification and Homeland

Abstract

To test the competing theories about the structure of the Dene-Caucasian (DC) macrofamily, the matrix of lexical matches between 42 extant and reconstructed DC languages (Basque, Burushaski, Yeniseian, Northwest Caucasian, eight Northeast Caucasian, 27 Sino-Tibetan, three Na-Dene) and 39 other languages, based on short (50-item) wordlists from The Tower of Babel: The Global Lexicostatistical Database, compiled by G. S. Starostin, A. S. Kassian, and M. A. Zhivlov, was subjected to several multivariate analyses. Rooted networks were constructed, and the quasi-spatial model, which had rarely been used in lexicostatistics, was applied. Results support G. Starostin et al.'s classification while revealing certain details that went unnoticed under a strictly genealogical approach. Basque is connected with Northeast Caucasian, specifically proto-Nakh, not only genealogically but by areal ties as well. The Yeniseian-Burushaski clade appears to have had areal connections with Altaic. Na-Dene may be a Sprachbund rather than a clade. Based on geographic and genetic considerations, especially the distribution of the autosomal component ANE, the DC homeland, like that of Eurasian languages, was located in Southern Siberia or Eastern Kazakhstan. Moreover, the filial branches of both macrofamilies expanded along the same four principal routes: western (toward Caucasus, Anatolia and, in the case of DC, further west into Europe), northern (into the Siberian taiga), northeastern (toward Beringia), and eastern (toward northeastern China). The totality of genetic, craniological and archaeological facts suggests that among the DC speakers were the Okunev and the Karasuk people. Their probable affiliation was Yeniseian, but the relic Okunev population may have been collaterally related also to other DC groups such as Na-Dene and Sino-Tibetan.

Keywords: Lexicostatistics, Dene-Caucasian Macrofamily, Basque, Burushaski, North Caucasian, Yeniseian, Sino-Tibetan, Na-Dene, population genetics.

Introduction

The idea of the Dene-Caucasian (hereafter DC) macrofamily results from the generalization of several theories. The key hypothesis, Sino-Caucasian in its modern version, was formulated by S. A. Starostin (1984), who adduced facts indicating deep affinity of North Caucasian with Yeniseian and Sino-Tibetan. Then he put forward arguments suggesting that Burushaski, which he believed to be closest to Yeniseian, belongs to the same macrofamily (S. Starostin 2005: 69); earlier, the same conclusion was reached by V. N. Toporov (1971), Blažek & Bengtson (1995), and G. van Driem (2001: 1186–1205). S. L. Nikolaev (1991) linked North Caucasian to Na-Dene, and E. Vajda (2010) believes Na-Dene to be akin to Yeniseian. This completed the hypothesis of the Dene-Caucasian macrofamily (hereafter DCM), which includes Sino-Caucasian (Starostin G. 2012). J. D. Bengtson (2017) has done much to demonstrate that one of the DC languages is Basque, which is closest to North Caucasian.

This article is authored by a non-linguist. Being unable to assess the validity of DCM, my conclusions should be taken in the subjunctive: if DCM were a monophyletic taxon, what would the implications be? The study has two objectives. First, I apply the models, which had rarely been used in lexicostatistics, to DC languages from The Global Lexicostatistical Database by G. S. Starostin, A. S. Kassian, and M. A. Zhivlov (The Tower of Babel: The Global Lexicostatistical Database. http://starling.rinet.ru/new100/trees.htm, last accessed 15 April, 2022).1 The second goal is to discuss certain extralinguistic facts relevant to the issue of the DC homeland and migrations, provided, to reiterate, DCM proves real.

Languages, Models, and Methods

The following extant and reconstructed languages belonging to DCM (42) and to other macrofamilies (39), listed in alphabetical order, were used: Altaic (JAP – Japonic, KOR – Korean, MNG – Mongolic, TNG – Tungusic, TRC – Turkic), Basque (BSQ), Burushaski (BUR), Chukotko-Kamchatkan (CHK – Chukchee, ITL – Itelmen), Dravidian (BRA – Brahui, GND – Gondwan, KOG – Kolami-Gadba, NDR – North Dravidian, SDR – South Dravidian, TEL – Telugu), Eskaleut (ALE – Aleut, INU – Inuit, YUP – Yupik), Indo-European (ALB – Albanian, ARM – Armenian, BLT – Baltic, CLT – Celtic, GRK – Greek, GRM – Germanic, HIT – Hittite, IRA – Iranian, LAT – Latin, SKR – Old Indian, SLV – Slavic, TKH – Tokharian), Kartvelian (KRT – Narrow Kartvelian, SVA – Svan), Na-Dene (ATH – Athabascan, EYA – Eyak, TLI – Tlingit), Northeast Caucasian (AND – Andic, AVA – Avar, CEZ – Cezic, DRG – Dargwa, KHI – Khinalug, LAK – Lak, LZG – Lezghian, NKH – Nakh), Northwest Caucasian (WCA), Sino-Tibetan (BGA – Bodo-Garo, CHN – Old Chinese, DHI – Dhimal, DIG – Digaro, HRU – Hrusish, JIA – Jiarongic, JPH – Jingpho, KAR – Karen, KHA – Kham, KIR – Kiranti, KNY – Konyak, KUK – Kuki-Chin, LEP – Lepcha, LOL – Lolo-Burmese, MAG – Magar, MEI – Meithei, MIK – Mikir, NAG – Naga (Kuki-Chin-Naga group), NUN – Nungish, QNG – Qiang, SHL – Sherdukpen-Sulung, TIB – Tibetic, TMG – Tamang-Gurung, TNI – Tani, TSH – Tshangla, TUJ – Tujia, WHM – West Himalayan), Uralic (BFN – Baltic Finnic, HNG – Hungarian, MAR – Mari, MRD – Mordvinic, OUG – Ob-Ugric, PRM – Permic, SAM – Samoyed, SMI – Saami), Yeniseian (YEN), Yukaghir (YUK).

