In Memoriam

Memories of Vladimir Antonovič Dybo (1931–2023)

Vladimir Antonovič Dybo died at the impressive age of 92 years old on May 7, 2023. Since his academic career has already been well-described,1 I will mainly concentrate on his younger years and on his ancestry. I would also like to add several personal memories of this exceptional man.

Vladimir A. Dybo was born on April 30, 1931 in the village of Pyrohivka (Пирогівка = Russian Пироговка) on the Desna River in the Sumskaja Region in the northernmost part of Ukraine. His father, Anton Timofeevič Dybo, was an employee of the railroad system, and during the Russian Civil War worked as an anti-communist political activist. Vladimir Dybo's ancestors in his father's line were Cossacks from Zaporižžja. His maternal grandmother originated from the Cossack community in the region of the Don, and his maternal grandfather was Polish.

When Vladimir Dybo was one-year-old, his family left Ukraine and moved from one small city to another. Dybo finished high school in the city of Pavlovo in the Region of Nižnegorodskaja, approximately 80 km from Nižnyj Novgorod (then called Gorkij). In 1949 he begun to study philology at the State University of Gorkij, but he was so disappointed by the dogmatic application of Marrism2 in linguistics there that he seriously considered changing his major to physics. Fortunately, in 1950, Marrism was rejected by Stalin himself (thanks to the arguments of another Georgian, Arno Čikobava), and a standard linguistics curriculum could again be taught in the Soviet Union.

Dybo graduated from the Department of Russian language and Literature of the Faculty of History and Philology of the State University of Gorkij in 1954. He then found employment as a teacher of Russian language and literature at a school for working youth in the city of Krasnogorsk, in the Zvenigovskij District of the Mari Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. For him it was a welcome opportunity to learn the Mari and Mordva languages.

During that period he independently recognized a relationship between the Indo-European and Uralic languages, though he was not yet familiar with the Nostratic hypothesis. Even in the remote region of Krasnogorsk, thanks to an inter-library service, Vladimir Dybo could study the most recent publications in the field of comparative linguistics. He became very interested in the laryngeal theory, which by then had been formulated by scholars in several different versions and applied to the Indo-European protolanguage.

Because he did not personally know anyone with whom he could discuss these subjects, he eventually wrote a letter describing his observations to Vjačeslav Vsevolodovič Ivanov3 in Moscow, a new authority in the field of linguistics as it had been resuscitated after the fall of Marrism. After their intensive correspondence V.V. Ivanov invited Dybo to enroll in a postgraduate program at the Department of Common and Comparative Linguistics of the Faculty of Philology of Moscow State University in 1955.

In 1958 he was employed at the Institute for Slavic Studies of the USSR Academy of Sciences. In this position he was joined by his younger colleague, the slavicist Vladislav Markovič Illič-Svityč, who was also a native of Ukraine (born in Kyev, Sept 12, 1934). In his paternal line, Illič-Svityč was the descendant of Polish aristocracy, and of Polish Jewish intellectuals in the maternal line.

Dybo's wife Valeria Čurganova (1931-1998) was also a linguist. When their daughter Anna Dybo was born in 1959, it became necessary to solve the critical problem of finding housing for the growing family. Since neither were residents of Moscow, and lacking any support from the Communist Party, they could not get a flat anywhere in the capital. Consequently, Vladimir Dybo and his friend Vladislav Illič-Svityč became members of the Flat-building cooperative (Жилищно-строительный кооператив) newly introduced by Nikita Xruščev in the USSR. They began to build their individual flats in the satellite city of Mytišči, situated about 20 km from Moscow.

By then the two were already close collaborators, their common focus being Slavic and Baltic accentology. Vladimir A. Dybo defended his Ph.D. thesis 'The problem of correlation of two Balto-Slavic series of accentual correspondences in a verb'4 on May 10, 1962. Vladislav M. Illič-Svityč published his first monograph Именная акцентуация в балтийском и славянском. Судьба акцентуационных парадигм in 1963.5 This monograph developed into the dissertation that he defended in January 1964, which was then published in 1979 under the English translation, 'Nominal Accentuation in Baltic and Slavic.'6

Already in 1961 Dybo had published one brilliant study, explaining the phenomenon of the shortening of expected long vowels in Germanic, Celtic and Italic in a wider context of Indo-European accentology. Illič-Svityč (1962) supported his solution, offering some small modifications. Vladimir A. Dybo and Vladislav M. Illič-Svityč became co-founders of the modern Moscow accentological school. It is important to stress that their results became known in the West especially thanks to Frederik Kortlandt (1975).