Models mentioned above were already used in my previous studies focusing on three families: Indo-European (Kozintsev 2018a,b, 2019a,b), Eurasiatic, or Narrow Nostratic (Kozintsev 2020a), and Afroasiatic (Kozintsev 2021а; Kozintsev, Militarev 2022). Under the mixed genealogical-areal model, rooted networks were constructed.2 Under the quasi-areal model, which is akin to J. Schmidt's Wave Theory, the matrix of pairwise lexical matches was subjected to nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS), and the minimum spanning tree (MST) was drawn, showing the shortest path connecting points in the multivariate space.3

When extant and extinct languages are processed simultaneously under the genealogical approach, a problem arises, which in modern glottochronology is solved with the help of corrections (Burlak & Starostin 2005: 142).4 Because the methods employed here are not based on glottochronological postulates, raw data were used.

Classification

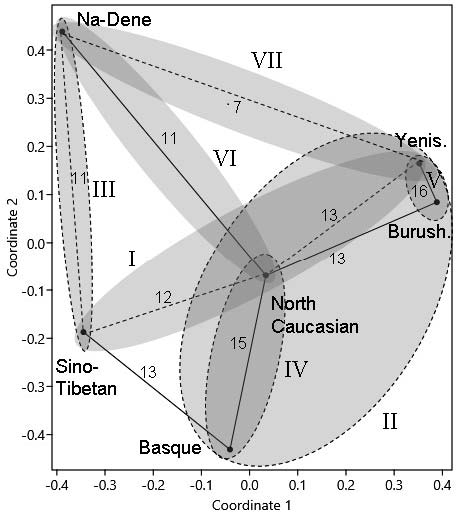

Let us first examine the two-dimensional projection of DC languages at the level of families and isolated languages (Fig. 1). As the minimum spanning tree shows, the North Caucasian family takes a central position. MST edges connect it with three DCM members: Basque, Burushaski, and Na-Dene. The strongest links are those between Yeniseian and Burushaski (group V – central), and between North Caucasian and Basque (group IV – western). The eastern group (III), consisting of Sino-Tibetan and Na-Dene, is less certain, and the link connecting Na-Dene with Yeniseian is the weakest. Nearly all DCM subgroups are dealt with by various theories (see caption to Fig. 1). To my knowledge, only the connection between Sino-Tibetan and Basque (in fact, no weaker than those linking North Caucasian with Yeniseian and Burushaski) has never been discussed, evidently because of its striking disagreement with geography.

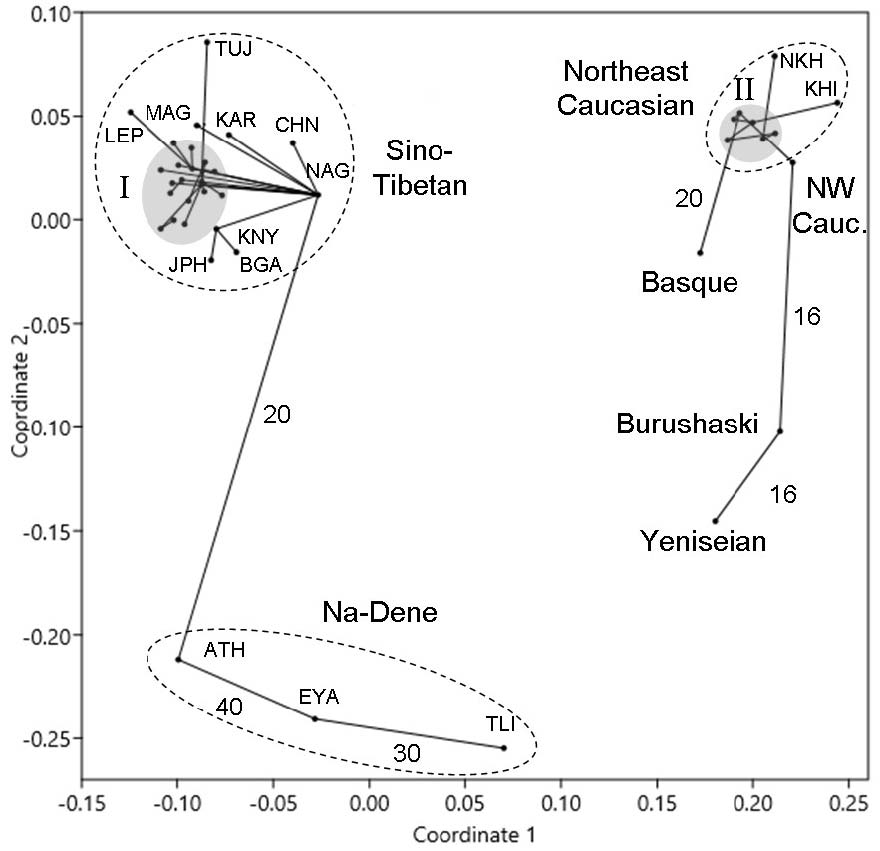

Let us now look at the two-dimensional projection of the multivariate arrangement of separate DC languages (Fig. 2). The MST method must connect all points most parsimoniously. But the edge connecting Sino-Tibetan with North Caucasian is a very weak link between Magar and Nakh (6%). Given the huge geographic distance between them, the connection must be deemed incidental, the more so because at the higher taxonomic level (Fig. 1) the same method connects Sino-Tibetan with Basque rather than with North Caucasian.

Other ties between separate languages of various DC families are markedly stronger than those between families themselves (Fig. 1), which is also due to random fluctuations. Within the Sino-Tibetan family, we note an unusually high number of edges connecting Naga (of the Kuki-Chin-Naga group) with other languages – nine (see below). Naga is also linked with Athabascan (20% of matches), but another Na-Dene language, Tlingit, has only 9% matches with Naga. Within the Na-Dene family, too, the structure of ties is somewhat anomalous: Athabascan and Eyak have 40% of lexical matches, Eyak and Tlingit, 30%, whereas Athabascan and Tlingit are much less similar (17%). The Na-Dene family, therefore, appears to be heterogeneous, which is mirrored by its marked stretch in the two-dimensional projection (Fig. 2).

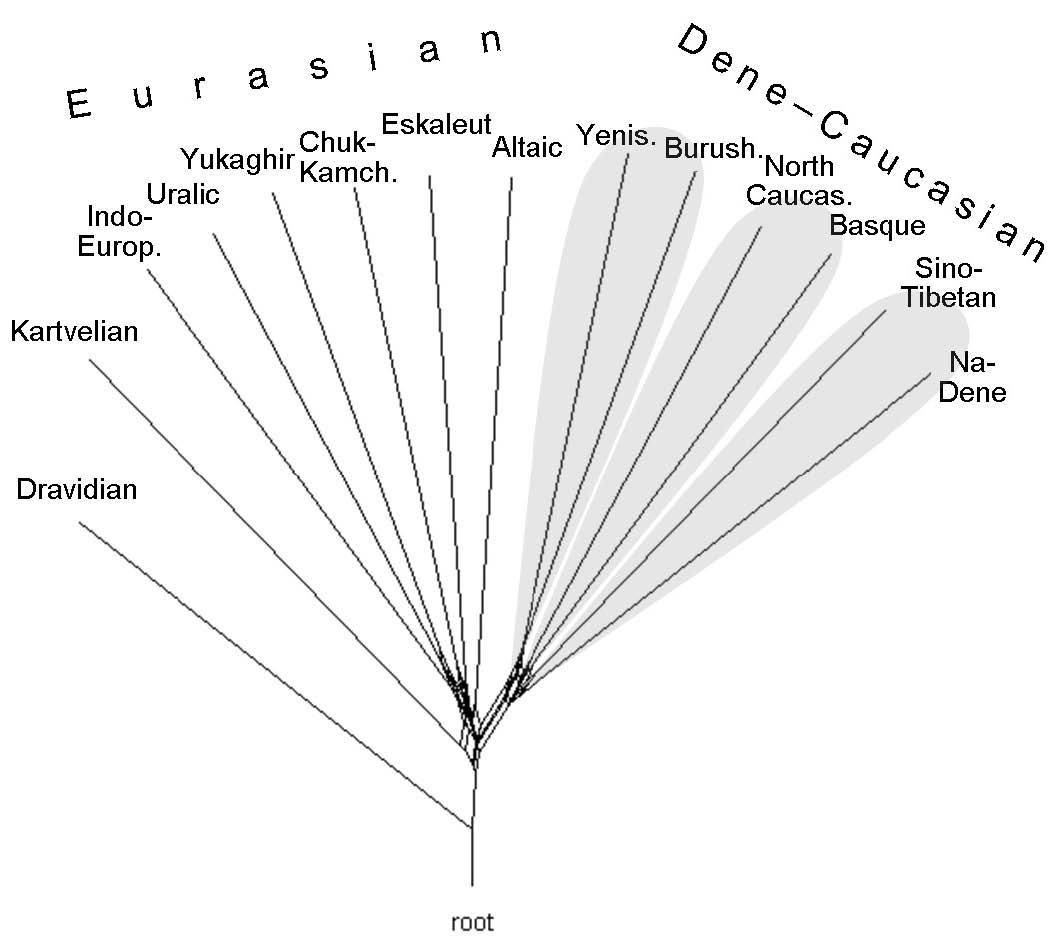

The network of families and isolated languages, rooted by Dravidian5 (Fig. 3), shows that the DCM is a no less distinct unity than Eurasian, let alone Macro-Nostratic, which has traditionally included also Kartvelian, Dravidian, and even Afroasiatic. In the graph, DCM appears to be a bona fide monophyletic taxon6 opposed to Eurasiatic. Within DCM, three pairs are seen, corresponding to hypothetic groups in Fig. 1. The geographically central pair, consisting of Yeniseian and Burushaski (V), is a clade; the western pair, Basque and North Caucasian (IV) may be a clade too. Whether the eastern pair, Sino-Tibetan and Na-Dene (III), form a clade is unclear, maybe because their presumed common ancestor was very ancient and maybe because genetic ties in this case are blurred by areal contacts, shown by "collaterals" at the base of the branches. All the above is in full agreement with the conclusions made by G. S. Starostin (G. Starostin 2009; 2015: 361).

Notably, the geographically central pair, Yeniseian-Burushaski, takes an extreme rather than a central position on the graph. The reason is its connection with the Eurasiatic macrofamily, maybe specifically with Altaic (the most isolated Eurasiatic branch). As to possible connections between DCM and Eurasiatic, we note that Yeniseian and Altaic are neighbors in the graph: "collaterals" may indicate early areal contacts between the common ancestor of Yeniseian and Burushaski, on the one hand, and proto-Altaic on the other.7 Indeed, of all the non-DC branches, the Altaic shows the highest share of lexical matches with Yeniseian and Burushaski – 3.6%. Small as it is (two words from the 50-word list at most), geographic consideration prevent us from ignoring it.