In the first half of the 1960's Illič-Svityč drew his attention to the so-called Nostratic hypothesis, first intuitively formulated (and named) in 1903 by the Danish scholar Holger Pedersen. Illič-Svityč was convinced that there existed a distant genetic relationship between six language families of the Old World: Afroasiatic, Kartvelian, Indo-European, Uralic, Dravidian and Altaic. Today Afroasiatic and Altaic would be considered macrofamilies.

In order to reconstruct the common protolanguage of these six language families, he applied the classical comparative method. This involved the formulation of regular phonetic correspondences between the already reconstructed daughter protolanguages. His larger ambition was to reconstruct the Nostratic protolanguage, not only in its phonetic inventory but also in its morphology and lexicon. Illič-Svityč began mapping the phonetic correspondences between the languages and, in parallel, collecting the lexical comparanda and formulating Proto-Nostratic reconstructions. On all important questions he consulted with his colleague and neighbor Vladimir Dybo. After 1964 these consultations also included a new member of the Nostratic club, the (originally) romanist, Aaron Borisovič Dolgopoľskij7.

When Vladislav M. Illič-Svityč tragically died on August 22, 1966, he was not yet 32 years old and was several months short of finishing the construction of his flat in Mytišči. He had more or less completed his formulations of the phonetic correspondences between the reconstructed daughter protolanguages and a determination of the Proto-Nostratic phonetic inventory (Illič-Svityč 1968). These were established on the basis of more than 600 lexical correspondences, as those were described in an article published posthumously in a very abbreviated form (Illič-Svityč 1967).

After the death of Illič-Svityč, Vladimir Dybo dropped his accentological research and decided to finish Nostratic Comparative Dictionary, the magnum opus of his deceased friend. Over the course of five years, based on data from within a partial manuscript listing a number of individual entries, and from vast comparative material found in numerous files, Dybo was able to prepare the first volume (Illič-Svityč 1971) for publication. This consisted of an introduction and a listing of 245 reconstructed Nostratic lexemes or morphemes with full documentation and references. As far as I know, the physical publication of this first volume of the Nostratic Comparative Dictionary was possible only thanks to the significant financial support of Vladimir Dybo himself from his personal family budget.

Having closely colaborated with Illič-Svityč when he was preparing the manuscript of his Nostratic Dictionary, Vladimir Dybo had the full right to be an acknowledged co-author of this monograph. With one exception where he reveals his authorship (the tables of phonetic correspondences on pp. 146-171), he remains hidden under the designation redactor.

The second volume, published five years later (Illič-Svityč 1976), consists of 108 new entries that were prepared by Illič-Svityč. Some of them were more or less in a definitive form, others only in the form of notes. Although the main editorial work was made again by Vladimir Dybo, now he could cooperate with other colleagues. First among these was Aaron Dolgopolsky, who had originally collaborated with Illič-Svityč himself.

After the death of Illič-Svityč, Vladimir Dybo and Aaron Dolgopolsky founded an informal discussion group called the Nostratic Seminar. There they presented ideas related to distant relationships between language families and discussed the possibilities of applying the classical comparative method to such research. Over the span of several years the Nostratic Seminar became very popular and generated a new direction in comparative linguistics called the Moscow school of comparative linguistics. Among this group appear representatives of a younger generation including: Evgenij Xelimskij (Eugene Helimski), Sergej Starostin, Alexander Militarev, Olga Stolbova, Viktor Porxomovskij, Vladimir Orel, Ilja Pejros, Oleg Mudrak, Anna Dybo, Jakov Testelec and many others. Most of them cooperated with Vladimir Dybo on the preparation of the second volume (Illič-Svityč 1976), and especially the third volume (Illič-Svityč 1984), which proposed 25 new Nostratic lexemes reconstructed on the basis of the notes and files of Illič-Svityč.

Meanwhile, one important change occurred: In 1976 Aaron Dolgopolsky legally emigrated from the USSR to Israel. But thanks to the efforts of Vladimir A. Dybo8 the Nostratic Seminar would continue to persue its main subject of interest: the discovery of the details concerning the distant relationships among language families. This investigation became supported thanks to a diplomatic masterpiece acheived by Vjačeslav V. Ivanov, who convinced the academic and political organs that without this study it was impossible to develop a system of artificial intellegence. The seminar continued (and continues up to the present time, now under a leadership of Mixail Živlov), most frequently meeting in the flats of its members. The reason for this was that academic institutions had to be closed at 9:00 PM, but participants of the seminar at that time were frequently in the middle of very vigorous discussions, and they did not want to stop early.