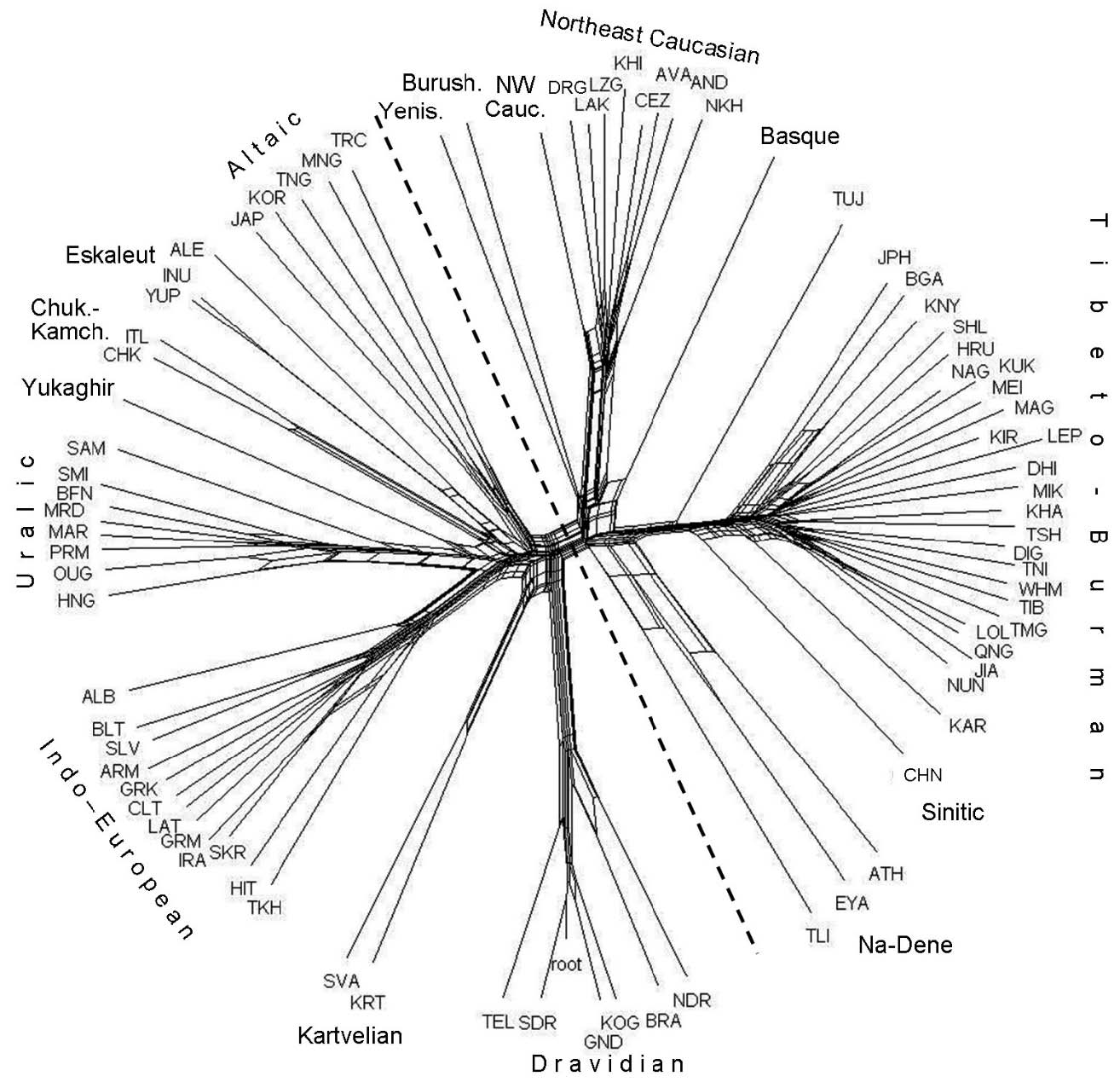

The network of separate languages (Fig. 4) helps to specify and correct the reconstructed pattern. It shows that both genetic and areal ties link the common ancestor of Yeniseian and Burushaski with proto-West Caucasian whereas East Caucasian languages are closest to Basque. Areal contacts between Basque and proto-Nakh are especially evident. Here too, as in the network of families (Fig. 3), the Burushaski–Yeniseian clade adjoins the Altaic branch and is connected with it by "collaterals."

The most isolated branch of Sino-Tibetan is not Chinese but Tujia, which again agrees with G. Starostin's finding (http://starling.rinet.ru/new100/eurasia_long.jpg).8 This supports the view that Sinitic is not opposed to Tibeto-Burman, but is part of it (see, e.g., van Driem 1998; Blench and Post 2014; Sagart et al. 2019). However, the idea that Sino-Tibetan is a sister branch of Na-Dene (Bengtson and Starostin 2011), which appeared compatible both with the two-dimensional configuration of separate languages (Fig. 2) and with the topology of the generalized tree (Fig. 3), is not upheld by this analysis. Three Na-Dene languages appear a separate group whose common origin is problematic and whose members are linked by strong areal ties. In other words, it may be a Sprachbund rather than a clade. This idea has already been voiced (Krauss 1976: 341). Within Sino-Tibetan, the Naga branch (of the Kuki-Chin-Naga group) is very short, as in G. Starostin's tree, which may indicate low evolutionary rate. This, in turn, suggests that an unusually high number of ties linking Naga with other languages (Fig. 2) may be due to the retention of a larger share of ancestral lexicon.

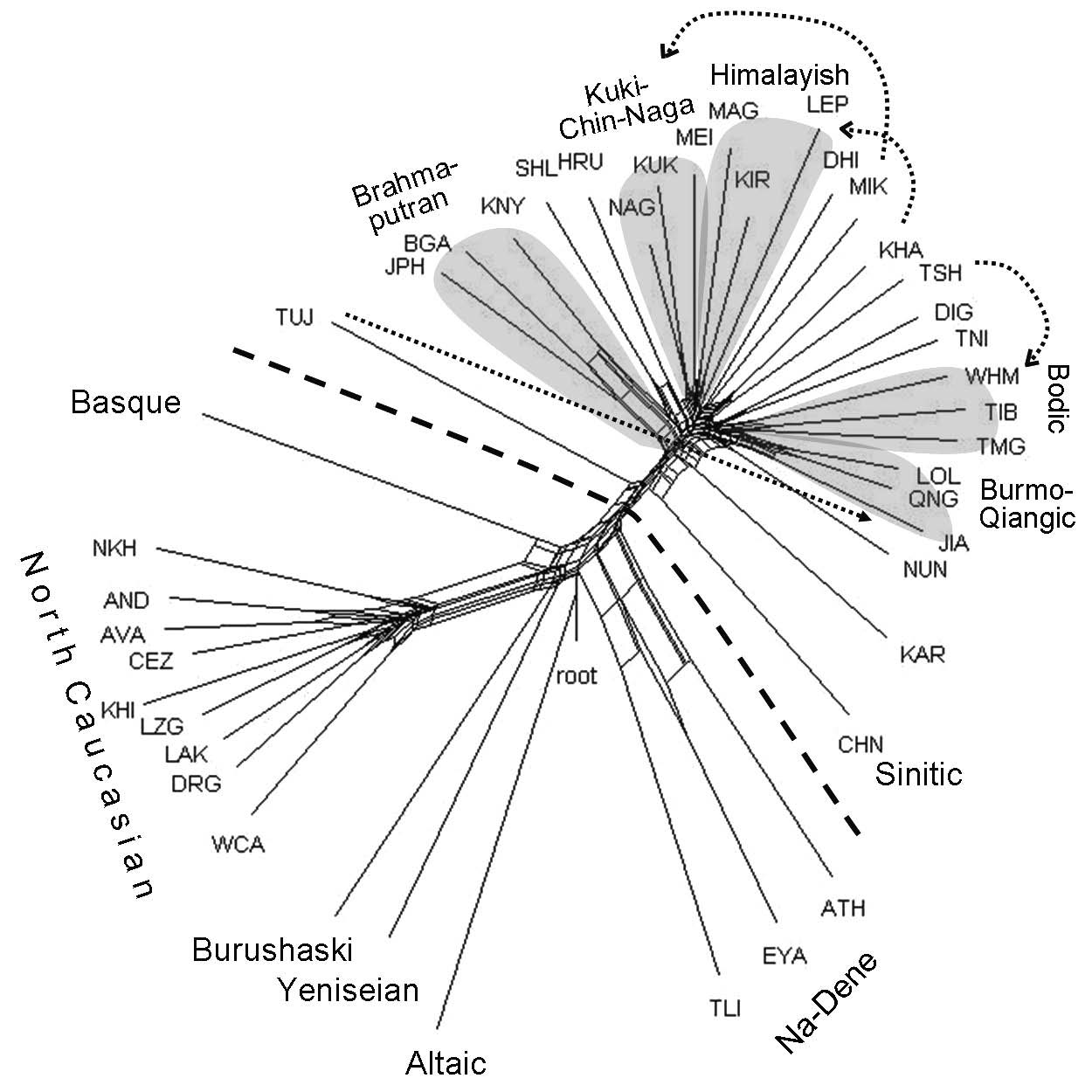

The close view of the same classification is presented by the network of DC languages, rooted by Altaic9 (Fig. 5). The Sino-Tibetan classification shows certain correspondences with that in the electronic catalog "Glottolog" (https://glottolog.org/). Specifically, five families, consisting of three branches each, are supported. Certain discrepancies are observed too: Tujia, which is attributed to the Burmo-Qiangic branch in "Glottolog," is quite distant from it in the network and is generally remote from others; Mikir is separated from the Kuki-Chin-Naga group; Kham and Tshangla, which appear related in the network, are attributed to two branches, Himalayish and Bodic, respectively. Old Chinese, which is an early branch, like Tujia, is less isolated, being connected with Tibeto-Burman branches, specifically Karen, by collaterals.

In sum, one can speak of three groups within DCM. The first includes Yeniseian, North Caucasian, Burushaski and Basque—the relationship between Yeniseian and Burushaski being the most evident (Fig. 1, groups II and V; Fig. 2, right part). The second group consists of the Sino-Tibetan family, which is the most isolated. The third group is Na-Dene (Figs. 3–5). Affinities between these three groups are not clear.

Homeland and Migrations

I will now focus on the highly contentious issue of the DC homeland. As the latter was hardly situated either in the westernmost or in the easternmost part of the modern distribution area of DC languages (Pyrenean and North American, respectively), basically three options remain. The first is the Near East; the second, East Asia; and the third, some intermediate territory such as Central Asia and/or South Siberia. The Near Eastern theory is advocated by comparativists of the Moscow school. G. S. Starostin (2015: 363–365) and A. S. Kassian (2010: 416–417, 428–432) mention two facts. First, the extreme complexity and, accordingly, archaism of North Caucasian phonology and morphology indirectly suggest that North Caucasian speakers had neither undertaken distant migrations nor maintained intense contacts with speakers of other languages. Second, the split of common DC, dating to mid-11th millennium BC by glottochronology, was followed by the transition to farming in the Near East, resulting in population growth, which triggered the spread of surplus population from that region. The most obvious implication was the introduction of languages spoken by early farmers to Europe via Anatolia. In the 7th millennium BC, according to A. S. Kassian, the paths of proto-Basques and proto-North Caucasians diverged in the Balkans,10 from whence the latter, having skirted the northern Black Sea coast, arrived in the Caucasus, where the event was marked by the 4th millennium BC Maikop culture (Kassian 2010: 427).11 Eastward migrations of other DC speakers, reconstructed by the Moscow comparativists, are purely speculative (Kassian 2010: 429–432).