In March, 1985, I visited Moscow for the first time, as a member of an organized group of tourists. Already by that time I had been in correspondence with Alexander Militarev. I informed him about my visit and he invited me for a personal meeting with him and Sergej Starostin in the building of the Oriental Institute where they both were employed at that time. It was a short, but very hearty meeting, and it turned out to be the prelude to another much more important meeting: For later that evening Alexander and Sergej invited me and my wife to participate in the Nostratic Seminar.

At that time the meetings were held in the flat of Anna Dybo, the daughter of Vladimir Dybo, and her then husband, Sergej Krylov. It should be noted that Anna and Sergej, although divorced a long time ago, still actively colaborate in matters of comparative linguistics. I still remember quite clearly that Sergej Starostin gave a lecture that evening about one sub-group of the Sino-Tibetan languages (Khaling?). Also attending were: Alexander Militarev, Evgenij Xelimskij (Eugene Helimski), Ilja Pejros, Olga Stolbova, Sergej Nikolaev, Oleg Mudrak, and, naturally the pair of hosts, Anna Dybo and Sergej Krylov.

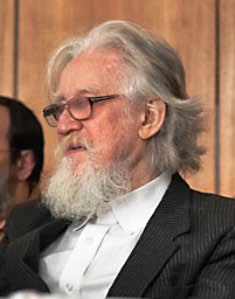

Among all the others was the founder of the Nostratic Seminar, Anna's father, Vladimir A. Dybo. Although he was only 54 in 1985, he had the look of a biblical patriarch: long white hair and a long white beard, somewhat resembling the novelist Lev Nikolaevič Tolstoj.

I subsequently saw Vladimir Dybo during one accentological conference9 held in Opava (Czech Republic) in 2009. But the last time we met was during a conference (held via Zoom10) that was organized to celebrate his 90th birthday (April 2021) where his appearance was exactly the same. In the second half of the 1980's, when the process of thawing in the Cold War increased, I had an occasion to visit Moscow every year during the period 1985-1990. I had met with Vladimir Dybo every year during that time.

But for me the most important meeting was realized during the conference11 organized by Vitaly Shevoroshkin, a former student of Vladimir Dybo, at Michigan University at Ann Arbor in November 1988. The reason for this was that Vladimir Dybo gave me the first volume of the Nostratic Comparative Dictionary (Illič-Svityč 1971). This volume was absolutly unavailable, unlike the following volumes, which I had a chance to buy in Moscow in 1985 or later. Naturally, without the first volume it was impossible to work in the field of distant relationships of language families. My solution was that in 1973 I borrowed the book from the University Library in Prague and rewrote the whole comparative lexicon, approximately 200 pages, by hand into a big excercise book. The hand-written copy of the second volume followed in 1977. It was in this form that I used the second volume up until 1985 and the first volume even until 1988, when I could finally replace them with the published books.

When Anna Dybo divorced, she returned to her father's home in Mytišči. She invited me for a dinner two or three times (2000, 2004, 2008?). It was always a good occasion for linguistic discussion not only with her, but also with her father, Vladimir A. Dybo, on the place with its genius loci, where the Nostratic hypothesis was resuscitated and had evolved into a regular scientific discipline.

Authorised by Anna Dybo on Aug 26, 2023

1 <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vladimir_Dybo>. ↩

2 https://www.sas.upenn.edu/~haroldfs/540/handouts/ussr/marrist.htm ↩

3 See Blažek 2018. ↩

4 Проблема соотношения двух балто-славянских рядов акцентных соответствий в глаголе. ↩

5 Moskva: Izdateľstvo Akademii nauk SSSR, 1963. ↩

6 Translated by R. L. Leed and R. F. Feldstein. Cambridge (MA.) – London: MIT Press, 1979. ↩

7 See Blažek 2009. Hereinafter, only the form Dolgopolsky will be used. ↩

8 It should be mentioned that Vladimir Dybo, although apolitical, had some sins from the point of view of the Communist party of the USSR: he openly supported dissidents or expressed his protest against the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia in August 1968. ↩

9 The Fifth International Workshop on Balto-Slavic Accentology. ↩

10 Simpozium „Balto-slavjanskaja komparatistika. Akcentologija. Daľnee rodstvo jazykov", posvjaščennyj 90-letnemu jubileju akademika RAN Vladimiru Antonoviču Dybo (Apr 27-28, 2021). ↩

11 First International Interdisciplinary Symposium on Language and Prehistory (Nov 8-12, 1988). ↩

References

Václav Blažek

Department of Linguistics and Baltic Studies

Masaryk University

<[email protected]>