A. A. Romanchuk (2019: 181–181; 2020), on the other hand, believes that the DC speakers migrated in the opposite direction: from eastern Eurasia westward. He draws mostly on genetic data à la G. van Driem's "Father Tongue Theory" and A. A. Klyosov's "DNA Genealogy," trying to establish connection between the spread of the Y-chromosome haplogroup R from Siberia westward and the migrations of DС speakers. He, admittedly, proclaims his disagreement with Klyosov's methods, arguing that the conclusion about the R1b subclade allegedly marking the DC speakers, made by them both, is a "sad coincidence" (Romanchuk 2019: 13; cf., Klyosov 2015: 131–136). This reservation is unnecessary: a cursory glance at the distribution map of R1b (Klyosov 2015: 137) suffices to note its general disagreement with the geography of language families. What one can discern at best are partial correspondences. But Klyosov's "Arbins," marked by R1b and viewed as a people, are as fictitious as his "Aryans" (those marked by R1a).

Romanchuk's observation that the westward migration from Siberia, marked by the ANE (Ancient North Eurasian) autosomal component (Romanchuk 2019: 166–167; 2020), deserves greater attention. Genome-wide components are more informative for tracing migrations than are haplogroups, and it is not incidental that their names, unlike those of haplogroups, refer to geography. What we deal with in this case, too, are not "peoples," of course. Because the reconstructed stages are very ancient, we can expect only partial coincidences with linguistic facts. The ANE component was first described in an Upper Paleolithic boy from Malta near Irkutsk, dating to 24 thousand years before present (BP), and then in a male and a girl from Afontova Gora II near Krasnoyarsk, dating to 15–17 thousand years BP (Raghavan et al. 2013; Fu et al. 2016). Its share is very high in Kets as well as in Selkups, Chukchee, Koryaks, and American Indians. Among the ancient groups, those closest to Kets in this respect are Early Bronze Age Okunev people and Late Bronze Age Karasuk people (Flegontov et al. 2016). Kets may have inherited ANE from any or both of those populations in their Altai-Sayan homeland (ibid.).

ANE spread from Southern Siberia in two directions: westward to Eastern Europe and the Caucasus, and eastward to the New World where it is very frequent in American Indians (ibid.). In Eastern Europe ANE became the principal constituent of the EHG (Eastern Hunter-Gatherer) component, and in the Caucasus (Georgia) it appeared in the late Upper Paleolithic, between 26 thousand years BP (Dzudzuana, where it is absent) and 13–14 thousand years BP (Satsurblia, where it is present, as in the Mesolithic sample from Kotias Klde, Georgia, dating to 12–10 thousand years BP, and in the 8th millennium BC Neolithic sample from Ganj-Dareh in northern Iran (Lazaridis et al. 2018; Jones et al. 2015). In the Caucasus, ANE became part of the CHG (Caucasus Hunter-Gatherers) component, the principal marker of the Yamnaya expansion into Europe. Interestingly, the high content of ANE links Kets with populations of southwestern Central Asia and the Northern Caucasus (see map in Wesolowski 2015). One of the Trans-Beringian migration waves introduced this component to the New World, and one of the migrant populations was the proto-Na-Dene.

Who, then, carried proto-Basque to the Pyrenean peninsula? Clearly, not populations marked by ANE, which was absent in Western Europe before the Yamnaya (i.e., Indo-European) expansion. Theoretically, languages related to Basque could have been introduced to Europe with the autosomal component AF (Anatolian Farmers) in the process of Neolithization. However, being common in Anatolia and partly in the Caucasus, AF was quite rare in the steppe and in Southwestern Central Asia (Damgaard et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2019), consequently, its connection with DC speakers was secondary. Recently, a notable fact was discovered: AF resulted from the admixture of two components, one autochthonous, typical of the pre-agricultural population of Anatolia, the other introduced by a migration from Iran approximately in the 11th millennium BC (Chintalapati et al. 2022). This estimate coincides with the split of proto-DC, as estimated by glottochronology.

The general correspondence between genetic and linguistic facts is indistinct. The situation with the Eurasiatic macrofamily is similar. The same disagreement is observed even at a much lower taxonomic level, as in the case of Turkic peoples and languages.

The same applies to the Burushaski-Yeniseian clade. Although according to glottochronology, these languages diverged in mid-7th millennium BC (G. Starostin's unpublished data, cited by Kassian 2010: 424), their relationship is still apparent (Figs. 1–5).12 Certain facts suggest that the ancestors of Yeniseians had migrated northward from the Altai-Sayan highland during the Karasuk era (Chlenova 1969). This is confirmed by genetic data, demonstrating that the population closest to Kets are the Karasuk people (Flegontov et al. 2016). V. Blažek (2017) has found presumably Yeniseian toponyms in the steppes of Kazakhstan and Southwestern Central Asia. G. van Driem believes that a macro-Yeniseian language ancestral to Burushaski had been introduced to the Himalayas by a group related to the Karasuk people (van Driem 2001: 1201–1206).

However, this could have happened much earlier, as demonstrated by petroglyphic masks of the Okunev type in Kashmir and Ladakh (Jettmar 1985; Devlet 1997; Sokolova 2012). Because no such petroglyphs were found in Southwestern Central Asia, whereas Early Bronze Age cultures of Xinjiang display Okunev parallels, this artistic style was apparently introduced to the Himalayas not from the north but from the east (Bruneau and Bellezza 2013). According to Y. E. Berezkin, Okunev petroglyphic masks "doubtlessly belong to the imagery typical of the pre-Yin cultures of China" (Vasiliev et al. 2015: 469). To this one should add parallels between Okunev petroglyphs and those of the Angara, and between Okunev ceramics and the Neolithic pottery of the Baikal area and even the Late Pleistocene pottery of the Amur (Sokolova 2007). From East Asia, the iconographic tradition related to the Okunev style was introduced to the natives of the Northwest coast of North America, specifically to Eskimos and Tlingit, and eventually further south to Indians of Mesoamerica and the Andes (Vasiliev et al. 2015: 489–538). In Western Eurasia, no such parallels are known.13

Judging by the Y-chromosome haplogroups, the Yeniseian-Burushaski linguistic relationship was established without biological admixture: the Burusho evidently speak a borrowed language. Genetically, they are unrelated to Kets and resemble their Pakistani neighbors (Qamar et al. 2002). As concerns the genetics and physical type of Yeniseians themselves, their well-known "southern" ties do not reach further than the Altai-Sayan highland. The genetic resemblance between Kets and the Okunev population is quite distinct (Flegontov et al. 2016). Cranial studies suggest that Okunev people can be described as "collateral relatives" of Native Americans (Kozintsev et al. 1999; see Kozintsev 2004, 2020b, 2021b, for references to genetic studies upholding our finding). At the genome-wide level, the connection manifests itself in the high content of the ANE component. These facts suggest that the Okunev people may be tentatively regarded as the ancestors of Yeniseians and, at the same time, "collateral relatives" of Na-Dene, in parallel with E. Vajda's hypothesis (Vajda 2010). G. Starostin's lexicostatistical data admittedly do not support this (see above), so a more moderate (and, in my view, quite plausible) proposal would be that Okunevans spoke one of DC languages (Kozintsev 2023). This idea is upheld by Eastern Siberian, Far Eastern, and Chinese parallels to Okunev culture, suggesting that these people could be collaterally related to Sino-Tibetans as well. Indeed, lexicostatistical data indicate a relationship between Sino-Tibetan and Na-Dene (Starostin G. 2015: 361 and his unpublished data at https://starlingdb.org/new100/eurasia_short.jpg; see Figs. 2 and 3). Maybe the language spoken by Okunev people was a link between both? This question appears incompatible with the fact that the split of proto-DC occurred in the 11th millennium BC whereas Okunevans lived in the late third–early second millennium BC and therefore could have spoken only one of the filial DC languages. The contradiction, however, arises only under the strictly genealogical model. Networks, which make allowance for areal ties (Figs. 4 and 5), demonstrate that this model is inadequate because contacts between filial branches could have persisted for a long time after their divergence.

Because, for chronological reasons, Okunevans could take part neither in the peopling of the New World nor in the proto-Sino-Tibetan migration to China (see below), they must be regarded as a relic group, which survived for several millennia in places from whence their ancestors had migrated in various directions. As to the Karasuk people, they might be related only to Yeniseians. A similar suggestion with regard to Xiongnu received no support (Savelyev and Jeong 2020).

Interestingly, the content of ANE is high in a population associated with so-called Steppe Maikop (Wang et al. 2019). Genetically it has little in common with Maikop proper, but displays ties with the Botai population of Northern Kazakhstan and Western Siberia, sometimes considered ancestral to Okunev (Jeong et al. 2019). This means that migrants from the east borrowed elements of the Maikop culture without hybridizing with the local population.

If, as I tried to demonstrate, the Maikop people were late proto-Indo-Europeans (Kozintsev 2018, 2019a,b), could the Steppe Maikop people have spoken proto-North Caucasian? There are indications that North Caucasian dialects were spoken by people associated with two cultures, Novosvobodnaya (possible ancestors of Northwest Caucasians) and Kura-Araxes, or Early Transcaucasian (likely ancestors of Northeast Caucasians and possibly of Hurro-Urartians) (Kozintsev 2019a,b; Kassian 2010: 423). Steppe Maikop could hardly be ancestral to any of them. Could it be associated with proto-Kartvelians? Or with people speaking a DC language that eventually went extinct? These questions cannot be answered. The only thing one can say is that in this case, too, the migration was directed from the east to the west. Migrations in the opposite direction began later, only in the Yamnaya-Afanasievo age, and they were definitely related to the spread of Indo-European languages (Kozintsev 2021b).

I will finally touch upon certain geographic patterns in the distribution of DC languages that are relevant to the homeland issue. We note a number of parallels with the spread of Eurasiatic languages (Kozintsev 2020a). The reason is that the distribution areas of both macrofamilies largely overlap, and in both cases it is reasonable to assume that the source of migrations (or of demic diffusion or even of language spread alone) was situated neither in the westernmost nor in the easternmost parts of the area but in its central part. Such an assumption makes it easier to interpret parallels between languages vastly separated from one another, such as Indo-European and Eskaleut in the case of Eurasiatic, or Basque and Sino-Tibetan in the case of DCM (Fig. 1).

Discussing the ANE component, I have pointed to South Siberia, but this idea is based solely on the earliest find: Malta. In the case of Eurasiatic languages, certain considerations, admittedly indirect, suggest that the homeland was located either in the Trans-Caspian or, more likely, in Southeastern Kazakhstan or Zhetysu (Kozintsev 2020a). But wherever the presumed center is placed, the route of one of the filial branches (Indo-European in the case of Eurasiatic; North Caucasian-Basque in the case of DC) passed in the east-to-west direction: across Kazakhstan, Southwestern Central Asia, and northern Iran to the Caucasus, from there to Anatolia and, in the case of DC, further west, to Western Europe. The fact that the ANE component spread also along the northern route, across Western Siberia to Eastern Europe, suggests that some part of the pre-Indo-European and pre-Uralian population of those regions might have spoken now extinct DC languages.

Another direction is northward, down the great Siberian rivers: the Irtysh, the Ob, and the Yenisei. These were the routes whereby Uralians and Yeniseians arrived in the taiga zone. The third route passed in the northeastern direction, down the Lena and toward Beringia. In the case of Eurasiatic speakers, this was the route taken by proto-Yukaghirs, proto-Eskaleuts, and proto-Chukotko-Kamchatkans; in the case of DC speakers, by those who spoke proto-Na-Dene.

The fourth direction was eastward, along the corridor between the Tien Shan and the Mongolian Altai to Northern China. Among the Eurasiatic populations, this route was chosen by ancestors of the Altaic speakers. Among those speaking DС languages, proto-Sino-Tibetans migrated along the same path. Eventually both secondary homelands became close both in time and in space: the Altaic (or Transeurasian, as M. Robbeets calls it) homeland was likely situated in southern Manchuria in the 7th–4th millennia BC (Robbeets 2017), and the Sino-Tibetan homeland somewhat further south, in the middle Yellow River basin in the 6th–5th millennia BC (Sagart et al. 2019; Zhang et al. 2019).

Conclusion

What are the implications of all that? In the view of G. Starostin (2015: 366), while the age of both macrofamilies, Eurasiatic, or Narrow Nostratic, as he calls it, and DCM, is quite comparable, the latter's expansion began earlier, possibly much earlier, which accounts for the patchy distribution pattern of DC languages. However, the most apparent, if not the only fact indicating an earlier spread of DC languages, is the Na-Dene migration. But the relative chronology of the arrival of, say, proto-Sino-Tibetan and proto-Altaic/Transeurasian in China is not known (see above), and it is not at all certain that the early appearance of the ANE component in the Caucasus suggests that DC languages appeared there likewise early or at least earlier than proto-Indo-European (Kozintsev 2019a,b). "Avalanche-like" migrations such as Andronovo (apparently Indo-Iranian) or the spread of Turkic languages across Eurasia, like a less impressive but still intense Uralization of the forest belt of Western Siberia and Eastern Europe are relatively recent events unrelated to the initial spread of Eurasiatic. These events may account for the patchy distribution of many DC languages.

As concerns the initial stages of the spread of Eurasiatic and DC languages, their relative chronology is unknown; moreover, their migration routes could be the same. Wasn't this parallelism caused by a deep relationship between the two macrofamilies and by their interlinked histories?

Notes

1 My sincere thanks go to G. S. Starostin, A. S. Kassian, and M. A. Zhivlov for granting me access to their matrix of pairwise lexical matches between languages according to 50-word lists. I thank J. D. Bengtson, Y. E. Berezkin, and V. V. Napolskikh for useful comments and criticism. Correspondence may be addressed to [email protected] ↩

2 The model was implemented with the SplitsTree4 package written by D. Huson and D. Bryant (https://software-ab.informatik.uni-tuebingen.de/download/splitstree4/welcome.html). ↩

3 The model was implemented with the PAST package written by Ø. Hammer (https://folk.uio.no/ohammer/past/). ↩

4 The problem does not arise when the quasi-areal model is used. ↩

5 The choice of Dravidian as a root was motivated by the fact that unlike Kartvelian, which may have had areal and possibly genetic ties with Indo-European, Dravidian appears to be the most isolated family. ↩

6 The fact that proto-DC is represented by a band of several edges does not contradict monophyly because the band is narrow and the edges are parallel (see Nichols and Warnow 2008: 812). ↩

7 Unlike a usual tree, where the order of branches within clusters is arbitrary, network branches are arranged in a definite order, which mirrors possible areal ties between them. ↩

8 Usually Tujia is considered a separate branch of Sino-Tibetan (see, e.g., Matisoff 2003: 164, 188, 694; Blench and Post 2014). In the electronic catalog "Glottolog" it is attributed to the Burmano-Qiangic branch (see below). According to Y-chromosome data, ancestors of Tujia could be related to Di-Qiangic tribes; in addition, they are genetic relatives of the Chinese (Xie et al. 2004). This is confirmed by the study of leukocyte antigens system HLA (Zhang et al. 2012). ↩

9 Altaic was chosen because other non-DC branches were not included in this analysis. The study of early ties between DC and Altaic might prove of interest in the future (see below). The lesser age of Altaic compared to DCM is irrelevant in this case. The substitution of Dravidian by Altaic had little effect on the topology of the network. ↩

10 In his view, connection with the Balkans (specifically with the 5th millennium BC Balkano-Carpathic metallurgical center) is evidenced by an unusually large number of words for metals in proto-North Caucasian (Kassian 2010: 425). ↩

11 While this scenario does not appear plausible in general, there is a grain of truth in it. The Novosvobodnaya culture (which Kassian erroneously considers as but a late stage of Maikop) can indeed be associated with proto-Northwest Caucasians. But Maikop proper, definitely southern by origin, can apparently be attributed to late proto-Indo-Europeans (Kozintsev 2019a,b). ↩

12 A. S. Kassian (2010: 430) believes that this group includes also proto-Hurro-Urartian and Hattic. ↩

13 Certain publications refer to an Okunev petroglyphic mask allegedly discovered in the Gegam Mountains, Armenia. To all appearances, this reference is erroneous. ↩